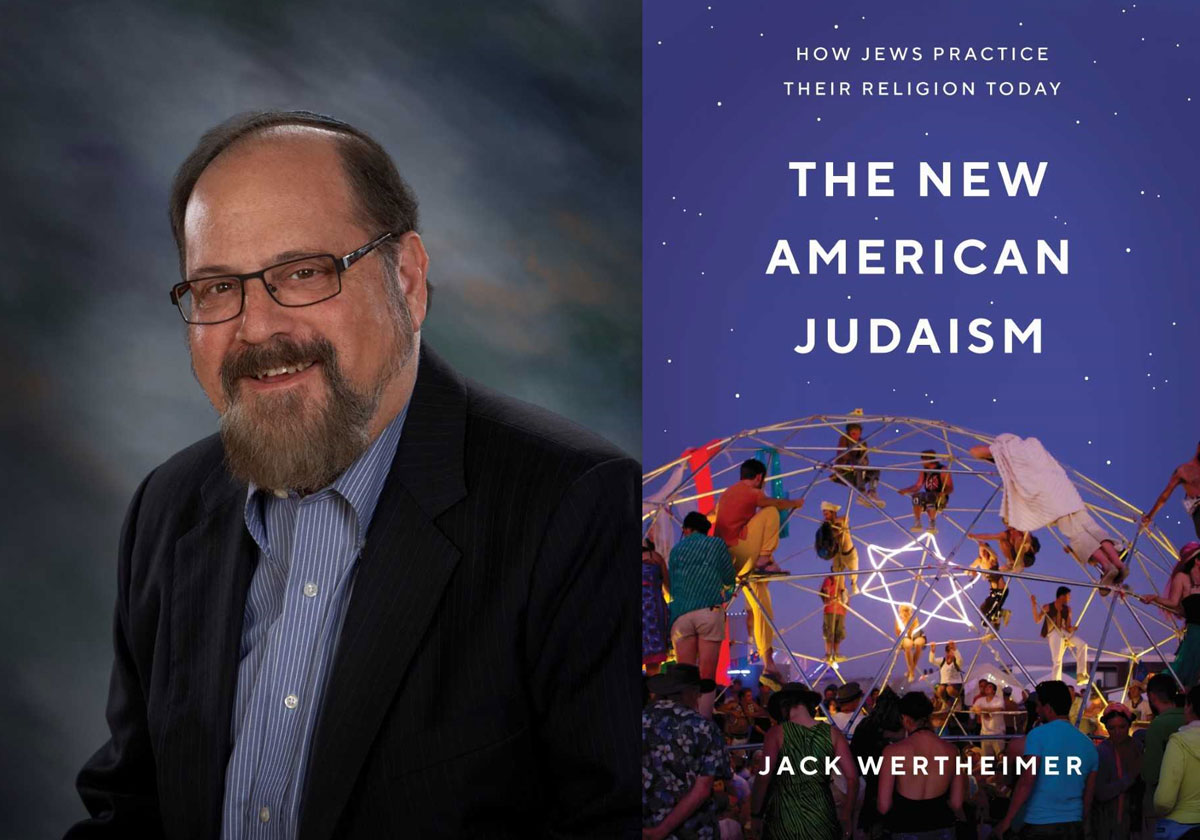

American Jewry is balkanized, divided into denominations ranging from the Haredi, who scrupulously and meticulously strive to obey both the Torah and oral laws, at one extreme, and Reform Judaism, whose roots lie in the rejection of Torah as divine word and rabbinic dicta on the other. Jack Wertheimer, in his newest book The New American Judaism, thoughtfully examines the full spectrum of Jewish practice, detailing the findings of recent independent surveys, disclosing the intimate thoughts of practicing rabbis, and analyzing the various movements’ successes and failures, as well as offering a comprehensive review of emerging non-traditional forms of Jewish worship.

We find that some Protestant denominations and conservative branches of Catholicism maintain a steady membership and in times of national crisis experience spikes in religious attendance. Yet, America, according to recent studies, is by-and-large continuing its decades-long decline in religiosity; Jews included.

Wertheimer notes that our liberties, unparalleled in Jewish history, can be portrayed as a storm eroding Judaism because they cultivate an environment encouraging Jews to move away from forms of Judaism fostered by Eastern European shtetel life, thereby allowing them to find their own religious expression outside of the synagogue. As a result, these freedoms are blamed for assimilation—the integration and acceptance of Jews into the wider secular world—resulting in such things as the loss of religiosity, rejection of traditional rabbinic leadership, and the swelling intermarriage rate.

Synagogues, whose mainstay typically consist of traditional Jewish families, recognize that survival depends on adaptation, including welcoming “others,” such as members of the gay and lesbian communities, singles, and intermarried couples, as well as expanding leadership roles to woman. Change also includes incorporating music; altering service lengths, times, and locations; reorganizing the sanctuary, and even offering multiple simultaneous services with differing modes of worship. But synagogue transformations are not equally acceptable to the elites and members of Jewish denominations as a whole, or even within a given denomination, leading to mixed messages for the rank-and-file. Some American Jews, particularly Millennials, have not waited for religious leaders to act, instead, they are self-organizing into alternative or temporary enclaves of unconventional Jewish practice and expression, including Orthodox outreach centers, the Reconstructionist movement, Jewish Renewal, and Havurot.

In The New American Judaism, Wertheimer wants to know if Jewish practices are a rejection of the synagogue, or merely a transition to a more individual form of spiritual expression, a type of DIY Judaism: Can Judaism survive without temples and all the personal and communal services they provide? He presents examples of current transdenominational efforts along with the question, Are denominations even needed anymore? Afterall, each denomination of Judaism believes in the same God, they basically differ on how to best to “serve”.

The inquiry for Wertheimer is not so much who is an American Jew, or even what is authentic Judaism, but rather how do American Jews identify with Judaism? To answer, he proposes a five-criteria measure, whose categories include “frequency of religious activity” and “preferred style of synagogue worship.” To the extent these groupings accurately quantify existing Jewish practice, synagogue leadership can address the very important strategic questions of where are we and where should we be?

The New American Judaism concludes with a description and analysis of the melding of two Jewish worlds—traditional and modern—in what Wertheimer calls “a new remix,” into a transdenominational Judaism. Yet, questions remain: how much accommodation turns into distortion? Can a transdenominational Judaism convey the religion’s distinctiveness? For how long can this counter-culture remain vibrant?

The New American Judaism is a captivating look at the institutions and believers making up the state of American Jewry, while offering unique insights into the problems and proposed solutions facing national leaders, pulpit rabbis, and declared Jews.

Republished from San Diego Jewish World