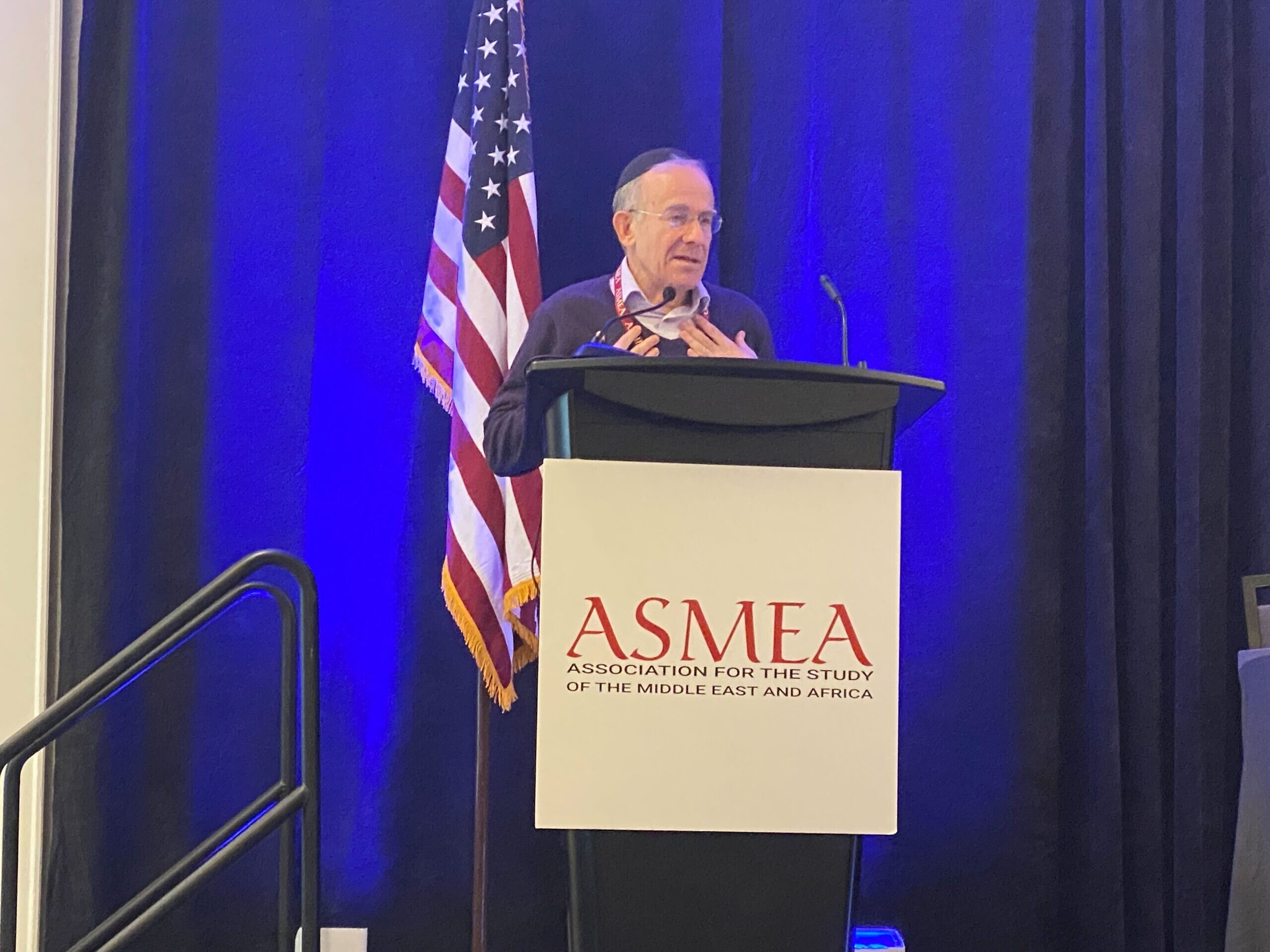

For attendees, the annual conference of the Association for the Study of the Middle East and Africa (ASMEA) represented a bulwark against the academic elitism and suppression of divergent ideas in their field. Coming together in a small but familial group of approximately 130 university professors and scholars from around the world—with more joining remotely due to lingering COVID-related travel restrictions and hesitation—ASMEA convened at the JW Marriott Georgetown in Washington from Saturday to Monday to again share ideas in-person.

The topics discussed in presentations of research during the conference varied in their level of controversy, but many of those in attendance often spoke about the treatment of their ideas and research in the academic field in their daily lives, with some openly admitting to being considered pariahs because they refuse to accept the orthodoxy that has dominated academic thought about the Middle East since the British Arabist scholars of the 20th century. The situation made worse by the troubling and growing ideological intolerance at research universities in the name of political correctness.

Another motivator for attendees at ASMEA was to avoid the politicization at other conferences that tend to espouse anti-Israel and anti-Western sentiments. The Middle East Studies Association (MESA) was often invoked with frustration by the scholars as one such example. MESA has strong support for the BDS movement. In May, after terrorist organizations in the Gaza Strip rained more than 4,000 rockets into civilian areas of Israel and were countered by a military response from Israel, MESA’s board issued a statement in support of the Palestinian people against the Israeli government, callings its actions apartheid but not mentioning the actions of groups like Hamas or the Palestinian Islamic Jihad in the 11-day conflict.

Asaf Romirowsky, ASMEA’s executive director, said that from its inception, ASMEA was created to counter MESA.

“If you had to categorize from a school of thought perspective, our association follows [Bernard] Lewis and [Fouad] Ajami, and people who follow MESA follow the Edward Said school of thought,” he said. “So there’s much more of a very strong, I would say, pro-Palestinian element, within the MESA narrative.”

Lewis, a British-born, Jewish professor of Middle Eastern studies at Princeton University and Ajami, a Lebanese-born professor and scholar at the Hoover Institution, co-founded ASMEA in 2007 to counter the anti-Israel and anti-American sentiments in MESA. Both were supporters of the 2001 war in Iraq.

The next year, they held their first conference, which grew to host up to 350 attendees prior to the coronavirus pandemic.

Most of the attendees at this conference were acolytes of Lewis and Ajami, and generally defined themselves as right-of-center ideologically. Zionism was freely discussed and not derided as racism.

Both of the late founders were honored at separate ceremonies. A panel was assembled at the start of the conference to speak about Ajami, which included his widow and his students. The next day, Lewis was honored by the establishment of an award and the selection of winners from submitted papers.

‘A candle of light in a dark place’

Still, few were willing to speak on the record with the media to criticize the academy or MESA—some fearing repercussions in their profession and others wanting to let their research speak for itself, rather than join the politicized rivalry between organizations and possibly reveal their bias.

“I have been attending ASMEA conferences for six years as a non-academic,” said one attendee who requested to remain anonymous. “ASMEA is the last stronghold of objective and productive Middle East academic research. ASMEA is holding up a candle of light in a very dark place.”

Romirowsky said it takes a lot of courage to stand up for a viewpoint and that many of the attendees had faced intolerance for expressing viewpoints that diverge from the orthodoxy.

“We want to give people the opportunity to share—share their ideas, share their work—and that’s what we’re here for,” he said. “We all support the exchange of ideas and free discourse of ideas. I think that it’s healthy for the academy to have much better balance, and I think that if we can provide another balanced perspective on the region, then we’re all for it.”

Topics included analyses of academic freedom, modern anti-Semitism, terrorism, foreign policy between Israel and its neighbors, as well as U.S. foreign policy in the Middle East and Africa. Some presenters also pointed to how anti-Israel bias and Arabism have for a long time infiltrated the foreign-policy wings of the American government.

On Saturday night, former Assistant Secretary of State for Near Eastern Affairs David Schenker spoke about U.S.-Lebanese relations.

“If the Biden administration decides that they’re not going to designate, they’re not going to sanction, they’re not going to go after Hezbollah in any way because they’re making a deal with Iran on the nuclear thing … that’s not going to help the region. It’s certainly not going to help the people we share values with in Lebanon,” replied Schenker, the Taube Senior Fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy when asked after his speech why American foreign policy so far has been ineffective in stopping Hezbollah despite massive investments in Lebanon.

The event’s keynote speaker during lunch on Sunday was exiled former Pakistan’s ambassador to the United States Husain Haqqani, who spoke in-depth about what he believes to be the coming of “Al-Qaeda 3.0” after America’s recent withdrawal from Afghanistan.

‘Important for national security’

Many of the scholars praised ASMEA for help in publishing their research, whether peer-reviewed journal material or books, complaining of challenges faced in doing so by traditional academic publishers at major universities whose academic boards, they said, were dominated by left-wing ideologues. They swapped stories of rejections and where they found the best publishers while they mingled or ate lunch.

One of the keynote speakers on the final day of the conference highlighted the problem.

Eliezer Tauber, a professor at Bar-Ilan University in Israel, mentioned the difficulties faced in getting his book about the 1948 Deir Yassin massacre published in the United States.

His book, The Massacre That Never Was: The Myth of Deir Yassin and the Creation of the Palestinian Refugee Problem, which included on-the-ground research pointing to no such massacre, is accepted by Israelis, Palestinians and scholars throughout the world, he said. What happened in the battle that led to the Irgun’s capture of the village in 1948, according to Tauber’s book, was embellished by Arab leaders at the time in order to compel neighboring countries to send armies and help the fledgling Palestinian Arabs.

While it was quickly published as Hebrew translation, it took years for it to appear in its original language, English.

He quoted some of the denial letters he received from publishers, including from top universities. While all agreed on the merits of Tauber’s research, most responded that the issue was simply too controversial.

“Everyone agreed on the book’s many strengths, [but] the consensus was that the book would only enflame the debate where positions have hardened,” one administrator wrote in a letter to Tauber.

For longtime attendee Christine Sixta-Rinehart, professor at University of South Carolina Palmetto College, the speeches by Schenker and Haqqani proved thought-provoking.

Sixta-Rinehart said more than some other academic societies, ASMEA cultivates firsthand knowledge of the areas it covers, encouraging scholars to learn about cultures and languages.

“There are many different points of view, and the scholarship has more depth. People have more understanding; they have more real-world experience with the topics and the countries. They’re language speakers. So I think the best way to say it is there’s a greater breadth and depth of knowledge by the presenters,” she said.

She said many of the speakers at the conference were area specialists, rather than quantitative international-relations experts who largely lack experience on the ground.

“Most of the area studies programs across the nation have been killed,” she explained. “So those of us who still do area studies believe in it because it’s important for national security—that you know the difference between a Sunni and a Shia, and that you know what a Kurd is and what it means to be part of Kurdistan. I think that we’re losing that. I think the area studies stuff needs to come back.”

ASMEA’s focus on the region has provided Sixta-Rinehart with the connections to conduct her own primary-source research.

“When I need somebody to help get me on the ground in Iraq or Israel or anywhere, I go to ASMEA because those contacts are there,” she said. “They know who the military people are there and the areas studies people. They’ve got diplomats coming and going. If I need something that’s real, I go to my contacts at ASMEA because they’ve always helped me. It’s actually pretty amazing what some of those people can pull off.”