This book came to me “over the transom,” that is, without any previous warning. Even though it is three years old, I’m glad that I had a chance to read and review it, as it clearly and unashamedly details another aspect of World War II and the Holocaust. It describes how Jewish refugees from Poland tried to avoid German Nazis and their Eastern European allies, and having no wish to become cannon fodder in the Soviet Army, instead drifted from place to place, gaming the Soviet system and stealing what was necessary to survive.

Yes, stealing, whether that be, in protagonist Yitzkhak Neiman’s case, meat, potatoes, water buckets, salt, or blankets.

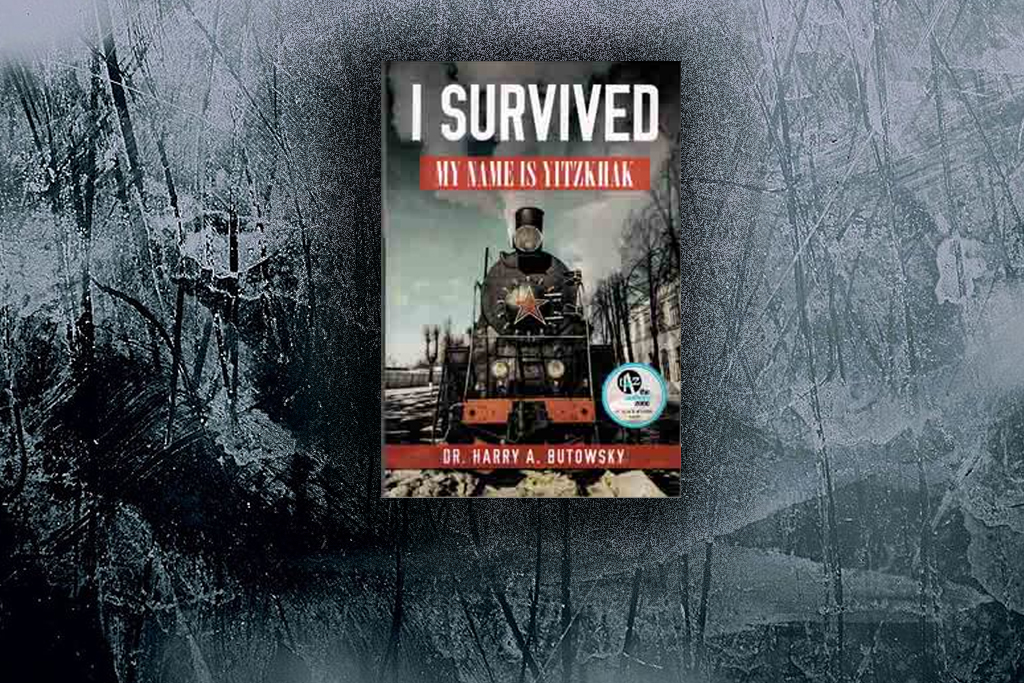

This book is based upon oral interviews the late Neiman gave to Harry A. Butowsky, a college historian who also worked in the Washington D.C. area with the National Parks Service.

Neiman makes no apology for stealing, whether it was from the Soviet and Polish Armies or from civilians whom he judged to be “speculators,” a term which also could describe his own black market dealings. In his view, he simply did what was necessary to survive in a world gone crazy.

When there were jobs available, Neiman was a jack of many trades. He was a butcher, a wood cutter, a soldier, a warehouseman, and a farmer, among other occupations. He gravitated to those jobs that offered the best possibilities for thieving food and other items that might be sold on the black market.

Neiman never got rich from his thefts and black market activities, but he at least was able to stave off the hunger that was the constant companion of Russian and Polish villagers and laborers, especially during the long winters of World War II. After the war, while living in DP camps, he continued to break rules in what he considered to be his survival mode. The book ends before Neiman immigrated to the United States, so we don’t know how or if he reformed in the land of the free.

Butowsky, narrating the story in Neiman’s voice, relates his wartime and postwar experiences clearly and in matter-of-fact fashion, allowing the facts, rather than emotion, to carry the story of Nazis’ barbarity and Soviet callousness and indifference. And yet, amid the dog-eat-dog world that Neiman found himself in as an orphaned teenager and young man, he both benefitted from and performed various acts of kindness.

Republished from San Diego Jewish World