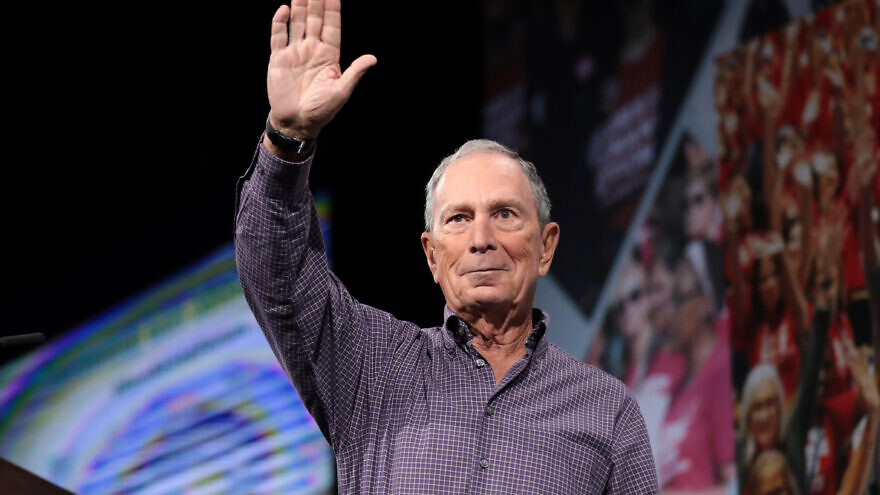

This week America got another Jewish candidate, in addition to another billionaire, into the 2020 presidential race. The entry of former New York City Mayor and Bloomberg L.P. CEO Michael Bloomberg into the battle for the Democratic Party presidential nomination has set off a wave of commentary about whether, as his supporters claim, he is the most electable Democrat. But as far as his opponents are concerned, the only relevant question to ask about Bloomberg’s effort is if the presidency can be bought in 2020.

Bloomberg joins Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders as the second Jew in the race, with financier Tom Steyer as the second billionaire. Some may count Steyer as a third Jew in the contest because his father was Jewish, though unlike the other two, he was not raised as a Jew and is, in fact, an active member of a Christian church.

What is perhaps most fascinating about Bloomberg’s candidacy is not his belief that a Democratic Party trending left will embrace a relatively centrist person possessing enormous wealth. Nor is it whether his unconventional strategy for winning the nomination—he intends to skip all the early primaries, refuse all campaign donations and spend a record amount of money on television ads, rather than expend effort on building a grassroots organization—is genius or hubris. Rather, when all is said and done, the most interesting thing about Bloomberg’s candidacy is that he may prove a point about when it is permissible to attack a Jewish billionaire for spending his money on politics.

As for Bloomberg becoming the next president, count me among those who are profoundly skeptical about his chances. I think the scenario that holds that he can parachute into the race, push aside former vice president Joe Biden and become the leading moderate—and then sweep to victory, despite the strength of liberal adversaries—is highly unlikely, if not completely delusionary.

With a net worth estimated by Forbes at $55.5 billion, Bloomberg is ranked as the ninth richest person in the world. By comparison, Steyer has only a paltry fortune of $1.6 billion to his name.

Bloomberg has already shown in his three successful runs for mayor in New York City that he is ready to spend as much as it takes to win. In 2009, he spent an astounding $102 million that garnered him 585,466 votes, eking out a 51 percent to 46 percent margin victory to secure his third term. At the same rate of $174 per vote, he could well manage to pay an equal or even far higher amount to replicate that result on a national scale, even though a conservative estimate of the cost would tally somewhere north of $12 billion. That’s a figure that would still leave Bloomberg and his children more than enough to get by on.

However, the really interesting point about Bloomberg and his money is not the unlikely prospect of his beating the other Democrats into submissions with endless mind-numbing television ads and then besting President Donald Trump with the same tactics. Rather, it’s the way his opponents are reacting to his plan to buy the White House, and the absence of any concerns that their criticisms are inherently anti-Semitic.

Many on the left and in the media have regularly flayed Republicans for criticizing the three leading donors to liberal and Democratic causes—hedge-fund billionaire George Soros, Bloomberg and Steyer—for the way they’ve tried to buy elections. Their assumption was that criticism of the trio was an act of anti-Semitism, despite a lack of proof that those who attacked them had any such motive. That assumption—that attacking these particular three Jewish billionaires was a dog whistle to anti-Semites—was always bogus.

It’s true that talk about Jews and money are a staple of classic anti-Semitic invective, as Rep. Ilhan Omar (D-Minn.) proved when, among other attacks on Jews and Israel, she said that congressional support for the Jewish state was “all about the Benjamins”—a belief that is echoed by her counterparts on the far-right.

When Jews are criticized for using money as Jews or to somehow further Jewish interests, both real and mythical, it is anti-Semitic.

Yet not every comment about a Jew spending money on politics is a product of prejudice. Sometimes, it’s just a genuine belief that someone is trying to use their financial wealth to unduly influence voters. It was no more out of bonds for conservatives to highlight the fact that Soros, Bloomberg and Steyer were injecting large amounts of money into particular districts or states to secure victories for causes or candidates they liked than it has been for Democrats to similarly attack conservative donors like the Koch brothers or Sheldon Adelson (who is also Jewish) for doing the same thing.

That’s why it is perfectly legitimate for Warren and Sanders to lambast Bloomberg for substituting his billions for their years of tireless fundraising and campaigning without giving anyone cause to say that they are invoking stereotypes about Jews and money. Bloomberg’s Jewish origins or his support for Israel have nothing to do with it. The same was true for GOP critics of Democratic mega-donors who happen to be Jewish or have Jewish connections.

No matter what you think about the barrage of criticisms of Bloomberg’s spending by his liberal foes, it won’t be evidence of their hostility to Jews. That’s something those who previously labeled similar critiques by Republicans as evidence of prejudice ought to take to heart. This point should also be remembered if Bloomberg becomes the Democratic nominee and GOP critics are warned not to mention his money, lest they be accused of fomenting hatred. The lesson here is that as long as the ones doing the bashing are liberals, then it just won’t be called anti-Semitism.