“Nec audiendi qui solent dicere, Vox populi, vox Dei, quum tumultuositas vulgi semper insaniae proxima sit (‘And those people should not be listened to who keep saying the voice of the people is the voice of God, since the riotousness of the crowd is always very close to madness’).” — Alcuin of York, an English scholar, clergyman, and poet (c. 735–804 C.E.)

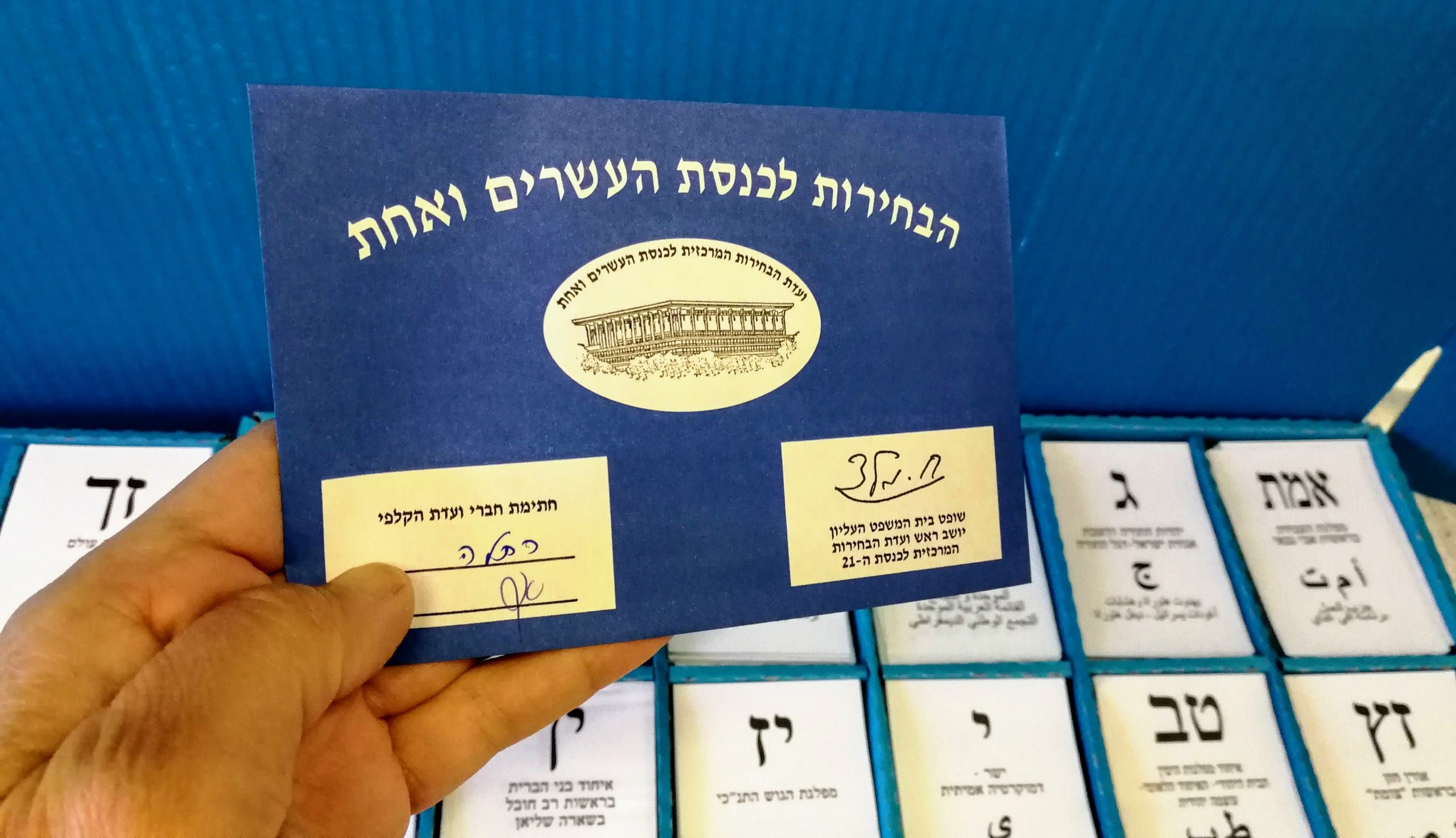

Israel is now hurtling towards its third national election within a year.

This was not an outcome precipitated by some unforeseen or uncontrollable force majeure. On the contrary, it was entirely the result—albeit, an entirely perverse and paradoxical one—of the free exercise of collective human volition.

It was perverse and paradoxical because it reflected the diametric opposite of the express desires of the individuals comprising the collectives involved in precipitating it.

Toxic quagmire of irreconcilable demands

As the inevitability of a new election drew inexorably closer—and the quagmire of the irreconcilable political demands of the potential coalition partners grew more viscous and more noxious—so the blame-game, the endeavor to attribute guilt for the undesirable outcome, spiraled to evermore shrill and venomous levels. Every political faction pointed accusatory fingers at every other faction.

Each party extolled its own “flexibility” and underscored its own selfless willingness for sacrifice to hobble together a coalition—any coalition-to avoid a dreaded third national ballot.

Thus, Likud castigated Blue and White for intractable anti-Netanyahu rejection, and excoriated Avigdor Lieberman for perfidy and betrayal of his right-wing constituency. Blue and White condemned the Likud for obsequious subservience to Netanyahu and putting the wishes of their indicted party leader above the needs of the nation. Lieberman slammed both for being inflexible and for secretly preferring new elections, in which they hope they would improve their positions, over forming a unity government with each other. In Blue and White itself, left-of-center members accused right-of-center members of preventing the creation of a coalition headed by their party, that relied on the support of the Arab Joint List.

So, to sum up how the third round of elections came about: No one wanted them, almost everyone voted for them, and everyone blamed everyone else, except themselves, for causing them.

Another perverse paradox

This brings us to the second perverse paradox.

Apart from Lieberman reneging on his pre-election pledges in April to help set up a right-wing coalition (or, at least, what many saw as such), the subsequent rounds of elections were in fact precipitated by the various parties ostensibly insisting on honoring their electoral pledges to their voters.

The right-wing parties maintained their ideological solidarity and allegiance to Netanyahu as their choice for premier. Blue and White refused to give up their undertaking not to join a government under an indicted prime minister; Lieberman kept to his (relatively new) commitment to eschew participation in what he dubbed a “Messianic ultra-Orthodox” coalition, despite the fact that he had done precisely that on numerous times in the past.

Thus, the event, which no one wanted (i.e., additional elections) came about precisely because the elected politicians strove to stick to their campaign promises and provide voters what they elected them for.

Dysfunctional or irrational?

Accordingly, the repeated failure to form a government is not really a failure of Israel’s democratic system as some have claimed, but rather a reflection of its success and its ability to accurately convey the will of the electorate, including its view of Netanyahu’s legal situation and the moral implications thereof!

Indeed, if this is the case—and there seems little grounds to think otherwise—the ongoing political saga in Israel leads unavoidably to one of two gloomy conclusions regarding the Israeli electorate as a functioning collective:

(a) It is either dysfunctional in that it cannot agree to provide any elected political entity, or any combination thereof, the power to govern—i.e., it cannot generate the collective will to allow the formation of a viable elected government; or

(b) It is irrational in that it has a collective desire to install a viable government, but insists on rewarding precisely those who thwart that desire.

Arguably, either possibility was clearly discernible in the last round of elections. After all, in the original elections in April, the formation of a viable right-wing coalition was eminently feasible until Avigdor Lieberman’s Yisrael Beiteinu faction, which had pledged to facilitate precisely such a coalition under Netanyahu, refused to do so. Indeed, had Lieberman honored his commitment, there would have been little difficulty in forming a governing coalition.

When the next elections came about in September, instead of punishing the very faction that frustrated the formation of a governing coalition, the electorate chose (paradoxically) to reward it, almost doubling Yisrael Beteinu’s strength in the Knesset and commensurately increasing its ability to torpedo the formation of any future coalition, which, of course, it did.

Worse, if current polls are anything to go by, Lieberman’s faction will retain more or less the same number of seats as it has today, leaving its obstructive power undiminished.

Accordingly, it would appear, that as a collective, the Israeli electorate is still resolved to sustain the ongoing political limbo—whether it is unwilling to confer the power on any elected political grouping the ability to form a viable government or despite the fact that it is willing to do so. In other words, it appears to be persisting with collective behavior that is either dysfunctional or irrational.

Can’t blame a dictator …

Of course, Israel’s elected politicians have been sorely reproached for the prevailing fiasco. Much has been made of the cost of the repeated elections and of how many classrooms could be built, hospital beds increased and roads upgraded with the sums required to conduct them.

This, of course, is as true as it is irrelevant. For the necessity of holding and re-holding elections is due to one thing and one thing alone: the election results, which reflect the will of the voters.

Had Israeli citizens voted differently, had they not empowered the very faction responsible for preventing the formation of a duly elected government (and which they knew to be responsible therefor), had Yisrael Beiteinu been punished, rather than rewarded, in September for blatantly violating its April pledges and received fewer votes than the required threshold to be admitted to the Knesset, then the country would in all likelihood have had a functioning government today.

There is an important lesson to be learned from all this on free choice and civic responsibility. Despite its many undoubted merits, democracy has one glaring detriment: There is never a dictator to blame for the fate that befalls the people. They, and they alone, hold the key to their destiny and for whatever befalls them.

Martin Sherman is the founder and executive director of the Israel Institute for Strategic Studies.