The Mingei International Museum’s current exhibition of Israeli crafts and design is a retrospective that incorporates aspects of the Jewish State’s history with what the exhibit’s curator, Smadar Samson, describes as four major themes of that nation’s experience.

These themes are 1) invoking the collective memory of the Jewish people; 2) creating something from nothing; 3) restlessness and innovation; and 4) transitioning into global culture.

Samson is also the curator of the Cottage of Israel, which is one of the cottages in Balboa Park’s mullti-structure House of Pacific Relations. She said that the Cottage of Israel has the distinction of being one of the first venues in the United States to fly the Israeli flag after that country’s creation in 1948. So, in a sense, the exhibition running through September 3rd at the Mingei not only celebrates Israel’s 70th birthday, but the cottage’s birthday as well.

The exhibition almost didn’t happen. The Mingei Museum had been scheduled to undergo extensive renovations during this period, according to its executive director Rob Sidner. However, when Samson approached the museum about holding the exhibition in honor of Israel’s 70th birthday, he said he decided that it would doubly benefit the museum. First, it would bring an interesting retrospective exhibition to the public, and, second, it would allow the Mingei more time for fundraising before closing for the renovation.

Asked how the Israeli exhibition compares with others mounted by the Mingei in the past, Sidner responded: “I would say that it really is its own thing – sui generis – precisely because of Israel’s history. Israel is very new as a modern state, with people coming together from all over the world—especially from Europe and the Middle East, and this country—so it’s a melting pot in a way, but it hasn’t really melted. Jewish people are famous for having many points of view and not easily giving them up, and that has allowed a wonderful richness and diversity to exist side by side.”

Seventy years of craft and design history is not very long as compared to the experiences of the centuries-old nations of Europe and Asia, where generations of the same families were crafts people. So, in choosing some 125 artifacts for the exhibit, Samson decided to ask Israeli designers, collectors, and museums to lend some works that would help visitors glimpse both the modern nation of Israel’s pre-history and the evolution of its crafts and design. For example, early in the exhibit, there is a wall-hanging that 19th Century tourists like Mark Twain might have seen, which depicted the Kotel (Western Wall) and the houses around it. “It really shows how isolated this society was; it was completely oblivious to the arts and crafts movement at the time, and also they (artists) were restricted by the Second Commandment,” Samson said. Her reference was to the prohibition against making graven images, which generally was considered to be a prohibition against depicting humans, as they were believed to have been created in God’s image.

Zionists of the late 19th and 20th centuries had an impact on Israeli arts and crafts, none more so than Boris Schatz, the founder in 1906 of the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design in Jerusalem. The name “Bezalel” is after the artisan mentioned in the Bible who designed the Tabernacle and the Ark of the Covenant. For Schatz, formerly a sculptor in the court of Bulgaria’s King Ferdinand, the Bezalel Academy represented an opportunity for the pious Jews of Jerusalem and Tsfat, who had been existing primarily on alms, to develop a commercial enterprise. Atop the Academy, Schatz “erected a huge menorah,” indicative of his desire to “merge the symbolism of the East with the styles of the West,” according to Samson.

Schatz brought with him from Europe artists who were trained in the art nouveau style. “You could see that influence in their work, but the subject matter came from the local history and environment, from the local flora and fauna of Israel,” the curator said. Typical subjects were “the biblical figures of the spies who came to Israel, or Miriam dancing. Bezalel concentrated on having the content reflect our heritage.”

Israel is a small country, approximately the same size as the U.S. state of New Jersey. It is poor in natural resources, but rich in imagination. The ethos in Israel is to make do with what you have. During World War I, when the British fought the Turks for control of Palestine (as Israel was then named), artillery shells littered the landscape. Pointing to one art work on exhibit, Samson said: “Students and the teachers went outside the Bezalel school and picked up this artillery shell and applied a beautiful Damascene technique—a technique of layering in different materials—and carved it with images of holy places. It was a very resourceful solution.”

Theodor Herzl and a new dawn

Many German Jewish artists who immigrated to Israel were followers of the Bauhaus movement, “which can be described as the three F’s—Form Follows Function,” Samson said. Bauhaus architects designed simple homes without ornamentation. Bauhaus ceramicists preferred simple designs, with no ornamentation except perhaps for Hebrew lettering. “The head of the department of the Bezalel School worked on designing a completely new typography of the Hebrew language,” Samson noted.

As we were about to pass from the first room of the exhibit into the second, Samson lingered in front of a tapestry showing the founder of Zionism, Theodor Herzl, in his iconic pose, leaning over the balcony in Basel, Switzerland, where a Zionist Congress had been held. The scene he looks over is a rising sun, a new dawn, symbolizing the anticipated fortunes of the Jews once they had their own state.

The wall in the museum was specially constructed “so people can move into the light of Israel,” Samson said.

In the next room, she noted that when David Ben-Gurion, Israel’s first prime minister, declared his nation’s independence on May 14,1948, he did so at the art museum in Tel Aviv. It was the only accessible building at the time, said Samson, “but I think it was not a coincidence.” She said even though the new nation suffered warfare, privation, and the stress of a doubling population through the immigration of Jews from Europe and the Middle East, “people wanted to express themselves.”

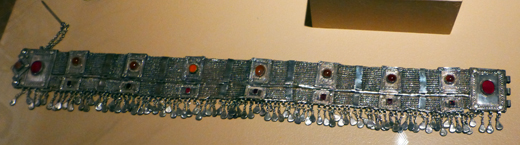

Bridal belt in Yemenite silverwork

She told of the Ben David family from Yemen, who crafted in silver a beautiful belt to be worn by a bride – not only to enhance a future wedding, but to show administrators of a temporary resettlement camp in Israel that there indeed was such a craft in Yemen as silversmithing, and that Yemenite Jews were capable to do many things, not just digging with shovels.

Dress by Roly Ben Josef

Roly Ben Josef, a young immigrant from Bulgaria, while working at her father’s textile factory, which specialized in towels, utilized that material to make a colorful dress, winning her the distinction of being Israel’s first fashion designer. Within a few years, her creations were featured in such U.S. department stores as Macy’s.

A section of the exhibition focuses on “the three mothers’ of Israeli ceramics – Chava Samuel, Hanna Zuntz, and Hedwig Grossman. Each had her own style, according to Samson.

Chava Samuel was the first to introduce glazing to Israel. “She incorporated local figures of Eretz Israel—delicate figures, a woman in the market, a person on a horse. But her importance was that in 1934 she established the first ceramic studio in Israel, in which she expressed herself as an independent artist,” Samson said. Hanna Zuntz, a follower of the Bauhaus movement, “used to go to the Dead Sea and the Negev to pick up the clay with her own hands because she believed we should use whatever we have. When she was 90, she was still doing ceramics, and her daughter said she never saw her mother take clay from a plastic bag.” Hedwig Grossman “didn’t believe in glazing; she believed the Israeli people should be faithful to the color of the land. She did very simple turning wheel ceramics only mixed with representative colors of the arid land.”

Although each of these women hoped to establish a definitive style of Israeli ceramics, none succeeded. “There is nothing distinctly Israeli about ceramics; there is nothing that you can call Israeli in any medium,” said Samson. “Therefore, this exposition tries to expose an Israeli mindset, a way of thinking that is nourished by metaphors, values, and the conditions of life in Israel. When they move from one object to another, visitors will be able to discern some of the cultural codes in these objects.”

One code is the collective memory of the Israel and Judea of biblical days. Menorahs and hannukiahs are examples found in the exhibition.

Expulsion from Paradise

Another code is the idea of working with limited resources, even re-purposing otherwise used-up resources. On exhibit light made from the metal underpinnings of an umbrella.

A third code is “restlessness and innovation,” Samson said. She pointed to a ceramic pot called “Expulsion from Paradise,” by Alon Gil. It shows Adam and Eve, with fig leaves. Their faces are those of popular musicians. Eve is Um Koltom, an Egyptian diva, and Adam is Zohar Argov, a popular Israeli singer. The artist “wanted to reflect the tension between men and women, politics, and the conflict,” Samson said. “This is an example of how the notion of restlessness is translated into art.”

Jews, “the people of the book,” have a natural reluctance to throw books away. When the Internet caused encyclopedias to become unnecessary as storehouses of information, Israelis typically would stack their multi-volume sets outside their houses, hoping someone would pick them up and put them to use. Artist Cecilia Vitas Volcoff Kashe did just that; she used lasers to cut into the encyclopedias to create three dimensional artifacts.

A fourth code, said Samson, was recognition of the necessity to transition from nationally-conscious art to that bespeaking the global culture. This often is done with a sense of humor: for example, soup ladles turned into “Nessies,” the nickname for Scotland’s mythic Loch Ness Monster.

Ethiopian representation, from left, of Leah, Rachel, Jacob, Abraham, Sara, Isaac, Rebecca

The exhibition includes not only the work of European and Middle Eastern Jews, but also those of various minorities, including Ethiopian Jews, Palestinians, and Druze. One Ethiopian work depicts the Four Matriarchs and the Three Patriarchs of the Bible. A Palestinian work from Gaza is a traditional ceramic, blackened by the smoke of burning barley husks. A Druze work is a copper tray, designed with the logos of Facebook and What’s App—a commentary on how “the hill of yelling” where Druze of Israel and Druze of Syria would yell family news to each other, has been replaced by modern technology.

Republished from San Diego Jewish World