A Boy in Winter appears initially to be an firsthand account, told from the viewpoints of the various individuals involved – both directly and indirectly – in the roundup and murder of the Jews of a small Ukrainian town during the Holocaust. The events are portrayed by means of a graphic and sometimes shocking narrative.

We first encounter two young boys, brothers, one considerably smaller than the other, hurrying past the houses of the town in the early morning. This and other sections of the book are written in the present tense, giving the reader a sense of immediacy, as if he/she is watching events unfolding in front of him/her. I personally do not like that writing convention. Although it seems to be increasingly common as an authorial stance, I still prefer the traditional literary approach, using the past tense.

After witnessing the boys’ escape from the town the reader is introduced to Pohl, the German engineer who has been sent to the region to supervise the construction of a highway through the dank, damp terrain. We first encounter Pohl’s human side as he sits in his boarding-house room and engages in a mental conversation with his wife, Dorle, as he experiences the first stirrings of anger at the way the local population is being treated by the invading German army.

The next brief scene shows us the elderly local schoolmaster caught up in the developing tragedy as soldiers shout in German, ordering all Jews to leave their homes and assemble outside. The schoolmaster and his even older mother are confused and bewildered by the insults and instructions yelled at them. They are joined by other Jews as they are all herded (the word Pohl uses to describe the scene) towards the local brickworks. They have all been told to bring warm clothing and provisions for a journey of three days, and are made to stand in an enclosed space for many hours.

Pohl gets into his car and drives through the countryside to the construction site, inspects the building work, and laments the lack of adequate labourers. Meanwhile, in a farmstead just outside the town Yasia, a young girl, the eldest of many children, helps with the housework and childcare, shares the work on the farm and, leading a horse, also goes to the market with apples to be sold. Although she is barely out of puberty, we learn about her love for local lad, Kolya, who has been conscripted by the Russians. We later learn that he has deserted from the Soviet army and returned to the town, where he joins the local militia.

At this point Nazi troops, accompanied by the Ukrainian militia, including Kolya, enter the town en masse, and the two armed groups combine, first in gathering all the Jews in one spot, then in slaughtering them. The local population is aware of what is happening, but is unable (or unwilling) to intervene. Yasya is unable to return home and happens to come across the two boys. Seemingly unknowingly, she at first hides them in an attic, but after a couple of days is told to leave with them.

The main part of the book describes the harrowing journey of the three through the cold, wet countryside, struggling to get through the marshy ground. All three are hungry, cold, and exhausted after several days of walking, with both the older brother, Yankel, and Tasia sharing the burden of carrying the younger boy.

Eventually the children reach an isolated village, where they are given shelter. The end of the book reveals how the two Jewish boys were eventually accepted by the villagers, though what happens to them in later life is not clear.

The book brings the privation, fear, and horror of the time of the Holocaust graphically to life.

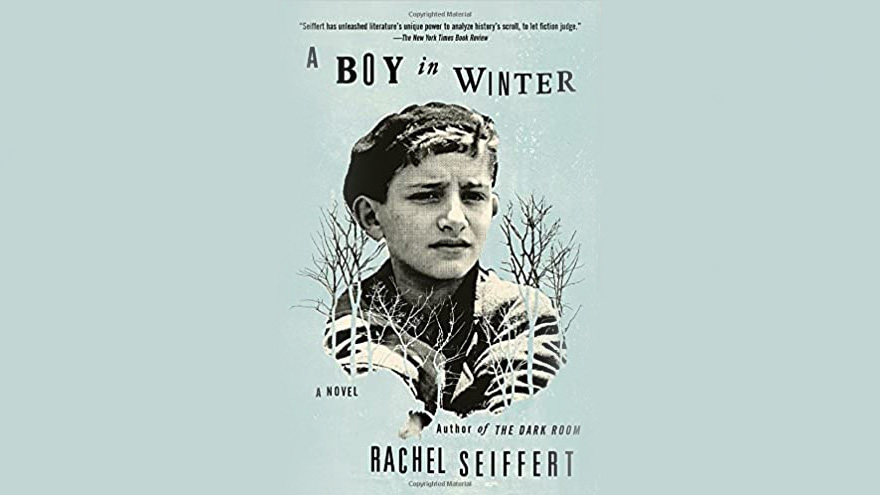

A Boy in Winter by Rachel Seiffert; Virago UK, 2020; ISBN: 9781844-089963; 256 pages; £8.99 ($12.37).

Republished from San Diego Jewish World