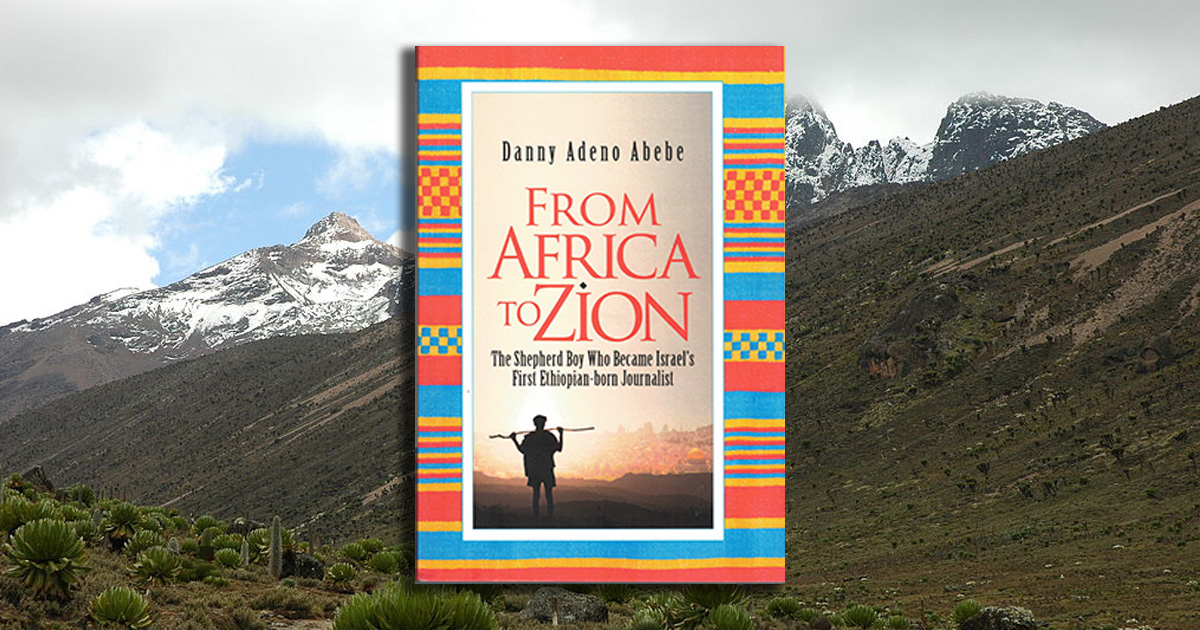

From Africa to Zion: The Shepherd Boy Who Became Israel’s First Ethiopian-born Journalist; a memoir by Danny Adeno Abebe; Yedioth Ahronoth, Chemed Books; © 2021, translated from Hebrew; ISBN 9789652-012869; 404 pages.

This is a remarkable memoir that takes us from the author’s childhood in a rural Ethiopian village without electricity or running water through his perilous journey to a crowded, multi-ethnic refugee camp in the Sudan, where disease and crime were rampant, and onto his arrival to the modern world of Israel, in which his family were initially mystified by such conveniences as toilets and refrigerators.

Amid such wonders, the youthful Abede wanted nothing more to become fully Israeli, but along the way he learned the color of his skin was an impediment to total integration. Although White Israelis cooed how cute and nice Ethiopian Jews were, they were actually quite racist in their behavior, no more so than when Magen David Adom – the Israeli equivalent of the Red Cross – on a wholesale basis dumped blood donated by Ethiopians for fear their blood might be laden with AIDS or other contaminants.

Slowly, Abede came to realize that White Israeli Jews underestimated and undervalued Black Jews – a pattern similar to the way that Jews from Europe (Ashkenazim) had looked down upon Jews from North Africa and the Middle East (Sephardim and Mizrachim). However, while this was a source of bitter disappointment; it did not result in his total alienation from Israeli society. In fact, after winning acceptance as an IDF Radio Journalist, he went on to a distinguished career with the daily Yedioth Ahronoth, which at the time was Israel’s largest newspaper. In his memoir, Abede recognizes and salutes some of the White journalists who were his mentors.

While Abede covered numerous stories unrelated to Ethiopian Jews, his specialty was stories about the trials and tribulations of the Ethiopian Jewish community. He was sympathetic, of course, to his uprooted people’s plight, but he also was unafraid to expose such scandals within that community as unscrupulous shamans who preyed on some Ethiopian Jews’ fears and superstitions; racism within the Ethiopian Jewish community, particularly toward former Black slaves or their descendants; and the abuses, favoritism, corruption and rapes attributable to members of the Ethiopian Jewish committee members who had been picked by Mossad to coordinate aid to Ethiopian Jewish refugees in the Sudan.

He also wrote about returning to the villages of their births with his wife Aviva, an Ethiopian Jew who he met in Israel, and their children. Showing his children from whence he had come helped him clarify his feelings about the land of his birth and the land of his children’s birth, and prompted his children, who previously knew little of their heritage, to begin to incorporate some Ethiopian foods and customs into their daily lives.

Abede also served for two years as a shaliach, or emissary, for the World Zionist Organization and Habonim-Dror in post-apartheid South Africa, where he witnessed members of the Jewish community enjoying lives of luxury compared to most of the nation’s Black population. He set into motion programs by which the local Jewish community and the government of Israel reached out to Black South Africans with such projects as blankets for homeless people, tutoring students in Soweto, and rebuilding and restocking the deteriorating public library in Kliptown.

Overall, the book makes for wonderful, eye-opening reading. I hope it will prompt readers to introspection about their own attitudes. It’s fair to call Abede’s life a true Jewish odyssey.

Republished from San Diego Jewish World