Adam Levitz, a 44-year-old married father of three, was in liver failure. Things were getting worse, and he knew it. On Dec. 20, he received a new liver and a new lease on life. His donor, Rabbi Ephraim Simon, is one of only a handful of individuals to have ever donated both a kidney and a liver—a procedure most hospitals won’t even allow.

The two men had never met until just days before the life-saving surgery, but Simon says that’s exactly what he was looking for.

“As a rabbi, I do a lot of talking about love, doing things for others and altruism,” says the 50-year-old father of nine who co-directs Chabad of Bergen County in Teaneck, N.J., with his wife, Nechamy. “A rabbi’s greatest sermon and a parent’s greatest lecture is the way they live their lives,” says the rabbi, who is still in Cleveland for observation following the surgery. “The Rebbe imbued his Chassidim with Ahavas Yisrael[‘love for a fellow Jew’]. It’s something we all speak about, but how often do we have the opportunity to really set ourselves aside for another? This was my opportunity to do that, and I didn’t want to let it go. Adam allowed me to actually give the gift of life, perhaps the greatest chesed, kindness, I can imagine.”

The rabbi’s route to donation was not an easy one.

It was a circuitous chain of kindness that involved many, most notably Chaya Lipschutz, a woman from Brooklyn, N.Y., who donated a kidney to a stranger and devoted her life to matching kidney donors and recipients.

Since she had matched him up with the recipient of the kidney that he donated in 2009, he approached her again and asked if she was aware of anyone who could make use of his liver.

“Rabbi Simon approached me in 2012 and told me that he wanted to donate a portion of his liver altruistically,” says Lipschutz. “That is unique. It is extremely rare for someone to donate a kidney and then a liver, but he was so very motivated to give this gift to someone.”

While Lipschutz is aware of two individuals who donated kidneys and then went on to donate their livers to children (who require just a small portion of an adult liver), at the time Simon was the only kidney donor she encountered who wanted to give his liver to an adult.

Through the introduction of Chanie Wilhelm of Chabad of Milford, Conn., Lipschutz had been aware of Levitz, a resident of Long Island whose parents were leading members of Wilhelm’s congregation.

Diagnosed with Crohn’s disease at age 15, Levitz was no stranger to pain and medical complications and managed to live a productive life despite the condition, which has no known cure. However, when the disease affected his liver, things got much worse. Levitz had been working in finance until his health prevented him from continuing. “Around nine years ago, the Crohn’s caused PSC, short for ‘primary sclerosing cholangitis,’ and I was hospitalized numerous times in the past three years.”

Levitz was placed on a donor registry in several places and had even rushed twice to Philadelphia in the hopes of receiving livers from deceased donors, but both times, his hopes were dashed. In one case, the liver wasn’t in good enough condition, and the other was too large.

In retrospect, Levitz reflects, it was all God’s hand since his doctors had advised him that he really needed a liver from a living donor.

In the meantime, Simon had his share of false starts as well, prospective liver recipients who turned out not to be suitable for him. “For years, Rabbi Simon kept on hoping that there was someone out there who could use his liver, and he was so grateful every time we thought we found someone,” says Lipschutz, who has been making donor-recipient matches since 2005. “He just so wanted to help others.”

Through Lipschutz’s networking, the shidduch was made, but things were far from simple.

As a previous donor, Simon was considered by most hospitals to be high-risk, and so they refused to consider him as a candidate. In addition, donors who do not know their recipients are viewed with suspicion and often categorically rejected on those grounds alone.

Cleveland Clinic’s unique philosophy

The only place in the country they were able to find that would do the surgery for them was Ohio’s acclaimed Cleveland Clinic, which has a unique philosophy about working with people to save lives at all costs.

The date for the surgery was set for Dec. 20, but the rabbi had a lot to do before he would be able to check himself into the hospital for several weeks.

“Giving a liver makes donating a kidney look like a walk in the park. With liver donation, the surgery is very invasive and the recovery can take several weeks. It’s a very big deal.” Since he would be out of commission for the last few weeks of 2018, when he traditionally raises the funds needed to cover the year’s operating expenses for his Chabad House, he hustled to get things set up several weeks earlier.

“I could never have done this without key partners,” says the rabbi with characteristic humility. “First and foremost is my wife Nechamy, who has been with me throughout both of my donations. It is easier to be in pain than to have to sit there and watch someone you love suffer, so she is the one who deserves to be recognized. Then there are my children who have stepped up to take care of things in our absence. My 22-year-old son and 19-year-old daughter have taken over the household, and knowing that things are running smoothly at home has allowed us to focus on the surgery and recovery. And then there is the community—both our Chabad congregation and the broader Teaneck community—which has rallied around us and supported us with prayers, well wishes and more. And much of my day-to-day work has been taken over by my fellow shliach, youth and teen director Rabbi Michoel Goldin.”

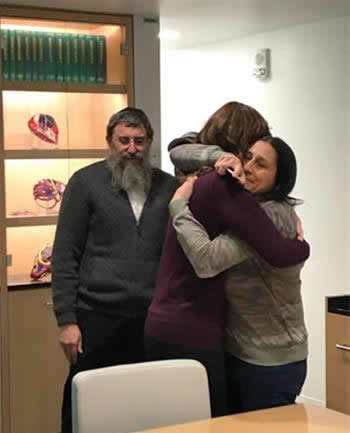

Before entering into surgery (the two men were operated in adjoining rooms), Simon and Levitz met for the first time, in an experience both described as “emotional.”

‘He was a new person’

However, Simon says the more moving meeting took place two days after the procedure when he was able to see the effect of his gift. “His skin color, the light in his eyes, his movement, everything was new and different,” says the rabbi. “You could tell that he was a new person. He was living again, and G‑d had allowed me to be a part of it.”

During the procedure, when the doctors opened Levitz and removed his liver, they saw that it was even worse than they had previously estimated. Shrunken and hard, it was failing fast, and if they would have waited even another few days, it was not clear if the surgery would have still been viable.

“I am so thankful to God and to Rabbi Simon, whom I call my guardian angel. He represents everything that I have grown to love and respect about Chabad. He never once asked me how religious I am or anything else. I was a fellow human being, a fellow Jew, and he was happy to be able to help me.”

Having grown up affiliated with an Orthodox congregation but not strictly observant, Levitz says many of his family members have recently become involved with Chabad in their hometowns. His youngest son currently attends Hebrew School at Town of Oyster Bay Chabad near his home in Woodbury, N.Y.

Despite his exposure to Chabad rabbis and their open approach, Levitz says he is still trying to “wrap [his] head around the rabbi’s thought process. Every time we meet, he tells me how grateful he is for allowing him to save my life. With G‑d’s help, I’m going to be able to watch my kids grow up because of the mitzvah he did. He saved me, and here he is thanking me.”