I recently stumbled upon a photography book shot by the acclaimed Life magazine wartime photographer John Phillips. The large, innocuous-looking book was simply titled, A Will to Survive. After flipping through the pages, I realized I entered a time capsule that memorializes the Arab destruction of Jerusalem’s ancient Jewish Quarter in 1948.

Not only is it a dramatic firsthand account of the fall of the Jewish Quarter in 1948, but it documents the Arab Legion’s scorched-earth tactics that razed and burned to the ground every structure there, including all its synagogues and yeshivahs. The Arabs expelled all of the city’s residents, mainly defenseless, old Orthodox Jews. They were given about an hour to vacate homes that most extended families had lived in for centuries.

To get his shots in May 1948, Phillips posed undercover in Jerusalem as a British officer in the Arab Legion. He also smuggled out his photos to avoid Arab censors who were eager to keep the sacking of the Jewish Quarter secret.

In 2017, the Palestinians loudly claimed “ownership” of the eastern half of Jerusalem when President Donald Trump proposed to move the U.S. embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem. The Palestinians asserted it’s their “capital.”

Lost in the frenzy was the fact that the ancient and sacred Jewish Quarter itself is in the eastern half of Jerusalem. It’s where the Western Wall, also known as the “Wailing Wall” or the Kotel, sits.

From May 10-18 of this year, Hamas unleashed more than 4,000 unguided rockets towards Israeli population centers to reinforce the Palestinian claims on the city. They did it as an Israeli High Court decision was pending on the eviction of Palestinian squatters in Sheik Jarrah who had seized Jewish homes in the eastern half of the city after the Jews were expelled by the Arab Legion.

Alarmingly, it appears that the Biden administration is sympathetic to Palestinian claims. It apparently plans to reopen a “consulate” in eastern Jerusalem to serve as a de facto “embassy” for the Palestinians.

The battle for the Old Quarter occurred in another month of May—from May 18-28, 1948. Philips recalled his time in the Old City then: “In the next eleven days, recording the destruction of the Jewish Quarter was to be my life.”

He served as one of Life magazine’s top photographers for 50 years. Britain’s National Portrait Gallery called him “the ‘Grandgodfather (sic) of photojournalism.’ ”

Phillips faced personal danger to do the shoot. He entered the Middle East undercover and wore the uniform of the Arab Legion, a British-created Arab army led by British officers, many of whom stayed on with their units to fight the Jews. “Mistaking me for a British officer, the Arab populace left me alone,” he wrote.

He was appalled about the Arab censorship. “Aware that the sack of the Jewish Quarter would shock the western world, Arab authorities across the Middle East tried to prevent the news from leaking out. Jerusalem could not be mentioned under any circumstances,” he wrote.

“I knew my pictures of the agony of the Jewish Quarter would end up in a censor’s wastepaper basket. I did not want this to happen and decided to smuggle them out of the Middle East.”

Phillips first job was to meet the pro-Nazi Arab fanatic, Fawzi al-Qawuqji, the field commander of the so-called Arab Liberation Army—a separate, brutal volunteer force specifically created to battle the Jews.

During the Second World War, Fawzi lived in Nazi Germany alongside Haj Amin al-Husseini, the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, and held the official rank of colonel in the Wehrmacht, the German army. The Nazis awarded Fawzi a chauffeured car and an apartment, along with other privileges.

Impulsively, Fawzi invited Phillips to lunch. He wrote that he was offended by what he saw. “There was a brutishness about the way they roared with laughter and slapped their thighs in delight at the prospect of wallowing in Jewish blood,” he wrote.

Afterwards, Philips ran into a Yugoslav mercenary who had witnessed their lunch meeting. “What rabble,” Phillips wrote, quoting the mercenary. “They have no idea what a real fighting outfit is like. I do. I was with the Waffen S.S.”

In fact, that soldier was not alone. The ranks of Arab Liberation Army included demobilized Nazi Wehrmacht Army soldiers, including the brutal SS, along with pro-Nazi mercenary forces from across Europe.

Phillips admired the Jewish defiance. “While the Old Quarter might well be indefensible, they would defend it. This was the Jerusalem that Jewish people around the world asked to return to in their prayers.”

The pre-war atmospherics shocked Phillips, a veteran World War II photographer. “Weapons were peddled on Arab street corners as they were Jaffa oranges. British deserters, German S.S., Polish and Yugoslav mercenaries hired by the Arabs performed acts of sabotage.”

Phillips traveled the city with a British deserter. He was astonished by the destruction of its synagogues. “Whenever we paused to catch our breath, all I seemed to see were damaged synagogues,” he wrote.

He also saw the destruction of the famed Pirate Josef Synagogue. “From a spot near the Wailing Wall I could see Porat Josef synagogue rising in the distance across no-man’s-land. The synagogue, with its adjoining Talmudic schools and academy, was disintegrating behind billows of smoke. The massive walls were coming down in a rising torrent of stone debris. Stunned by this spectacle of wanton destruction, I wondered how many tons of TNT the Arab Liberation Army would squander to reduce this seat of learning to dust.”

For 11 days and nights, the battle raged. On May 28, Jerusalem fell to the Arabs. “By day the Arabs blasted their way into the Jewish Quarter with their artillery,” wrote Phillips. “On May 28 the exhausted Israeli fighters surrendered.”

Eventually, Jerusalem Mayor Mordechai Weingarten walked in to sign the surrender documents.

The surrender of the Jewish Quarter now was official. But the city’s tragedy was only beginning. “Had any Jews decided to remain in the Old City he would have been homeless within hours and probably dead by nightfall. Most of the civilians were Orthodox Jews. The men wore beards and side curls, wide-brimmed black felt hats and long black coats. The women wore babushkas. They were descendants of families that had lived in the Jewish Quarter for centuries. Now they were given just one hour to pack and get ready to leave.”

He describes the stunned civilians. “Dazed by the shelling, the civilians gathered up their belongings and trudged off to Ashkenazi Square.”

After the Jews fled, Phillips walked back to witness wild Arab looting and arson. “Arab civilians … had come leaping over the rooftops like a swarm of locusts to loot. In their frenzied path fires sprang up. Black smoke billowed out of windows, while bright yellow flames licked wooden balconies. The entire quarter was now afire. The smell of burning mingled with the stench of death.”

Phillips continued to follow the fires. “Outside the Jewish Quarter burned like a pyre. On May 29 the Jewish Quarter was charred and a burned-out shell. Down Beit El a proud Moslem led the way, followed by his barefoot wife carrying three wooden containers of Sephardic scrolls from a nearby synagogue.”

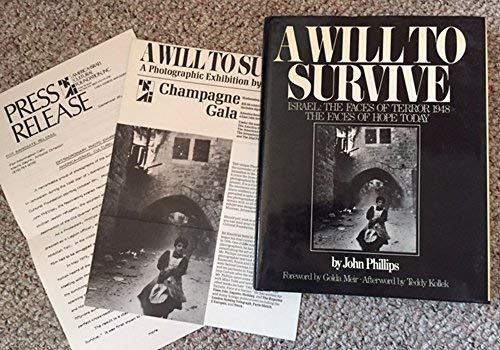

Thirty years later, in 1976, Phillips published Survive. Many of his photos were unveiled at Jerusalem’s Israel Museum. Former Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir wrote a short introduction to the book.

With the help of then-Jerusalem Mayor Teddy Kollek, he was able to meet with 51 of the survivors he had photographed.

What Phillips said affected him was the Jews’ complete lack of self-pity. “What struck me most while talking to these people, from the Chief Rabbi of Haifa to a Jerusalem housekeeper, was that none indulged in self-pity.”

Today’s Jews still don’t seek pity, but they should demand justice. The sacredness of the Old Jewish Quarter and its brutal destruction by the Arabs need to be widely republicized. There needs to be an international historical reckoning of their 1948 ethnic cleansing. Most importantly, the Jewish community must stand up for historical truths and strongly denounce the Palestinians’ baseless claims for the eastern part of the city.

Richard Pollock is a retired national journalist who lives in Washington, D.C.