The Science History Institute has acquired an amazing collection of correspondence, books, photographs and scientific notes belonging to Jewish German chemist Georg Bredig, announced the Philadelphia museum on Tuesday.

The collection spans decades, from the late 19th century, just as the field of physical chemistry was emerging, to the 1930s and the horrors faced by the Jewish community as the Nazis rose to power. The archive has never been made public. This acquisition was made possible by the generous support of the Walder Foundation.

There is extensive correspondence with the founding fathers of the field, including many early Nobel laureates in chemistry.

“As longtime funders of Holocaust education, Dr. Walder and I are proud to support the acquisition of the Bredig archive,” said Walder Foundation president and executive director Elizabeth Walder. “We know that this collection will provide history and science scholars alike a unique vantage point for uncovering some of the untold stories of this tumultuous period in world history.”

Bredig introduced the model reaction methodology to catalytic research, discovered and explored new catalytic phenomena, and discovered and investigated asymmetric catalysis.

Moreover, he explored the relationships between catalytic activity and the physical state of metals. The earliest documents in the archive date from the late 19th century and provide a snapshot of the field of physical chemistry in its early years.

There is extensive correspondence with the founding fathers of the field, including many early Nobel laureates in chemistry, such as Jacobus Henricus van’t Hoff, Svante Arrhenius, Fritz Haber and Wilhelm Ostwald.

The post-1933 collection items document a very different story. Bredig, along with his family and Jewish colleagues, struggled to survive under the increasingly oppressive Nazi regime. Some managed to flee to other countries, while others were not so lucky.

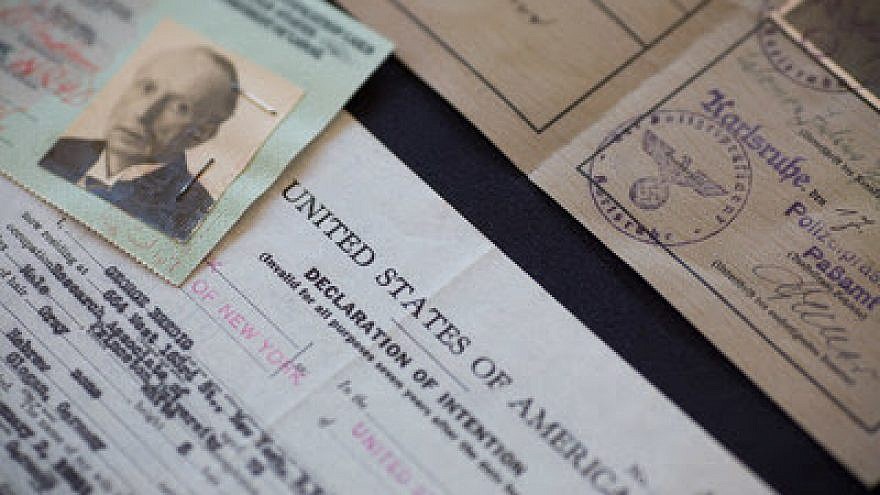

Their stories unfold through the letters describing their situations in detail, from requests for food and clothing for detainees to the desire to resume their work and their normal routines. Many of the letters and documents relate to Bredig’s attempts to leave Nazi-occupied Europe. Included in the collections are his German identification papers and passport, both marked with a “J.”

Bredig recognized the Nazis would likely destroy his personal library and archive, and his efforts to ensure its survival nearly cost him his life.

In a 1939 letter to his son, Max, Bredig wrote, “Yesterday I sent as a package to you the three green volumes I-III of my opera omnia. The rest IV-VII in green volumes will follow in the next week or so. … It is very dear to me that after my death the one and the other will end up in good hands (for an obituary and also for reference). In case you don’t want to keep it, give it to a university library, preferably one abroad, or to a good friend. Under no circumstances do I want it to be wasted/lost, given away or tossed! It should give witness over my life’s work.”

The collection was smuggled out of Nazi Germany to the van’t Hoff laboratory in the Netherlands, where it remained for the duration of the war.

In 1946, it was shipped to the Bredig family in the United States.

Funding from the Laurie Landeau Foundation will provide for conservation and preservation of the archive. The Institute plans to make the collection available to researchers and to develop related public programming in the coming months.