One of the world’s most confounding literary mysteries may finally be, in part, solved: the author of the mysterious and as-yet untranslatable Voynich manuscript has been identified as a Jewish physician based in northern Italy, an expert in medieval manuscripts has claimed.

The Voynich manuscript is an illustrated book printed on vellum written entirely in an indecipherable script, leaving scholars and code-breakers scratching their heads since it re-emerged a century ago.

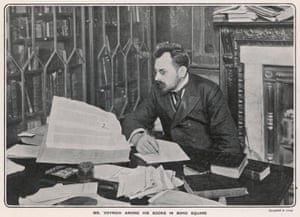

Writing in the foreword of a new facsimile of the 15th-century codex, Stephen Skinner claims visual clues in each section provide evidence of the manuscript’s author. If proved true, Skinner believes his theory will help unlock more secrets of the coded manuscript.

The doctor, whose work includes editing the spiritual diaries of the Tudor mystic John Dee, believes the illustrations show communal Jewish baths called mikvah, which are still used in Orthodox Judaism to clean women after childbirth or menstruation.

Pointing to the fact that the pictures show only nude women and no men, Skinner told the Guardian: “The only place you see women like that bathing together in Europe

Literary whodunnit … a page from the Voynich manuscript. Photograph: Alamy

Literary whodunnit … a page from the Voynich manuscript. Photograph: Alamy

at that time was in the purification baths that have been used by Orthodox Jews for the last 2,000 years.”

He believes the drawings were of an invention designed by the mysterious author that aimed to ensure an efficient supply of clean water to a mikvah. “I think there is no other explanation for what they are: it is either rank fantasy by the author – which doesn’t really fit with the medical, herbal and cosmological sections of the manuscript – or it is a mikvah,” he said.

Other evidence Skinner uses to support his theory include the lack of Christian symbolism in the manuscript – unusual at a time of deep religious superstition, as the Inquisition enforced orthodox religion and punished any hint of heresy. “There are no saints or crosses, not even in the cosmological sections,” he said.Considered in addition to the absence of religious symbolism, Skinner said, visual clues in the manuscript suggest its author was a Jewish physician and herbalist. Many of the plants depicted, alongside astrological charts, are medicinal herbs, such as opium and cannabis. “In those days, doctors had to be astrologers as well, so they could determine the nature of an illness and treatment.”

Although Jews were persecuted in the Inquisition, they were in demand as doctors due to their knowledge of Mediterranean botany, he added.

A visual clue to the geographical origin of the manuscript in northern Italy lies in a sketch of a castle with a “swallow-tail” on one page. The unusual design, Skinner believes, is a Ghibelline fortification found only in castles in northern Italy in the 15th century. Many of the region’s towns, such as Pisa, had significant Jewish populations and could have inspired the Germanic style of some of the illustrations because the ruling family was allied to the German Holy Roman Emperor, instead of the pope.

He admitted his theory will have to be rigorously tested by other scholars, but added that he felt “85% certain” he was right. Skinner, who is an expert in medieval esoteric manuscripts, said he was now searching European Jewish books from the period for similar language, codes, scripts or linguistic patterns to those in the Voynich.

Should he succeed, Skinner will have solved a problem that has frustrated academics, cryptographers and computer programming experts since it was discovered in 1912 by the Polish collector Wilfrid Voynich.

Although there were allegations that Voynich had faked the book, the vellum and ink has been carbon dated to between 1404 and 1438. The authorship of the manuscript has led to heated debate with characters as varied as Dee and Leonardo da Vinci being posited as responsible for the manuscript.

Dee has also been suggested as a possible owner of the Voynich manuscript, a claim refuted by Skinner because the Tudor doctor and mystic was a notorious vandal of manuscripts that came into his hands. “The ladder-like symbol of his ownership is not on there and he hasn’t written anything on it,” he said, adding: “A temptation is always to find a name that everyone recognises, but I think it is unlikely to be by anyone famous.”

Skinner is hopeful that facsimiles of the manuscript will help decode it. “If it is in bookshops, someone might pick it up and recognise something in it that they are working with in another field of scholarship,” he said.

Asked what secrets he hopes it will reveal, he cited the medieval use of willow bark which provided the basis of aspirin: “It would be lovely if the herbalist section provided cures for things that we have forgotten about.”

- Watkins is publishing an edition of the book, The Voynich Manuscript, in August.

Since you’re here …

… we have a small favour to ask. More people are reading the Guardian than ever but advertising revenues across the media are falling fast. And unlike many news organisations, we haven’t put up a paywall – we want to keep our journalism as open as we can. So you can see why we need to ask for your help. The Guardian’s independent, investigative journalism takes a lot of time, money and hard work to produce. But we do it because we believe our perspective matters – because it might well be your perspective, too.

I appreciate there not being a paywall: it is more democratic for the media to be available for all and not a commodity to be purchased by a few. I’m happy to make a contribution so others with less means still have access to information.Thomasine F-R.

If everyone who reads our reporting, who likes it, helps to support it, our future would be much more secure.