The contemporary art exhibit, “Beyond the Age of Reason,” curated by Larry and Debby Kline, is nearing the end of its run at the San Diego Art Institute in Balboa Park. If you want to be intrigued, or even possibly enraged, by various artists’ visions of religion and spirituality, you’ll need to get to the museum space before the exhibit closes on October 31st.

I had the opportunity of being taken through the exhibit by the Klines. We stopped 21 times, sometime to look at a single piece, other times to take in related pieces in a group. The overall exhibition has approximately 50 art objects. I found myself highly interested in some objects, less interested in others. Readers who attend the exhibition may experience it in a completely different way, skipping over the objects that I found fascinating, pausing over the ones I skipped.

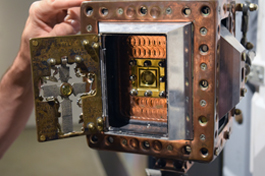

One of the most impactful pieces, for me at least, was a pinhole camera that also was a reliquary created by artist Wayne Martin Belger. The idea behind this camera is that we can look at modern day events and tragedies through the lens of the Holocaust. Within compartments of Belger’s camera is a yellow Jewish star, such as those that Jews were forced to wear in lands controlled by Adolf Hitler’s Nazi henchmen. In another compartment is a crucifix bearing the initials E.B., which stand for Eva Braun, who was Adolf Hitler’s mistress. The religious item once belonged to her.

In other compartments of the camera are other shocking items, such as body parts of Vietnamese combatants slain by American forces.

While a work of art in itself, the camera also is a working photographic device, and a room full of Belger’s photographs show such images as a Sioux Indian at the Standing Rock protest against plans to lay an oil pipeline from Canada; a guerrilla fighter in Chiapas, Mexico; a Syrian refugee on the Greek island of Lesbos, and a Palestinian refugee. These and other of Belger’s images at the San Diego Art Institute are scheduled to be seen next at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C.

Juxtaposing an item owned by Eva Braun, who loved one of the most evil men the world has known, with a Jewish star worn by a victim of the Holocaust, can prompt strong reactions. I found myself shuddering in revulsion, not at the art, but at the horrors these objects inside a camera body can force us to recall. If art, indeed, is intended to make us think, Belger certainly accomplished that objective.

So too did other pieces, whether they referenced Judaism, Christianity, Hinduism, Buddhism, paganism, or such practices as Voodoo and witchcraft.

As one walks through the exhibit, eventually reaching the room in which Belger’s camera and portraits are exhibited, various art pieces with Jewish-connected stories become apparent. For example, Scripps Hospital radiologist Dr. Steven Eilenberg, who is Jewish, has a piece there titled “Our Lady of the Bottle.” A small bottle sold to pilgrims in Lourdes, France, commemorating the vision of the Madonna experienced by Bernadette Soubirous, was the model for this larger than life size painting. Ellenberg, in a Latin-language legend surrounding the figure (and translated into English nearby) explained that he spent “several years undertaking an extensive restoration project. I burnished the cross, painted her toenails, made sure her crown was on tight. Her face was not her best feature so I swapped I out with Madonna’s from Edvard Munch. I topped her off with a golden halo and now here she stands before you, better than new, just without the power to heal…”

An ethereal, cloudy image seen behind glass is a woman with outspread arms. My neighbor Bob Lauritzen, who accompanied me on the tour, thought the image by artist Kristine Shomaker might be of a woman saying, “Lord, come and take me,” an analysis that Debby Kline promptly agreed with.

As in many examples of conceptual art, there could be more than one interpretation. From Larry Kline’s point of view, the figure is reminiscent of a woman who is bringing the light of Shabbat candles to herself. “The light filters through your fingers, so it is very spiritual, very ethereal.”

Nearby are two works by Eleanor Antin, another member of the Jewish community. One is a 1 ½-hour long silent film, The Man Without a World, set in a Jewish shtetl. The movie, which I unfortunately did not have time to watch, is shown in a small viewing room off the main exhibit hall. “The movie is about Jewish culture,” Debby Kline informed. “It talks about someone getting married, cutting their hair, and how the man can’t see the woman.” In the main exhibit space in an Eleanor Antin photograph that appears at first glance to be a painting, titled “The Sad Song of Columbine.” In this painting a woman is on a funeral pyre, and a robed man sits brooding in the foreground. Seemingly oblivious to their surroundings, a young couple is cavorting off to the side.

“We used this as the title image for ‘Beyond the Age of Reason’ because this is one where the narrative is not really clear,” commented Larry Kline. “There are a lot of symbolic things, but you have to make out for yourself what is there.”

Another Jewish artist whose work is on display is Erika Rothenberg, whose background is advertising. At first glance, you might think this is an ordinary signboard, perhaps listing talks to be given in association with the exhibition. But in fact, it is an artistic commentary on modern society. According to this signboard, at 7 p.m., on consecutive nights from Monday through Saturday, there will be discussions about teen suicide, addictions, battered spouses, post traumatic stress disorder, joblessness, soup kitchens, to be followed on Sunday by a sermon on “America, the Greatest Nation on Earth.”

Nearby are images by Jewish artist Scott Forschauer, who is deeply interested in Voodoo. The Klines explained that in this practice, one can create a design known as a veve, which can help to summon Papa Legba, who serves as a conduit between a person and the spirit world. “In Voodoo,” said Larry, “they will use all kinds of things to create these images. Sometimes it’s corn meal, sometimes sage, sometimes gunpowder.” Froschauer cuts molds into wood, “fills them with gunpowder and sage and other materials, lights them on fire, and then presses this (a press device) down.”

Someone just passing the exhibit, without taking time to read the legend, might think the Voodoo drawings were French wallpaper, Larry said.

Artist Paula Levine took Bibles—Jewish and Christian—and turned them into pulp, and then canned them under pressure. Except for their labels, the two grayish Testaments in this format are indistinguishable. “The first thing I noticed was how similar they are,” Debby said. “Everyone says religion is black or white, right or wrong, and they never talk about the gray areas in between. Yet, when they are put under pressure they are reduced to this gray substance.”

I had seen another set of Levine’s images in 2015 when the Gotthelf Gallery at the Lawrence Family JCC hosted the Kline-curated exhibition titled “Seeing is Believing: A Reinvention of Articles of Faith.” The set at the San Diego Art Institute included numerous images of Scriptures crumpled into different shapes, as if they were Rorschach tests. In one image, neighbor Bob saw a set of lungs; in another, I saw what looked like chicken fillets on a barbecue.

“How many sects are there of Judaism, or Christianity, and the thing is that they are all reading the same text, yet disagreeing what the text actually means,” said Larry. The disagreements can continue even over the images.

Have you ever heard of a Jerusalem cricket? Wikipedia reports the insect is neither a cricket nor indigenous to Jerusalem, but nevertheless the name has stuck. It’s also called a potato bug, which also is a misnomer according to Wikipedia. It is one of several exhibited sculptures created in the studio of Einar and Jamex De La Torre, whose works often combine images from the pre-Columbian era, with various modern objects, such as little toys, and dolls, poker chips and dice.

Maria Munroe creates works of art that serve as highly stylized urns for cremated remains. One silver piece in the exhibit contains the ashes of a man who headed the silver department for Christies; while another, fashioned from crystal, is the reliquary for remains of the artist Elizabeth Franzheim.

Imagine, an artist becomes, herself, a piece of art.

Republished from San Diego Jewish World