For the month of February, writer Antwaun Sargent was invited to explore works of art in the Jewish Museum collection that celebrate the intersection of black and Jewish experience. The series continues with Photo League photographer Alexander Alland’s Ethiopian Hebrews Series.

Alexander Alland’s Ethiopian Hebrews (c.1940) is a series of photographs in the Jewish Museum collection that documents the interior lives of a community of black Jewish people in Harlem. Alland, a first generation Jewish-American immigrant, was a member of the New York Photo League, an organization of leftist artists formed in Manhattan in 1936. The Photo League used the camera to capture the city and its residents in images that could reinforce calls for social reform.

In 2011, I saw The Radical Camera: New York’s Photo League 1936–1951, the Jewish Museum’s extraordinary survey of the organization’s pictures. It was from that exhibition that I discovered the Harlem Document, a group photography project that was meant to showcase the postwar social decay of the black uptown community. The project lasted four years, producing an array of images from 1936 to 1940, documenting the lives of the community’s poor; images include project leader Aaron Siskind’s Backyard, an aerial view of a yard filled with trash. Although the anticipated photo-book was never published, the photographs were exhibited in New York and reproduced in the nationally-circulated Look magazine, with captions that emphasized — and even embellished — the degree of poverty and decay seen in the images.

The project photographers were heavily criticized for their vernacular pictures of Harlem. The community commonly called the “black mecca,” where a renaissance in art, literature, and life had occurred a decade earlier, was largely missing from the Harlem Document. “Our study was definitely distorted,” Siskind later reflected. “We didn’t give a complete picture of Harlem. There were a lot of wonderful things going on in Harlem. And we never showed most of those.”

Unlike the Harlem Document, Alland’s Ethiopian Hebrews Series are not poverty pictures. Rather, they focus on the upstanding members of a religious community in an attempt to advocate for so-called “model immigrants.” First produced for Life magazine and juxtaposed with images of Russian Gypsies on the Lower East Side, these photographs were part of Alland’s larger project to document the city’s many ethnic groups. Selections from the Ethiopian Hebrews Series were later published in his book American Counterpoint (1943). This comprehensive volume was dedicated to America’s immigrants and their descendants, and opened with a quote from Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass: “All races are here, / All the lands of the earth/make contributions here.” The images stand as a reminder that no matter how foreign the subjects may seem, they are not so different from the (presumably white) viewer after all — that America is, at heart, a nation of immigrants.

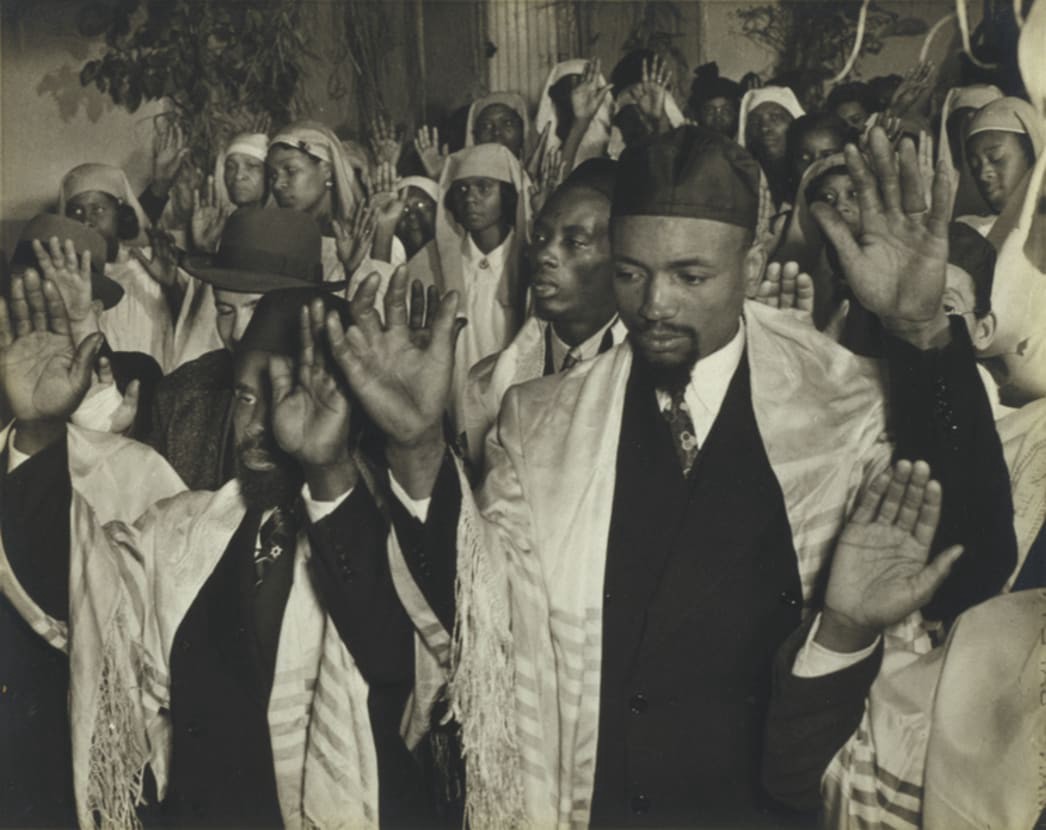

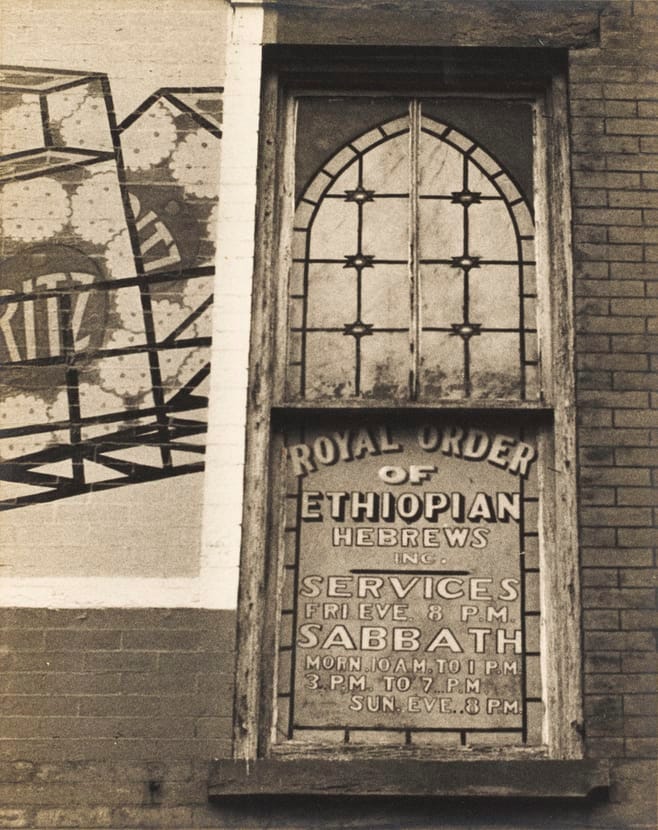

Alland’s series features images of Harlem’s African-American Hebrews, a denomination believing that they descended from Ethiopian Falashas (Ethiopians of Jewish faith). His photographs capture their vibrant displays of tradition, faith, and self-determination. Ethiopian Hebrews Series, №27, a black-and-white photograph of a group of black Jewish men and women, traditionally robed with their hands up in prayer in a synagogue, is an image of deep spirituality and community, contrasting the impressions of systemic poverty in the Harlem Document. The images Ethiopian Hebrews Series, №1, a picture Alland took of a sign outside of a community synagogue that reads “Royal Order of Ethiopian Hebrews Inc.,” and Ethiopian Hebrews Series, №37, a shot of school children reading Hebrew, captures how the community saw themselves as a god-fearing, striving people.

Alland’s pictures reveal a dynamism that recalls the images of Harlem life, which black postwar photographers such as James Van Der Zee, Roy DeCarava, and Gordon Parks also captured in the neighborhood. Their images, like Alland’s Ethiopian Hebrews Series, resist easy stereotypes to show a fuller depiction of Harlem that offer up another side of the history that sits at the intersections of Jewish and black identity, as well as religious tradition. It’s the story of a community within a community, a history within a history.

— Antwaun Sargent, Guest Contributor