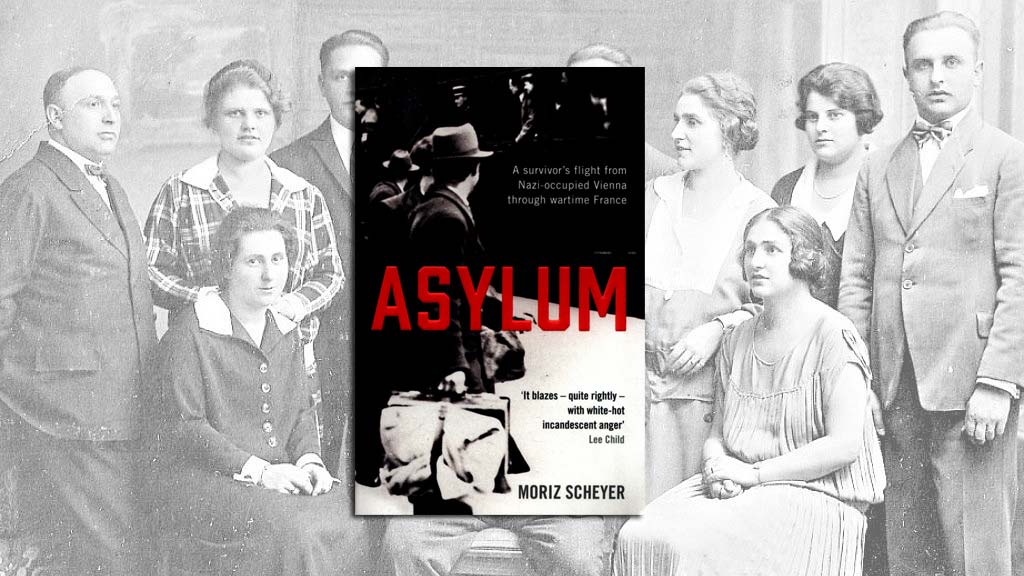

Written at the time of the actual events, this powerful book starts by describing the atmosphere in Vienna before the Anschluss by Nazi Germany, followed by the author’s flight, together with his wife and non-Jewish housekeeper, who was also nanny to their children and his wife’s best friend (and who insisted on remaining with them throughout their ordeal).

Moriz Scheyer was a well-known and respected journalist and writer in pre-war Vienna. The editor of the arts section of the Neues Wiener Tagblatt, he was a friend or acquaintance of many prominent writers and musicians of the time, among them Stefan Zweig, Bruno Walter and Arthur Schnitzler.

As was the case with countless Jewish families, their comfortable bourgeois way of life was disrupted by the imposition of Nazi restrictions and race laws. He describes the behavior of the general population of Vienna with bitter scorn, favorably mentioning just one or two individuals (a waitress in a café he frequented, a compositor for his journal) who showed any fellow-feeling towards him.

In search of security, Scheyer moved first to Switzerland, then to his beloved Paris (their two teenage sons had found sponsors in the UK), and the trio survived there until the Germans overran France too. When the country was divided into two zones, one occupied by the Germans and the other supposedly ‘free’ under Petain, ruling from Vichy, thousands of Parisians set out to leave the city. Scheyer describes the ‘Exodus’ in vivid terms, as well as the indifference displayed by most French people to the suffering of their Jewish compatriots, their desire not to be bothered by any accounts of personal misery, and their focus on continuing to enjoy the good things of life.

The Scheyers also left Paris, but their attempt to find refuge in the French countryside failed, and they returned to the capital, only to find themselves being harassed by visits from gendarmes and confiscation of what little property they had. Scheyer describes the systematic way the Nazis looted, stole and profited from the property of persecuted Jews, and does not spare the French who cooperated in these acts. The trio lived in a state of constant anxiety until they heard the fateful knock on the door heralding the arrest of Moriz.

Together with several hundred other men, Scheyer was taken under guard to the concentration camp of Beaune-la-Rolande in the Loiret region, and assigned a bunk in a hut containing 180 men. Conditions in the camp were atrocious, starvation rations and daily humiliations were the rule, accompanied by the senseless brutality of their guards, both French and German. What little consolation there was came from the sense of comradeship shown by other denizens of the hut. Scheyer describes all this in searing detail, and it is without a doubt accurate. It is harrowing to read.

On the eve of the transportation of the inmates of the camp to Auschwitz, Scheyer was told to report the next day to the camp adjutant’s office with his bundle of possessions. Twenty of the camp’s 1,800 inmates who were over 55 years of age or physically disabled were lined up, closely examined, harangued by the commandant, then marched under escort out of the camp to the town center, where they were released. Scheyer was able to board the bus from Orleans to Paris, and was greeted with shrieks by his wife and Slava her friend when he turned up on the doorstep of their apartment.

In a chapter entitled ‘Another stay of execution,’ Scheyer describes how, after a brief respite at home, the entire neighborhood was sealed off and the hunt for Jews began. It was known that those who were caught were sent to the infamous camp at Drancy. Scheyer and the two women managed to evade the net, and tried to get to the Free Zone. The vicissitudes of that attempt at escape are again described in disturbing detail, specifying the amounts paid to passeurs and sundry officials who were supposed to help the trio get to safety in Switzerland, the fraudulent assurances of assistance and several hair-raising close escapes as the danger of exposure came ever closer. This attempt failed too, and they turned back into France, ending up in a small town called Belvès in the Dordogne region. From there they were summoned to Grenoble and kept under guard in an army barracks together with several hundred other Jews. While there, Scheyer suffered a heart attack, and the French doctor who attended him gave him a document stating that because of his medical condition he was unable to travel. The guards told Scheyer to leave the place immediately, and he managed to do so only by being physically supported by his wife and Slava. The next day all the detained Jews – men, women and children—were sent to Auschwitz.

The trio returned to the town of Belvès, where they were obliged to register and were subject to ‘friendly’ visits from local gendarmes. One of Scheyer’s acquaintances, a young man named Jacques Rispal who lived there with his parents, showed sympathy for his plight. His mother, Helène, woke up one night with an inspiration about where Scheyer, his wife and Slava could be hidden. Thus it was that the trio were smuggled into a convent, ‘Asile de Labarde,’ an isolated building on a nearby hilltop where the nuns looked after mentally and physically disabled women.

For the next two years the trio were able to live there in relative safety. Scheyer describes the selflessness and piety of the nuns and the unexpected kindness of the Rispal family in terms that convey the depth of his gratitude and emotional attachment to them. Life in the convent was Spartan but the Scheyers were finally able to breathe more easily, without feeling as if they were hunted animals. The gift of a radio, smuggled to them by the Rispals, enabled them to hear news from the outside world and, perhaps even more significantly, to listen to music again. Scheyer describes the experience as being “like a blessed release of the self…” reminding him of the concerts he had heard in Vienna.

In comparing the situation of Jews at that time to that of the ‘weakminded’ inmates of the asylum he writes: “We, on the other hand…are hunted animals… If Einstein were here, he would be a hunted animal…” and the same would apply to a Bruno Walter, a Franz Werfel, even the great Gustav Mahler if he were still alive. These thoughts lead him to mourn the fate of the millions of Jews, adults and children, who were ‘eliminated as pests’ by the Germans, and among whom there had undoubtedly been countless gifted human beings in any and every sphere of human endeavor [as was indeed the case, DS].

The Scheyers survived the war and settled in Belvès. After Moriz’s death in 1945 the typescript of his memoirs was thrown away by his son, who considered the writing too intense in its condemnation of and hatred for the Germans. By chance, however, some years later their grandson came across the carbon copy, rescued it and translated it. He has annotated the text, as well as adding an introduction, epilogue, biography of the author and index of people mentioned in the text. He has done an admirable job, and we owe him a great debt of gratitude for providing us with this harrowing yet gripping account of events as they occurred in real time. The text uses language which is eloquent without being flowery to convey the soul-destroying experience of living through that horrific period in human history.

Republished form San Diego Jewish World