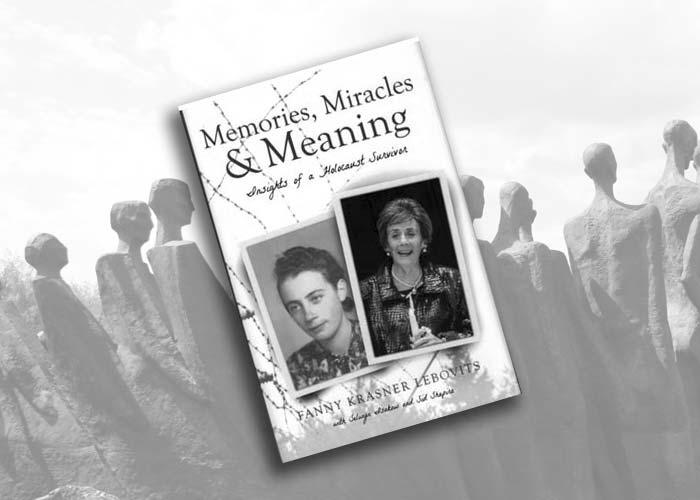

At 96, Fanny Krasner Lebovits is still going strong. I saw her as recently as December 2nd in attendance at a regional meeting of her beloved Hadassah, an organization to which she has devoted a large portion of her life. She had been program chair and then president of what formerly was called the San Diego chapter of Hadassah, and later moved up to become president of the entire Southwest Region of Hadassah. She visited the Hadassah Hospital in Jerusalem on each of her 35 trips to Israel and has attended more than 30 national conventions of the organization. Other people thinking about service to the Jewish community might content themselves with such a record, but not her. She also is involved in the Maccabi organization, Hebrew Home, Congregation Beth El, South African Jewish American Committee (SAJAC), New Life Club, and the Jewish Community Relations Council.

All this activity, along with her every Friday night Shabbat dinner tradition as the matriarch of her large family, represented just the third stage of her life—her American period.

Europe was the first stage for her life. She was born as Feiga-Chase “Fanny” Judelowitz on October 27, 1922 in the port city of Libau, Latvia; survived the Holocaust against impossible odds; and worked with the World Jewish Congress in Stockholm, Sweden, to influence diplomats to vote at the United Nations for the partition of Palestine (and the creation of Israel). During that first stage of her life, she married and was widowed by Monya Kaganski, who had served as the humane head of Libau’s Jewish Council. Typhus claimed his life, a short time before liberation.

Africa was the second stage and continent of her life. She lived in Johannesburg, South Africa, where her second husband, Louis Krasner, built up a successful jewelry business, teaching the craft to his son Harold, who brought it to San Diego. But nine months after Fanny and Louis followed their son to California, Louis died of a heart attack, again leaving Fanny as a widow.

More than two years later, Morrie Lebovits proposed marriage in 1982 to Fanny over a dinner to celebrate her 60th birthday at the Westgate Hotel in downtown San Diego. They spent nearly 14 years together until he died of cancer. Thrice married, thrice widowed, Fanny remains an active presence on the San Diego scene, lecturing and now having written about her experiences in the Holocaust. Some four score of her extended family were murdered by the Nazis, including her parents, Herman and Sarah, and little sister, Liebele.

We are achingly familiar with the Nazis’ process of dehumanizing, ghettoizing, transporting, selecting, gassing, and burning, or for the luckier few selecting, starving, and forced laboring. Along with her young sister, Jenny, Fanny was in that second group, brutalized, sickened, but managing nevertheless to survive. Fanny had training as a nurse, which led to her being assigned by camp commanders to rudely equipped infirmaries, where without proper bandages, medicine, or equipment, she tended to the ill. It was a grueling assignment, with many frustrations, but it kept her alive, and in a position to keep her sister alive as well.

Some incidents in Fanny’s life during the Holocaust were particularly memorable and heart-breaking. At the Kaiserwald Concentration Camp, near Riga, Latvia, Liebele, then 8, was put in one line (the one marked for death) and her mother, Fanny, and Jenny were put in another. Their mother ran to join Leibele in the other line. “I can’t let my little Liebele go by herself. You two can look after yourselves. Fanny, look after Jenny.” And that was the last they saw of her. “My mother always put others first,” commented Fanny. “There isn’t a day that I don’t think about my mother’s selfless act.”

Whenever prisoners were taken from the concentration camp to work venues, or trains, they were required to sing German songs and to smile. “Otherwise they would hit us with a stick,” Fanny wrote. “While music was and still is a passion of mine, the forced singing cut through me like a knife and continues to haunt me.”

Fanny and Jenny were ordered to clean the apartment of some non-commissioned officers, and each time they did so, “we found bread wrapped in newspaper left for us in the wastebasket,” Fanny said. “It was this bread that fortified and sustained us. Feeding inmates was strictly prohibited and this act of kindness by the Feldwebels could have resulted in serious consequences for all of us, including being shot … Not all people are evil. I never believed that all people were evil. …”

When Fanny moved from Europe to South Africa, on the invitation of her future husband Louis, she was greeted by him, his sister-in-law Jean, and by a black assistant named Steve, who would carry her luggage. “I reached out to shake Louis’s and Jean’s hands. Jean looked on disapprovingly as I also shook Steve’s hand. Later I asked Louis about Jean’s reaction at the airport. ‘White women don’t touch black men in South Africa,’ Louis explained. I burst into tears. I had just lived through discrimination and persecution at its worst, and now this!”

She later berated herself for not having more strenuously protested apartheid, nor speaking up for the human rights of South Africa’s majority black population. “We didn’t speak out because it was politically dangerous,” she said. “We just wanted to get on with life.”

In the United States, she decided, she would not recuse herself from the fight for justice. “I sometimes feel I have been surrounded by hate and so now feel compelled to speak out while I can.”

There are many more anecdotes and thoughts to ponder in this compelling memoir. I’d like to close this review with two. Fanny once received a call from a woman in Atlanta, whose daughter had asked to be “twinned” with a girl who died in the Holocaust. Through a program called “Remember Us: The Holocaust B’nai Mitzvah Project,” she learned about and chose Fanny’s sister, Liebele. The Yad Vashem Memorial Museum in Jerusalem informed her that Liebele had sisters, and through research, the Atlanta girl found Fanny, who later wrote: “And it came to be that more than seventy years after her cruel death, little Liebele Judelowitz was symbolically recognized, honored, and celebrated as a bat mitzvah in Atlanta, Georgia, United States of America, land of the free and home of the brave.”

Years later, Fannie’s own granddaughter, Lauri First Metross, was visiting the Holocaust Museum in Washington D.C., where you can pick a “passport” of someone who went through the Holocaust, and step by step, learn that person’s fate. Lauri reached into a basket and pulled out Fannie’s ID card, which contained information gleaned from an interview Fannie had given to museum officials year before. Unfamiliar with the surname Judelowitz, but recognizing the story, Lori telephoned her mother and reported, “I’m shaking right now… I think I picked up Granny’s passport.” Her mother, Shirley (Krasner) First, told her. “Because you picked up your grandmother’s passport, it means you have an obligation to teach your children about the Holocaust and they have the obligation to teach their children about the Holocaust and so on and so on. That’s why you picked up her passport.”

Republished from San Diego Jewish World