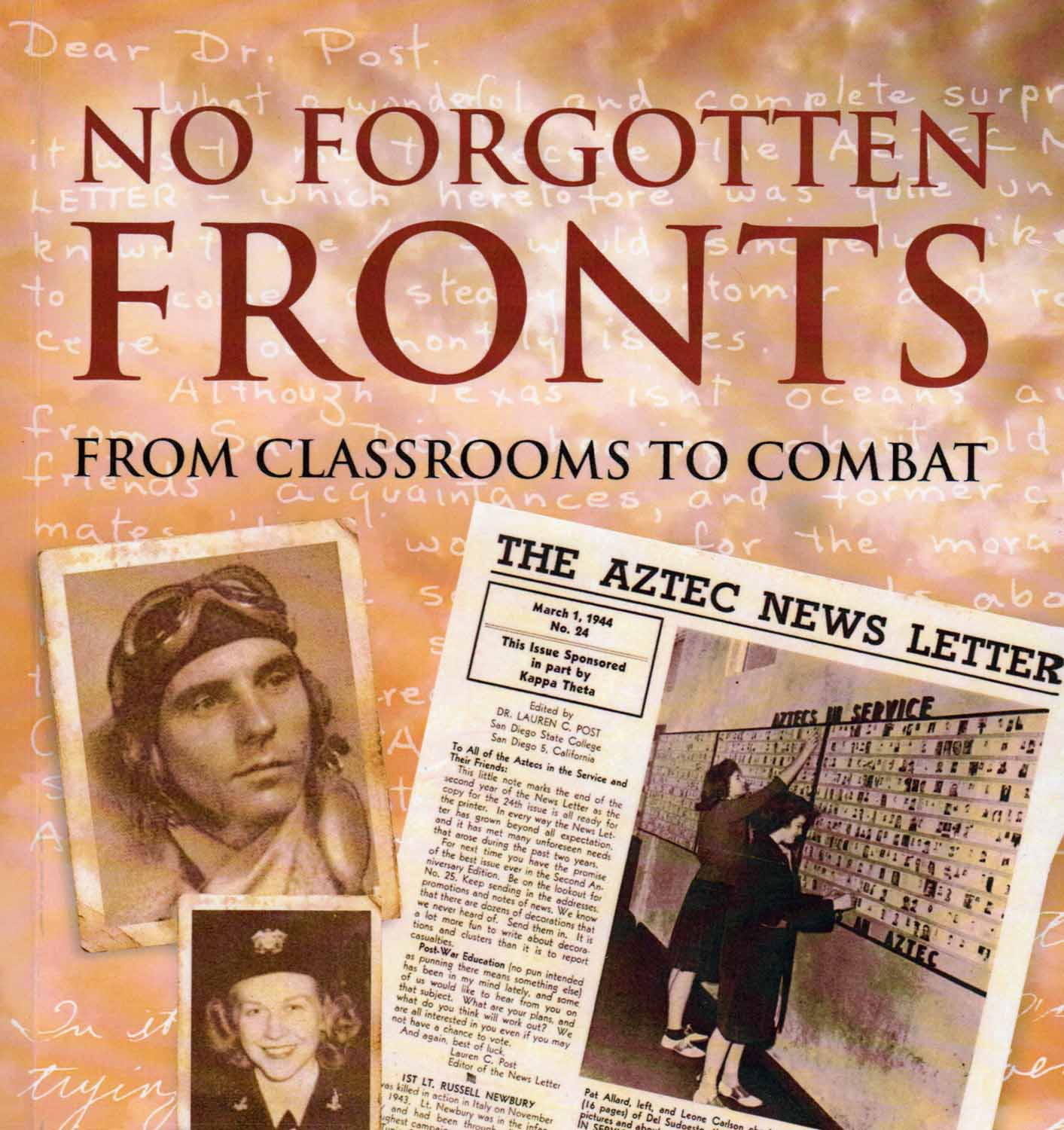

During World War II, many people turned to The Washington Post for their news. On the other hand, G.I.’s who were former San Diego State College students turned to Prof. Lauren C. Post.

“Doc” Post, a professor of geography at SDSU, for four years published a monthly news letter containing letters from former “Aztecs” who were serving in the war. Scrupulously mailing the news letter out to America’s soldiers, sailors, Marines, and flyers, Post brought them news of their college friends such as who was serving where, who had been injured, or taken prisoner, or was killed. Packaged with tidbits of news and photos from the campus, Post’s news letter was greatly appreciated by the GI’s overseas as well as by their families at home.

Post said that his “recollection of standing watch on a destroyer in 1918 made me visualize the need of getting news to our men who are in this war–something to think about as they gaze into the blackness hour after hour.” In fact, it did far more than that. Wally McAnulty was serving in the Pacific Theatre when he learned in the news letter that his brother, Ernie, had been captured by the Germans and was now a POW.

Author Lisa Shapiro combined short descriptions of the war’s progress with the letters in order to provide context for readers of this remarkably valuable volume. Collating the letters from the fronts at times were an emotional experience for her. “My heart ached when I read paratrooper Herman Addleson’s description of the Statue of Liberty as his ship sailed out of New York, and I wept when I learned that he died on D-Day in Normandy,” she wrote.

Addleson was among several Jews whose letters are included in the book, with another being Al Slayen, who survived and returned to San Diego. In one letter to Post, Addleson wrote from Fort Benning, Georgia, what it was like to make a first jump as a paratrooper:

…As we stepped in the plane & sat down, buckled ourself to the seats, everyone was joking & trying to sing. Before we knew it the plane went down the runway & we were looking at the ground disappear beneath our feet. There’s a fellow called the “jump master” who gives the orders. When we were at 1200 ft., everyone trying to cheer-up everyone else, the jump-master’s voice sounded like some immortal soul. “Get Ready,” he hollered. At this point every man turned white, or all colors. Yes, the big ones, tough ones, officers & soldiers were scared. A pin could be heard, that’s how still it became. Only the roar of the motors. The next commands came very fast. “Stand up,” every one of us managed to stand and grab the cable above our head. “Hook up, Check Equipment,” & “Sound Off,” were all done automatic. Then “Stand in the Door,” everyone fixes his eyes on the door. The jump-master taps the first man & “go.” Out we go, & when you leave the door the prop-blast takes you away. You drop 75 ft. to 100 ft. before your chute opens. In that time, you don’t know you’re falling. When you hear a crack of a whip sound, & you look up & there is most beautiful sight in the world. The Canopy is open & all is fine. You descend about 19-20 ft. per second so you are down before you know it. After you’re on the ground, the tension over, you holler with joy & slap each other on the back….

After Addleson shipped out to an uncertain fate from New York, he described his feelings:

From the “Staten Island Ferry” to the boat, was something to witness. First, we joked and kidded as we passed familiar signs along the harbor like “Maxwell House Coffee,” “Bethlehem Steel,” “Colgate Soap & Perfume” & then that thing that stopped the crowd, the “Statue of Liberty.” Tough guys had tears in their eyes, many stood gazing open-mouth, many a heart was in one’s mouth, with a feeling of emptiness in one’s pit of the stomach. The Statue of Liberty was beautiful & as she disappeared Long Island came into view, then Brooklyn & what memories & laughs we all had. Then as some giant hand pushing us way out, land seemed far off, New York skyline seemed to diminish. When that disappeared & possibilities of seeing land of U.S. was gone, we just leaned back & silence was a bliss as we all thought of what we left behind & what we are fighting for.

Slayen, who was a lieutenant, was also a sightseer. From a location in North Africa that he could not name because of censorship rules, he wrote in April 1943:

The weather here is grand – It is a little better than you will find in San Diego—many of the buildings are really beautiful. Here in town we have French and people from the continent. On the outskirts of town live the Arabs… They do add color to the scenery with their flowing robes and assorted modes of transportation. There is a continual clashing of the old & new worlds. The Arabs seem to come out of the past into an ultra-modern city—most of them barefooted riding on donkeys loaded down with tremendous loads… I have seen donkeys hitched up with camels pulling wooden plows…

Gi letter writers often found relief in humor, whatever their circumstances. From somewhere in the South Pacific, PFC Jack Chandler wrote, “A lot of new mosquito stories have come out lately. Yesterday, for example, we heard of a large one that landed on the airfield. He was gassed up and loaded with bombs before the ground crew discovered that it wasn’t a B-17.” Following the Battle of Saipan, Perry de Long wrote about a proposed post-war get-together, “I’ll be happy to toot a horn at that reunion Doc. Though for a while I thought it was going to be strictly duets between Gabriel and me.” Bernie Carroll, writing from Caserta, Italy, in 1945 advised Doc. Post that “yours truly has been promoted. It was really quite an occasion, as it came at 4:30 p.m. on 7 May 1945 and at 5:20 pm. that day we received word that Germany had surrendered unconditionally. I guest that my being promoted was too much for the Krauts.”

After the Allies defeated the Germans, other U.S. servicemen and women continued to fight in the Pacific Theatre, sometimes worried that in the euphoria over the defeat of Nazism, people back home might forget that they were still fighting the Japanese. Doc. Post assured them that there were no forgotten fronts – which inspired Shapiro’s title for her book.

In the April 1945 edition of the newsletter, Post provided these statistics: Grand total Aztecs in service 2,800; Women in service 135; Discharged, mostly on medicals 75; Prisoners of war 30, Missing in action 25; Wounded in action 72; Killed in action and training 82; Decorated 216; Commissioned officers 1,200; Aztecs overseas 1,200.

From the Doolittle raids over Tokyo at the beginning of the war to progress in Europe, through Japan’s surrender, and occupation duty in both theaters following the war, San Diego State College students were writing letters to Dr. Post, and also sending him wartime souvenirs – a collection that is now housed at SDSU’s Love Library. Many of these correspondents signed off their letters “Aztecs Always.”

Republished from San Diego Jewish World