If I understand author Edmund Case’s basic premise, it is if people “do Jewish,” then for all practical purposes, they are members of the Jewish community and ought to be recognized and treated as such.

If we take the position that those who want to marry one of us become one of us, then we can grow the Jewish community, strengthening it with bonds of love. A couple that is warmly accepted in the community, without qualification, is likely to engage with it wholeheartedly, and to incorporate more and more Jewish behaviors into their home. Doing one Jewish activity may lead to another: They might want to draw up a ketubah, be married under a chuppah, have the groom break the glass under his foot, and then dance the hora at their wedding reception. They may decide to attend some services at their neighborhood synagogue. They might begin to light candles on Friday nights, say blessings over wine and bread; incorporate such celebratory Jewish holidays as Purim, Passover, and Chanukah into their lives; decide to have a brit milah for a newborn son, or a baby naming for a daughter; enroll their children in Jewish pre-school, and encourage the children to study for b’nai mitzvah.

All that, regardless of whether one of the partners actively or passively identifies with another religion. It’s possible that with familiarity with Judaism, whatever reservations the partner from a different religion may have had about converting to Judaism may be allayed. Such was the case in Case’s own marriage to a Christian woman after 30 years of marriage.

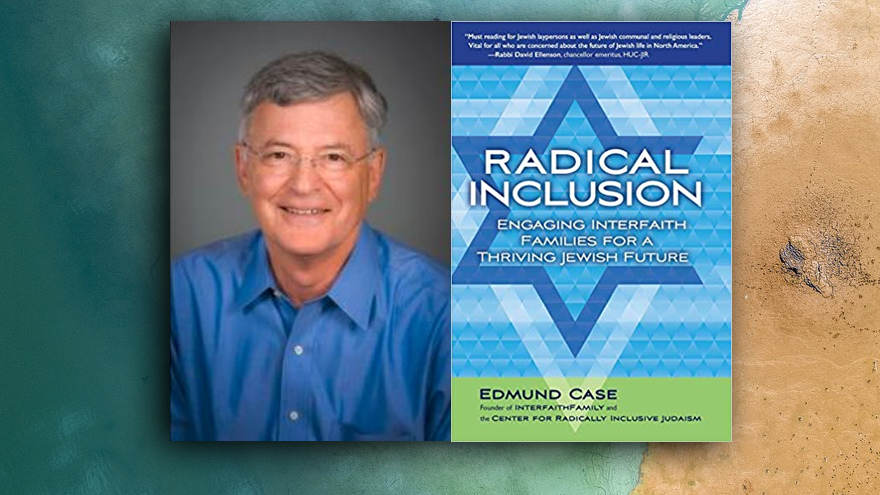

On the other hand, according to Case, if we actively seek to discourage inter-marriage, we send the message that we do not consider the partners in that marriage to be worthy of our community. In essence, we are giving them an incentive to seek acceptance elsewhere. Case, who is the founder of the Center for Radically Inclusive Judaism, understands why some streams of Judaism have traditionally rejected inter-marriage. He knows that rabbis from these streams believe that by performing intermarriages, they might be seen as encouraging them, which in turn may lead to fewer marriages in which both partners are Jewish. Ultimately, the concern of those rabbis is that marriages between two Jews are more likely to produce Jewish children than otherwise.

As one might expect, Case disputes this. Judaism is a 3,500-year-old religion that teaches important ethical values to which many people may subscribe, regardless of what religion they were born into. If inter-married couples have not been raising their children Jewish, it may not be the inevitable result of such marriages. Perhaps it is because the Jewish community seems to be hostile rather than welcoming to them.

Have you ever seen billboards and bumper stickers that say “Put Christ back into Christmas”? This is the lament of religious Christians who believe that the holiday has become over-commercialized and secularized, with Santa Claus and his elves replacing Jesus and his disciples as the main focus. What worries religious Christians ought to reassure those Jews who are afraid exposure to Christmas trees and presents will turn children of an inter-marriage away from Judaism. Such celebrations, Case argues, are akin to the celebration of Thanksgiving – a happy time with little or no impact on the children’s overall belief system. So, he suggests, Jews in inter-marriages should not fret if their partners want a Christmas tree. It’s a reminder of happy family times, rather than a religious statement.

Case may have a good point, but I’m troubled by this question: If we believe that if people “do Jewish” they will become, increment by increment, part of the Jewish community, is it not also true that people who “do Christian” will likewise be drawn bit by bit into the Christian community? Can we really have it both ways?

Republished from San Diego Jewish World