A 12-branch copper candelabra kindled on holidays by Jews in 18th-century Italy. Sheets of prayers handwritten in Hebrew by an unknown scribe in 15th-century Spain. An oven for baking matzah from 19th-century Portugal. A Passover Haggadah in Hebrew and Arabic from 18th-century Iraq, transported to India where it was discovered more than 300 years later.

These are among the thousands of treasures from the Jewish past that Rabbi Eliahu Birnbaum has collected over the last 22 years. Treasures he’s discovered while mentoring the rabbis and teachers the outreach and education organization Ohr Torah Stone (OTS) has dispatched to Jewish communities around the globe.

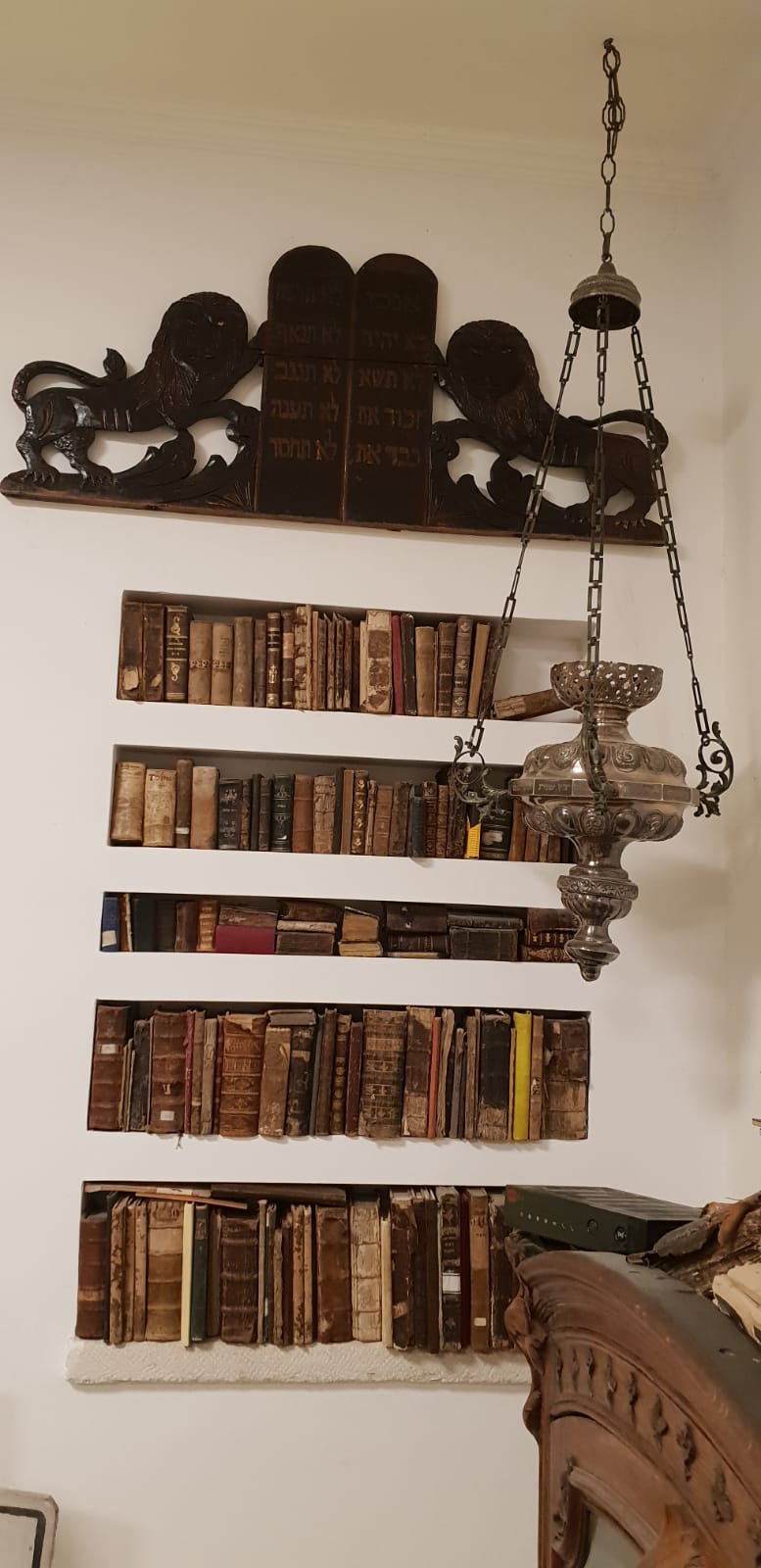

The rabbi’s office in Ohr Torah Stone’s headquarters in Efrat, Israel, in addition to his walls and shelves at home, are a virtual tour of Jewish history around the world, including objects from India, Poland, Egypt, Romania, Greece, Turkey, Russia, Uganda, Jamaica, Georgia, Singapore, Ethiopia, New Zealand, Italy, Morocco, Poland, Tunisia, Portugal and Uruguay, too.

Take the matzah oven, for instance. Covered with common roofing tiles, it was ingeniously designed to camouflage its function during a time when celebrating a Jewish holiday would easily have gotten Portuguese Jews into serious trouble with the authorities. An unexpected bonus came with this gift from an old Jewish family there: A box of 70-year-old matzah from the last time it was used.

When he arrives in a community to work with the OTS rabbis and teachers there, sooner or later, Birnbaum slips into detective mode. “Yes, we have a geniza, but it’s nothing important,” he’s been told numerous times. “But I’ve found amazing old books, prayers, Haggadahs and more in those places.”

No wonder Rabbi Birnbaum’s been called the Jewish Indiana Jones.

Though possessing the soul of a collector, Birnbaum’s life’s work is actually as a collector of Jewish souls. Indeed, his gathering of bits and pieces of Jewish history is a natural outgrowth of his travels as director of OTS’ Straus-Amiel and Beren-Amiel Emissary Program.

“Committed to the rejuvenation and cultivation of world Jewish community” through the training and placing of rabbis and educators to serve communities on virtually every continent, the program has 277 emissaries in 300 communities in all. And it keeps the rabbi on the road more than half the year (in pre-coronavirus times) to support these young (mostly Israeli-born) emissaries.

Taking Torah on the road

Born into a strongly Zionistic community in Uruguay soon after his bar mitzvah in 1972, Birnbaum made aliyah by himself, living with a cousin until his parents and sister arrived two years afterwards. A dozen years later, he’d earned his rabbinical degree from Har Etzion Yeshiva, eventually becoming chief rabbi of his native Uruguay.

It was there that he took a walk with a visitor—OTS founder Rabbi Shlomo Riskin—one that was destined to change Birnbaum’s life. The year was 1996.

“I saw how knowledgeable and charismatic he was—a natural for outreach,” recalls Riskin. “The Lubavitcher Rebbe had told me, ‘Your new empire in Efrat will last until the coming of the Moshiach on the condition that you send out Israeli emissaries of Torah all over the world, as Isaiah teaches, ‘Because from Zion Torah will come forth.’ As soon as I met Rabbi Birnbaum, I knew he was the one to lead this.”

On their walk, Birnbaum said he had also been wondering how to replicate what he was doing in Uruguay all over the world. “And I told him that’s exactly what I want him to do for OTS,” says Riskin. “To see to it that Jews throughout the world would appreciate their beautiful tradition and their amazing history.”

More than 20 years after that fateful walk, 277 OTS rabbis and teachers, in partnership with their spouses, work with communities on nearly every continent.

Eliran Shabo is one such rabbi. Last year, the Jerusalem native, his wife and their children were sent to Athens, Greece. “When my family and I arrived in this warm and welcoming community, we soon learned about its rich past and traditions that had almost disappeared from the world,” he says. “Romaniot Jews [emigrating to Greece and Rome following the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 C.E.] have customs that are more than 2,000 years old—sometimes in the community’s Jewish institutions, I feel like I’m in a living museum.”

OTS president Rabbi Kenneth Brander, who came on board following Riskin’s retirement in 2018, says he’s been impressed with Birnbaum’s devotion to the OTS communities and the young leaders sent to enrich them.

“For decades, he’s helped people in hundreds of communities around the world to know and own their Jewish story,” says Brander. “Our emissaries, who speak 24 different languages, touch the lives of hundreds of thousands of people each year with each community having its own history and traditions and its own challenges.”

The rabbis help community members untangle such dilemmas as to how to bury loved ones in accordance with Jewish law in countries where the authorities insist on cremation. “Our rabbis are called upon to be spiritual leaders no matter how young they are,” reports Birnbaum. “The million-dollar question is how to keep Jewish momentum going in these communities today, especially with COVID keeping everyone apart.”

And, while most of the people Birnbaum spends time with around the world are Jewish, others he visits have no halachic claim but nonetheless trace their roots deep in the Jewish past, often believing that they are descended from the 10 lost tribes.

“We’re still connected with them,” he says. “And we need to respect and appreciate them.”

The power of the object

Indeed, Birnbaum will tell you that his collection of ancient Jewish artifacts serves two interlocking purposes. “By learning about the past from them, we both raise the pride of the Jews there with their long and beautiful history, and we raise the awareness of Jews everywhere that the Jewish people survived and even thrived in virtually every corner of the world.”

To Chaviva Levin, a senior lecturer in Jewish history at Yeshiva University in New York, rescuing and sharing these ancient Jewish treasures unleashes an irreplaceable power showing what it felt like to be Jewish over the generations and around the world.

“It’s the simple act of connecting with something a Jew touched so long ago,” she says. “Through them, we can sense their relationship with their culture, with their people, showing us that they are so different from us and yet we’re so connected—so strange and so familiar at the same time.”

As Brander puts it: “Each of these found objects is a portal to celebrate our people and empower Jews everywhere to know our own story.”

Now that they’re brought together in the Jewish homeland, Birnbaum says he’s looking to use these resources from the Jewish past to open the eyes, minds and hearts of today’s Jews. Towards that end, he’s hoping to open a museum for visitors to experience what he calls “the multi-colored story of Jewish life around the globe.”

But these days, the 62-year-old Birnbaum, like so many others, has been benched by COVID-19, allowing him to spend more time at home in Israel with his wife, four grown daughters and their families. Yet, he says, he misses spending time with these far-flung Jewish communities.

“Traveling as much as I usually do throughout the Jewish world and the lost tribe communities, I’ve enjoyed a life filled with every color of Am Yisrael,” says the rabbi. “It’s difficult for me to be apart from them for so long.”

But at least he’s surrounded by so many of the objects that remind him of those far-away communities. “Looking at them, we can learn so much about our people’s history over the centuries and in the different cultures where we’ve found ourselves,” he says. “They can wake up Jewish souls one piece at a time.”