oe Berlinger says he was troubled when he read reports of a 2018 study from the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany, which showed one in 10 millennial Americans thought that Jews were responsible for the Holocaust, and half could not name a single concentration camp.

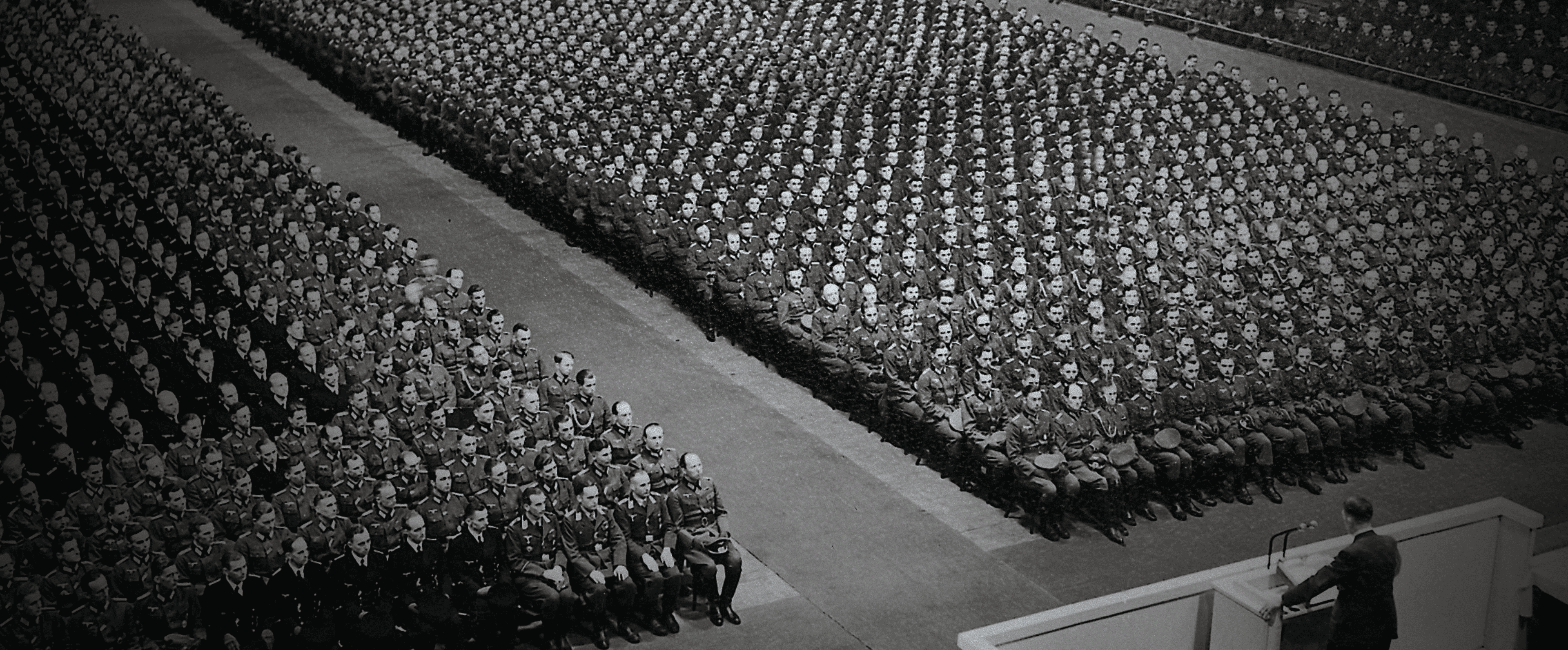

So Berlinger, a two-time Emmy Award winner and Oscar-nominated film director who has covered serial killers like Ted Bundy, Jeffrey Dahmer and John Wayne Gacy, in addition to world events such as the Armenian genocide (“Intent to Destroy” in 2015), decided to make “Hitler and the Nazis: Evil on Trial” released on June 5 on Netflix. The docuseries, which is in English, examines Adolf Hitler and the rise to power of the Nazi Party, from pre-World War II to the Holocaust to the Nuremberg trials.

Berlinger explains that he wanted to show parts of the trials and create a foundation using the work of William L. Shirer, the American journalist and war correspondent who covered the ascent of Nazism in Germany and wrote some of the seminal books on the topic, including The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich.

He adds that he was partly motivated by the erosion of truth and the spread of hate on social media. “I think we’ve moved from Holocaust denial to Holocaust affirmation,” Berlinger told JNS. “The phrase ‘Hitler was right’ was posted 70,000 times on social media last year.”

The first season consists of six episodes, titled “Origin of Evil,” “The Third Reich Rises,” “Hitler in Power,” “The Road to Ruin,” “Crimes Against Humanity” and “The Reckoning.”

‘A present-tense quality’

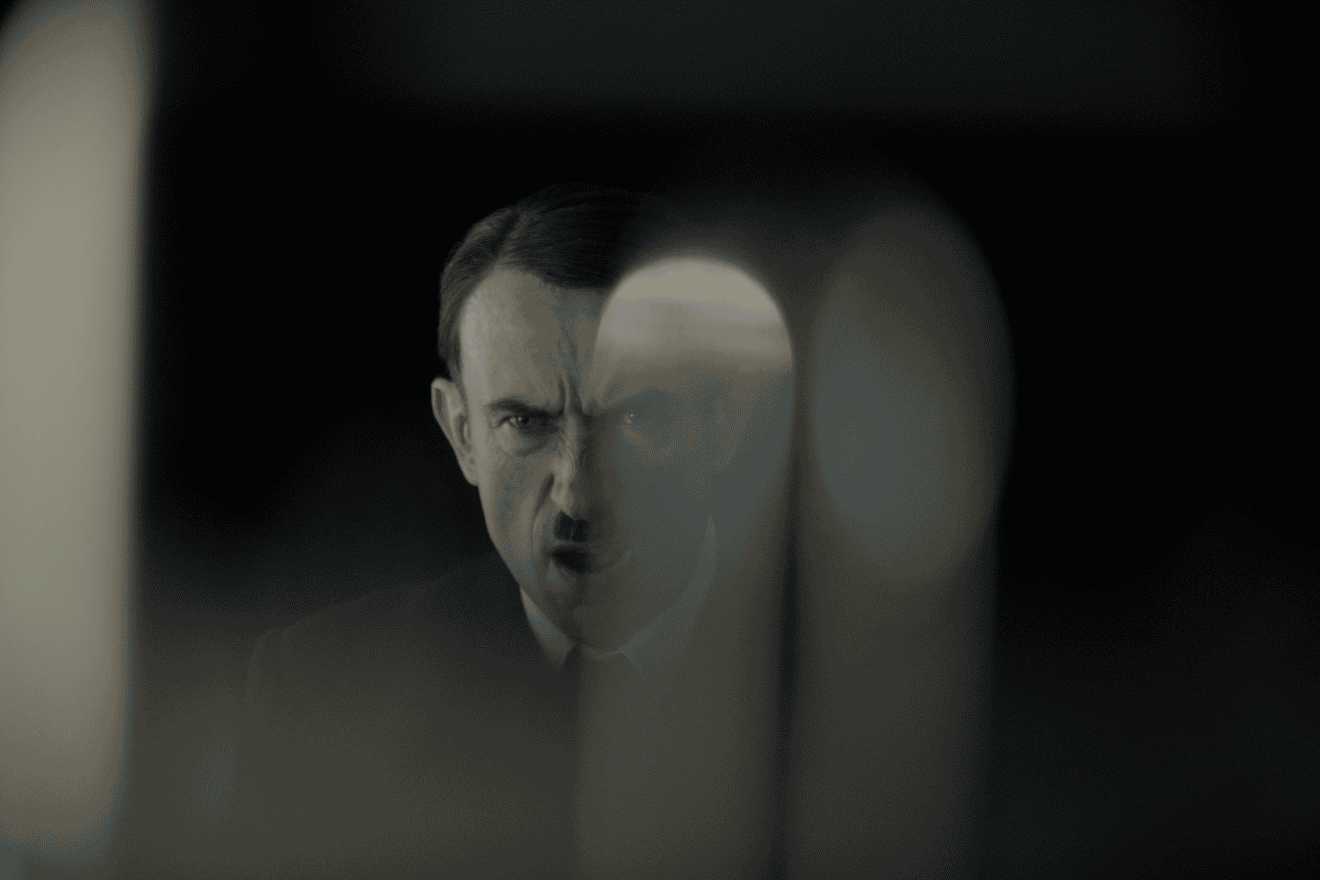

What’s different about the series are certain visuals. Berlinger, 62, says he lit some interviews with people on a stage and used other techniques in an attempt to appeal to a younger audience.

“I’m not being critical of how others make shows, but generally, there are talking heads intercut with crusty, grainy old footage and lack contextualization,” he says. “For older audiences who went through this, that approach is fine, but for a younger audience, I wanted to kind of use the language of cinema and bring Shirer to life as an eyewitness to events.”

He points out that colorizing archival footage and using artificial intelligence to have Shirer, who died in 1993, as a narrator were key aspects of these techniques. Another was to have dramatic re-creations, such as Hitler’s final moments in his bunker, with an actress playing Eva Braun holding a cyanide pill and an actor playing Hitler holding a gun to his head.

“I wanted to give it a present-tense quality,” says Berlinger.

He adds that AI “is a real hot-button issue in our business” with many objecting to it in any form, though he thought in this case, it was fitting.

“We were using [Shirer’s] radio broadcasts with a distinctive Midwestern accent, and this technology is available,” he says. “I thought bringing his voice to life with permission from his family made sense.”

‘There is no longer a standard of truth’

Some have used AI to have Hitler speaking in English, but that would be inappropriate in a documentary, he states.

Still, viewers hear Shirer’s words that Hitler was flabby, ordinary and unimpressive. He later regrets that he got it wrong and that he didn’t fully understand Hitler’s power or ability to bring about the expanse of the Holocaust. Is Shirer too hard on himself?

“Yes and no,” Berlinger says. “It’s easy in hindsight to say what should have been done or uncovered. I don’t take it to be him beating himself up. I just think the death camps were a shocking revelation. Anyone in a reporting function would naturally feel guilty for not catching the story sooner.”

He continues, saying those “who should be flogging themselves, as [director] Ken Burns points out so beautifully in his PBS series ‘The U.S. and the Holocaust,’ are people in power who knew and didn’t do enough. We might think if more was known and there was a public outrage, it could have changed history. But that, too, may be wishful thinking because antisemitism and quota systems were rampant then.”

He says that’s why he included the history of the St. Louis, a ship with 900 German Jews that made it to the outskirts of the Florida coast in June 1939 and was turned away by U.S. officials. It returned to Germany, where nearly a third of its passengers were eventually murdered.

The documentary shows a foolish miscalculation by German Chancellor Franz Von Papen, who recommended Hitler to be named the next chancellor, thinking that he could control him, and also depicts the failed assassination attempt by Claus von Stauffenberg, who left a bomb in a briefcase under a table near Hitler, only to have it unwittingly moved by another officer.

Berlinger says one thought is often in his mind. The greatest ‘what if’ is what if he had been accepted to art school?” Berlinger asks. “I think the world would be a very different place. It shows the ripples of history.”

Berlinger says he’s not surprised that some are denying the atrocities that took place on Oct. 7 by Hamas and Palestinian operatives in southern Israel because of an environment of misinformation on social media.

“There is no longer a standard of truth,” Berlinger says. “You can’t put the genie back in the bottle with how social media has eroded it.”

‘I couldn’t get it out of my head’

As a secular Jew from Westchester County, N.Y., with his father’s side from Germany and his mother’s side from Poland (his ancestors came to America in the 1850s), Berlinger was struck when at 15 he saw archival footage of Buchenwald, one of the largest concentration camps established within the German borders.

“It blew my mind, and I couldn’t get it out of my head,” says Berlinger.

“I couldn’t stop thinking about it as a young man,” he continues. “Had I been born back then, I clearly would have been murdered, and I couldn’t believe that people could do that to each other.”

He notes that he became a German major at Colgate University and embraced the positive aspects of German culture. He was fluent upon graduation, worked in the Frankfurt office for a New York advertising agency, and it was then that he realized he wanted to be a filmmaker.

He notes that “35 years later, coming back and telling this history with Netflix with a budget to do it in the way that I did was a fulfilling moment for me.”

And yet, he adds, he is fearful of what may lie ahead.

“The way the world is lining up, I do think we are on the precipice of World War III,” Berlinger says. “I hope it doesn’t happen, but we are dangerously close.”