Arabs rioted on the Temple Mount throughout the Islamic holy month of Ramadan, which ended early last week. Although Palestinians initiated the violence (evidence shows they had gathered rocks and fireworks ahead of time), they presented the rioting as a defensive action, claiming it was in response to Israeli changes to the Temple Mount’s status quo.

In reality, the situation on the Temple Mount is far from static, having been challenged by both sides. Jews have prayed at the site for years, albeit in a private, non-demonstrative way. Muslim alterations have been far more dramatic, including the construction of new mosques and the flouting of numerous smaller rules.

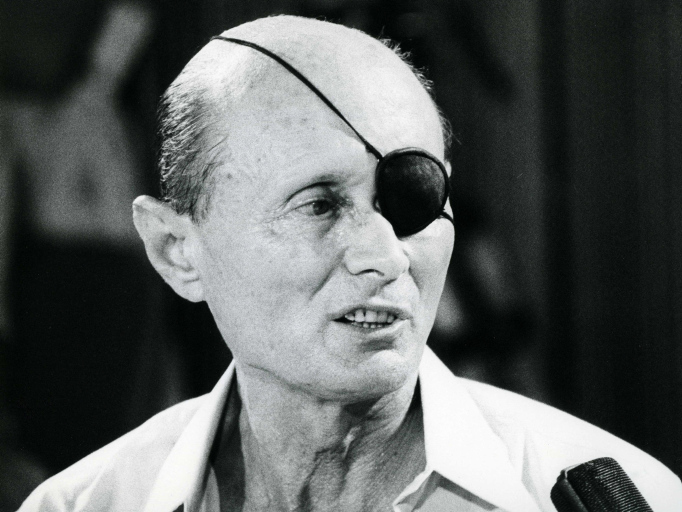

With regard to the mount, “status quo” refers to an agreement reached immediately after the Six-Day War in June 1967, when Israel reconquered the Old City of Jerusalem. According to that agreement, formulated by then-Israel Defense Forces Chief of Staff Moshe Dayan, the Muslim Waqf, a Jordanian religious trust, would retain control of the Temple Mount, though with a few changes. Jews would be allowed to visit the site without restrictions, though they would not be allowed to pray there. Israel would also take responsibility for security, though its forces would stay off the mount.

According to an April 2014 report by the Knesset Research and Information Center, citing research by Israeli historian Amnon Ramon, Dayan was attempting “to neutralize, as far as possible, the religious aspect of the Israeli-Arab conflict. He believed that leaving the management of the Temple Mount in the hands of the Muslim authorities would prevent an uprising in the territories of Judea and Samaria and in the other Muslim countries and would facilitate adaptation to Israeli control.”

The fear of a local, even regional Muslim conflagration sparked by religious anger over perceived Jewish misdeeds on the Temple Mount, currently known to Muslims as Al-Aqsa, remains the main concern among Israeli Jews who oppose Jewish prayer on the mount. A recent poll found that of 40% who opposed Jewish worship there, the majority (23%) did so out of fear of a backlash in the Muslim world.

He said that relations between Israel and Muslim states have improved, but that the Temple Mount is such a sensitive issue it could reverse those advances, pointing to recent demonstrations in Jordan, Bangladesh and Indonesia.

“Nobody in Israel wants all that we’ve built during the last 25 years—I’m talking about the peace with Jordan, the peace with Egypt, the special relationships that we have with Saudi Arabia, with Oman—nobody wants everything to be destroyed because of the Temple Mount,” he said.

Israel denies any changes have been made to the status quo. Israeli Foreign Minister Yair Lapid called a press conference in Jerusalem on April 24 in part to stress that point.

However, few deny that Jews have been unofficially praying on the mount. Yisrael Medad, a Temple Mount activist for over 50 years, makes no bones about it. He made his first trip to the site in October 1970, shortly after immigrating to Israel, and describes a “cat and mouse game” with police as his group tried to hold prayers at the site. The police came up with a restriction (largely effective) for some 15 years that allowed only seven Jews up at a time, thus preventing the minimum number of 10 Jewish men required for a prayer quorum.

Medad believes that Israel should not allow threats of Muslim violence to dictate what Jews can or cannot do on the Temple Mount. “Once you accept the position that your enemy, or your rival, sets the rules, and you have no say in what those rules are, whatever you do will be wrong in his eyes,” he told JNS.

Visiting the Temple Mount, the holiest site in Judaism and the location of Solomon’s Temple, was “way out there” in the 1970s, Medad admitted. “If there were more than 100 people going up in a year, it was something amazing,” he said.

Today, thousands of Jews visit the site annually. Medad dates the change to 2003, after the Temple Mount had been closed to Jews for three years following Israeli opposition leader Ariel Sharon’s visit in September 2000. That visit was blamed, it later turned out falsely, for sparking the Second Intifada. “After three years in which the Temple Mount was completely shut off to Jews, people began to realize we could lose it. And this was the turning point,” Medad said. Rabbis started to issue religious edicts permitting visits to certain parts of the Temple Mount.

Until then, the religious consensus was that Jews should not visit the Temple Mount, as doing so would desecrate holy ground. “No one wanted to break with the tradition of 300 to 500 years,” said Medad. He noted an instance where Moses Montefiore, a wealthy British-Jewish financier, was carried onto the Temple Mount in a litter in the mid-19th century and nearly excommunicated for it by Jerusalem rabbis.

Non-religious Jews also began to change their minds about the site. The reason was the construction of the El-Marwani mosque, a large Muslim prayer hall on the Temple Mount. In the late 1990s, Muslim authorities dumped hundreds of tons of dirt containing archaeological finds. “That horrified secular people. Archaeologists said, ‘We’re not for prayer. We don’t want to bother the Arabs. But you can’t walk into the Solomon’s Stables and dump out tons and tons of material,’ ” said Medad.

Medad argues that there are a host of reasons as to why Jewish prayer should be allowed, including upholding Israeli sovereignty, freedom of worship and basic fairness. “If you accept that Muslims have an equal claim to the Temple Mount (though I would say we have a primary claim), where’s the tolerance? Where’s the compromise?” he said.

The origins of Dayan’s status quo can be traced back to the 13th century, he said. After the Muslims drove out the Crusaders and retook the Temple Mount, they declared that “no foreigner who is a non-Muslim” could enter the site. The first modern iteration of this medieval decision was not 1967, but 1928, said Medad, when the British, who then controlled Palestine, issued a white paper that said Jews have no right to any permanent structures at the Western Wall. The motivation then, too, was forestalling Muslim violence.

Since the 1967 agreement, there have been so many changes that a status quo can’t really said to have been established at all, Medad argued, referring to Article 9 of the Israel-Jordan peace treaty, which calls for freedom of worship at holy shrines in Jerusalem; Israel’s Protection of Holy Places Law, “which basically allows us to pray on the Temple Mount”; and Israeli Supreme Court rulings, which have allowed Jewish prayer at the site.

Medad also noted that the ostensible status quo is supposed to refer to both sides, and Muslims have made many modifications to the site, among them the aforementioned El-Marwani mosque.

“It’s as if the status quo is only for Jews. If it’s a status quo, then shouldn’t both sides be static?” he said.

Hebrew University researcher Shaked agreed that Israel has done a poor job of imposing its sovereignty on the Temple Mount, noting as a recent example the arrest and almost immediate release of 300 rioters, most of whom, he said, were members of Hamas. In fact, Shaked said, if anyone controls the Temple Mount, it’s Hamas.

“We gave fanatical groups, and especially Hamas, the run of the place,” he said. “If a regular Muslim just wants to come to pray there, that’s one thing. But those who want to use the Temple Mount as a place for incitement, as a base of fighting against Israel, those we must fight. Up till now, we have shown a weak hand.”