Not only does Yiddish date back many centuries, but an exhibit in New York contains a 16th-century Yiddish example of a Jewish mother trying to guilt trip her son into communicating with her more regularly.

The Jerusalem-based Rochel Zussman wrote in Yiddish in the 1560s to her son Moishe telling him that more professional opportunities await him in the Holy Land than in Cairo, where he lived.

“It’s the sort of yearning of a mother for her son to come back to her,” Eddy Portnoy, academic adviser and director of exhibitions at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, told JNS. “One of the interesting things is she does mention that he doesn’t write to her enough.”

“The kind of classic Jewish mother trope exists in Yiddish in the 1560s, in Jerusalem and Cairo, which is kind of amazing,” Portnoy added. “That was the first evidence I found of Yiddish in Ottoman-ruled Palestine.”

Portnoy is the curator of YIVO’s exhibition “Palestinian Yiddish: A Look at Yiddish in the Land of Israel before 1948,” which opened on Sept. 5.

Muscled out

When Portnoy began researching the exhibit a year ago, he didn’t realize how much depth there was to the existence of Yiddish in the Holy Land prior to the advent of Zionism.

When Hebrew was revived in the modern-day Israeli state, it largely muscled out the region’s Yiddish, which borrowed heavily from the Ottoman Empire’s dominant Arabic.

Portnoy discovered a small packet of letters from the Cairo geniza, now housed at Cambridge University. The letters were among some 400,000 items that spanned from the 6th to 19th centuries, which were housed in the geniza—a storehouse for Jewish items that are too sacred to destroy—at Cairo’s Ben Ezra Synagogue.

The discovery marked the beginning of Portnoy’s project to trace the rich and largely unknown history of Yiddish in the area that was largely lost to Israel’s rebirth.

Centuries-old modernization

Yael Chaver, a Yiddish lecturer emerita at the University of California, Berkeley and author of the 2004 book What Must Be Forgotten: The Survival of Yiddish in Zionist Palestine, consulted with Portnoy on parts of the show.

“It’s sort of paradoxical to speak of modernizing by going back to a 4,000-year-old language,” Chaver told JNS. “But Hebrew became modernized around the turn of the 20th century and became identified with political Zionism. The Yiddish writers dealt with topics and with themes that the Hebrew writers did not often get to.”

Yiddish has enjoyed good public relations in popular culture today, but its usage in pre-state Israel “has been underrepresented,” according to Chaver.

“The idea of the Zionist was to change: change place, change culture, create a new culture in a different land, and since Yiddish was the hallmark of the old way of existence, Zionists viewed that as negative,” she told JNS. “There was this tendency to go back to roots, and, of course, Hebrew is the language of the Bible.”

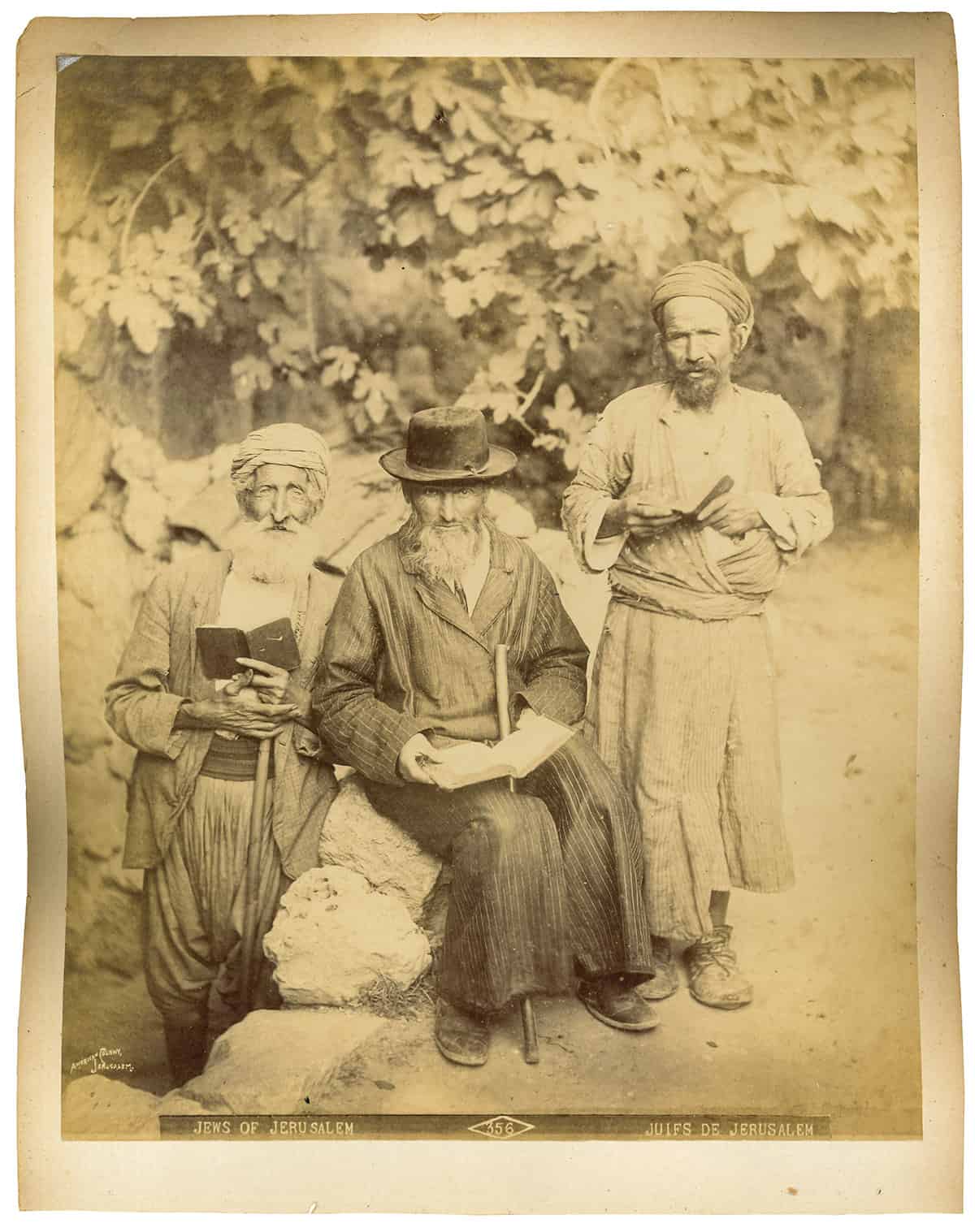

Ashkenazi communities in pre-state Israel were quite small, but those populations began to grow in Jerusalem, Tzfat and Tiberias in the late 18th century, when Chassidim began to immigrate. Smaller groups of Ashkenazi Litvaks (non-Chassidim) followed.

“In spite of living in a place where they’re a tiny minority, Ashkenazim maintained Yiddish as their vernacular,” Portnoy said. “Because they lived in a place where Arabic was the dominant language, their Yiddish contains a lot of Arabic.”

Lapsing into Yiddish

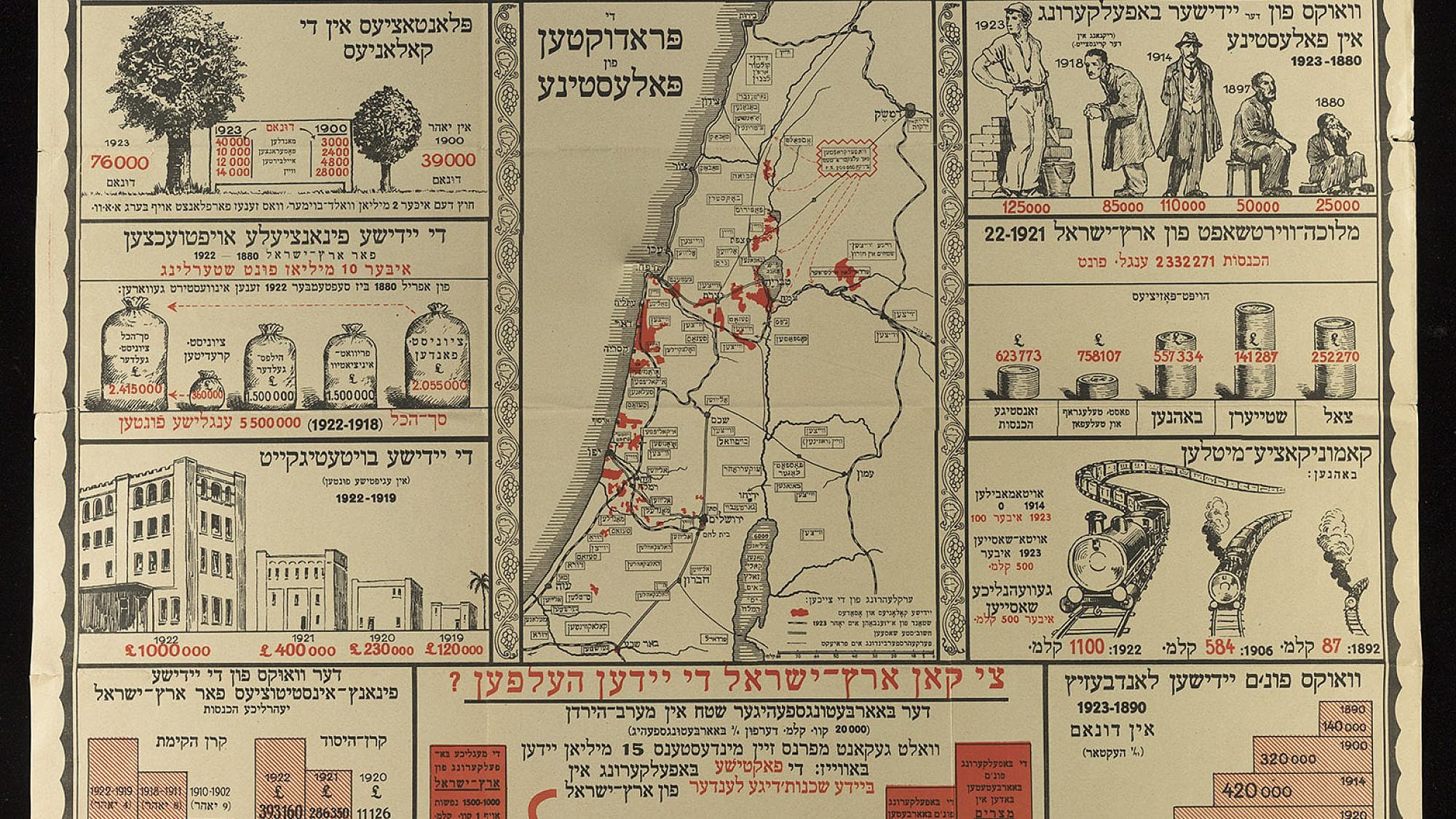

The YIVO exhibit, which fills one room, contains about 20 publications and 15 reproductions and photographs. One section includes the book Palestinian Yiddish by Mordechai Kosover, a Jewish immigrant from Poland, who arrived in the Holy Land in the early 1920s and lived through Ottoman and British rule.

A student with interests in Yiddish language and culture, Kosover was also an activist who studied the language of the Old Yishuv, the region’s earlier Yiddish-speaking communities. He interviewed Ashkenazim in Jerusalem’s Old City and documented hundreds of examples of the ways that Arabic words and phrases entered the Old Yishuv’s Yiddish lexicon.

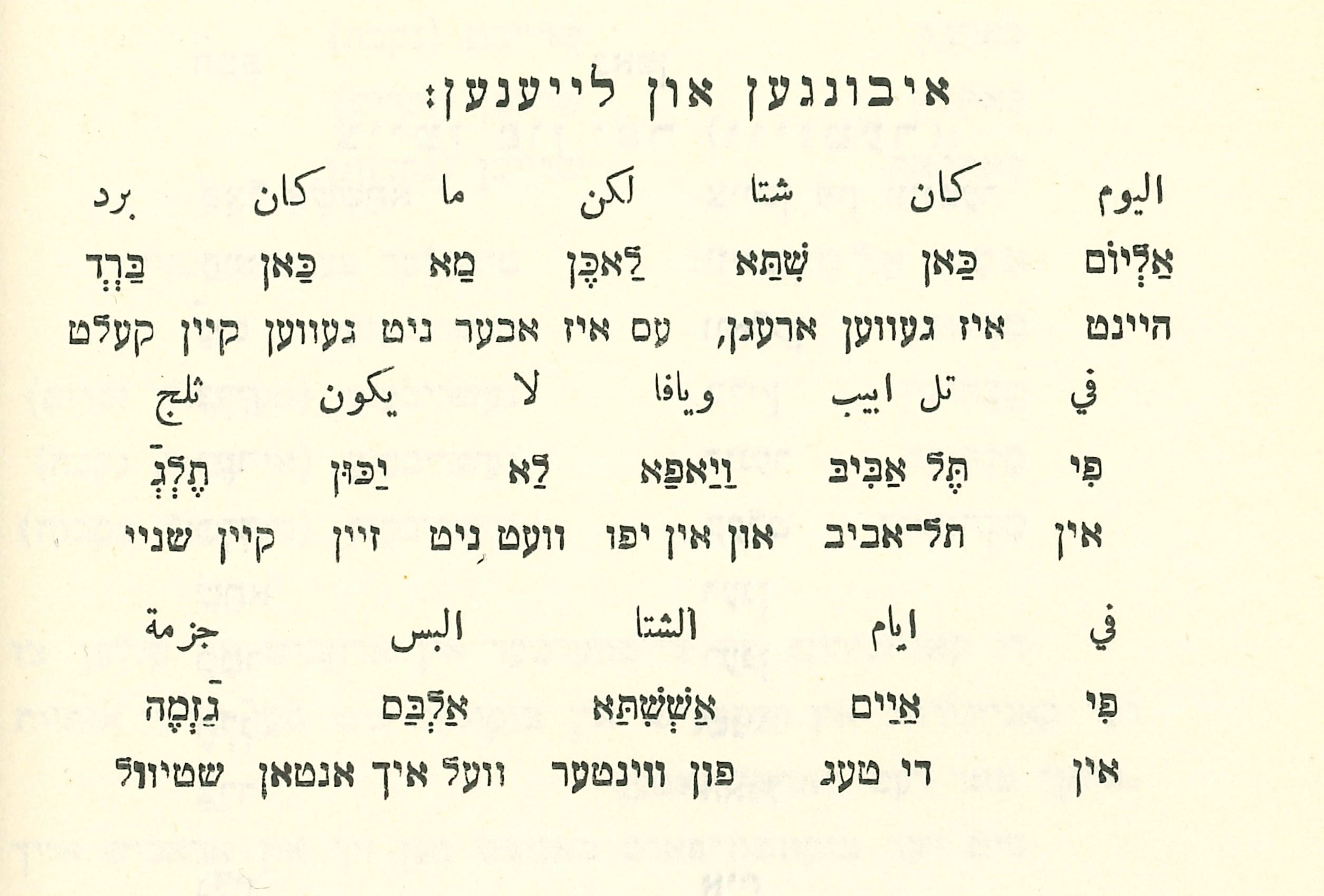

The exhibit features three textbooks that teach Arabic by transliterating it into Yiddish.

Throughout, the exhibit describes the views of many early Zionists, who sought to transition away from Yiddish, which they saw as connected to a beaten-down exile.

Some early defenders of Hebrew over Yiddish, including the powerful political group Hapoel Hatzair, went to great measures to reduce the use of Yiddish, including reporting its use in local meetings to authorities; shouting down residents attempting to speak or sing in Yiddish; and establishing an informal rule prohibiting use of foreign languages in public forums for those who had lived in the country for more than two years.

“These groups feared that it would be too easy to lapse into Yiddish because the vast majority of Jewish immigrants to Palestine were Yiddish speakers,” Portnoy said. “In the newspapers, you can find complaints that people would write, detailing a meeting where everyone was speaking Yiddish, even the children.”

“This was very troubling to the people who were trying to promote Hebrew,” he added.

Those trying to rid the Holy Land of Yiddish refused to name the latter, instead referring to it as jargon or with the Hebrew expression for “the spoken language.”

“There’s an interesting parallel between anti-Zionists who refuse to say ‘Israel,’” Portnoy said. “They say ‘the Zionist entity.’ They refuse to call it what it is.”

Farbrente fisticuffs

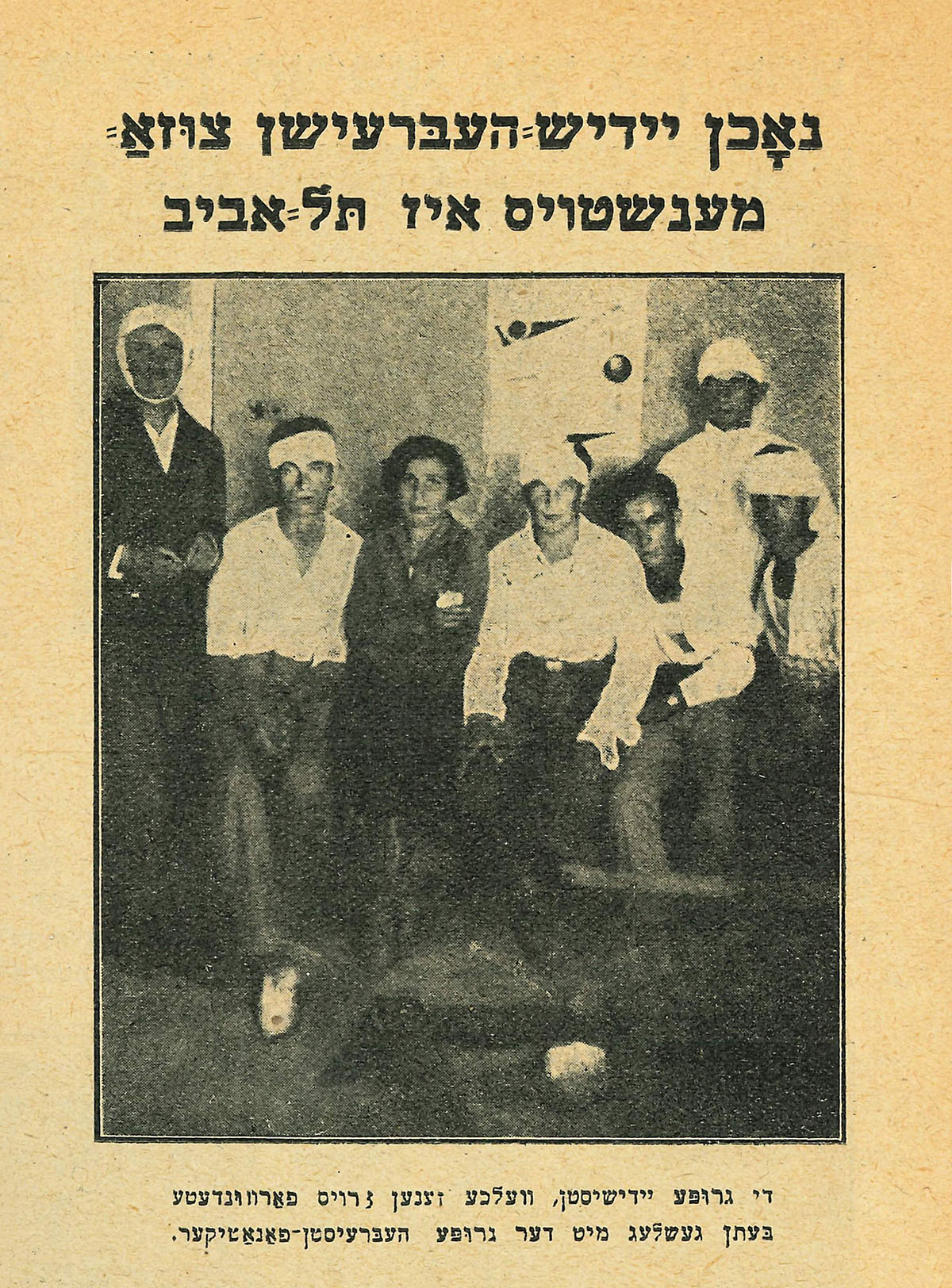

A photograph in the exhibit shows Yiddishists whom Hebraists attacked during a 1928 meeting. The image is “very reminiscent of photographs of Jews who suffered pogroms,” according to Portnoy.

“They’re shown bandaged up, and it’s obvious something horrible has happened to them,” he said. “The same sort of thing happened here—all in connection to Yiddish, which seems kind of crazy. But people were fanatics. They were involved in a revolution in Jewish life.”

Yiddish has survived in some Israeli religious neighborhoods, but outside of those, it tends to be largely a nostalgic thing in Israel today, with expressions or jokes posted on social media.

“Now that it is no longer a threat, I think it’s easy for people to enjoy it,” Portnoy said. “I think that certainly people miss it as well because the language that you grew up in is the carrier of your culture.”