The Catholic Monarchs, King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile took control of the Emirate of Grenada (1238-1492), the last Moorish stronghold in Spain, on January 2, 1492. King Boabdil surrendered to Spanish forces and offered the key to the city in the Alhambra palace, an event Christopher Columbus witnessed as he received the support of the monarchy to sail to the Indies.1

The monarchy was under particular pressure from Isabella’s father, Tomas de Torquenada, and also papal appeals and influential militant figures to re-conquer Christian land from “impure” Muslims and their “filthy” allies, the Jews.2 In the same year that the monarchs took Grenada, Constantinople fell to the Ottomans in Christian Byzantium, further threatening Christendom and reinvigorating Europe’s crusading spirit.

The Expulsion Of Muslims And Jews

The monarchy, thus, extended their Inquisition throughout southern Spain and quickly targeted the Sephardic Jews, also called the Megorashim. They were forced to either convert to Christianity or leave Spain within four months without any possessions 3. Failure to leave resulted in torture and / or death. Even those claiming conversion, the Moranos, were subjected to severe persecution and higher taxes, wore distinguishing clothing with yellow badges, and were, all around, regarded with deep suspicion 4. The options for exile – Eastern Europe, Europe, or North Africa – all carried considerable risks and tribulations. It was, however, the North African Jews who enjoyed greater reception, freedom and treatment 5, 6.

On the topic of the presence of the Jews in Spain, Norman Roth writes 7:

“The possible end of the Jewish presence in the Iberian Peninsula was prevented by the Muslim invasion of North African Berber tribes in 711. The Jews, used by the small invading Muslim forces to garrison conquered cities, soon became integrated into Muslim Society. Increased immigration of both Muslims and Jews from Islamic lands rapidly built Spain into a major political and cultural center, from Andalusia in the South to Barcelona in the north. Muslims established an independent caliphate in Cordoba, where Jews played a key role in the cultural renaissance that followed. From government service to the market place, Jews and Muslims interacted with little or no tension.”

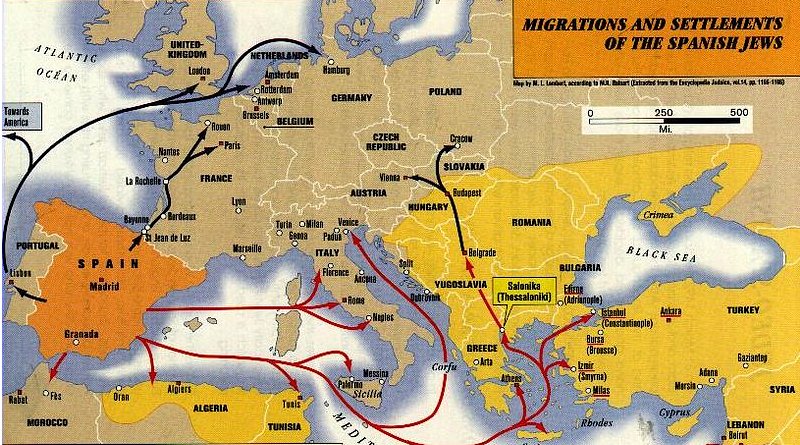

The Edict of Alhambra was signed in March 1492 and after the Jews were expelled on July 31, 1492 they settled in Morocco, other North African countries, Europe, and the Ottoman Empire. Although their long history had come to an end in Andalusia, the Megorashim in Morocco found cultural cohesion with their new community and settled into privileged positions in the political and economic sectors.

In 1496, under political pressure from the Spanish monarchs, King Manuel of Portugal issued a similar decree, effectively emptying the entirety of the Iberian Peninsula of its Jewish inhabitants. The Spanish and Portuguese Edicts of Expulsion prompted a massive exodus of Jews across the Mediterranean and north European basins.

Sizable communities relocated to Amsterdam, Poland, and Ottoman lands in the East such as Sarejevo, Istanbul, and Salonika. However, a large fraction of these refugees, estimated by scholars to be around 50,000, fled to Morocco. The Wattasid ruler of the time, Sultan Sheikh Mohamad al-Wattasi, welcomed the incoming Jews with open arms, aided their resettlement in prominent urban centers such as Fez 8, Tangier, and Sale, and placed notables in important political and commercial positions.

Though relations between the kingdom’s original Jewish inhabitants, the Toshavim, and the post-1492 refugees, the Megorashim, were initially tense, the newcomers assimilated into Moroccan society with astounding success. Their contribution to both Jewish and Muslim life, from politics to poetry to commerce, was enormous.

Adaptability Of Jews

As Ibn Khaldoun argued, Jews had a long history of adapting to, persevering and thriving in new environments. Jews immigrated to Spain (Country of Tarhish) to conduct trade as early as 200 BCE, as recorded in the books of Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Jonah and Romans. Jews from Judea, expelled under Titus in 139 BCE, brought them to Tarhish as citizens of the Roman Empire.

As early as 65 CE, anti-Semitism began to crop up in response to Jewish community’s success in commerce within Spain and with other kingdoms. Tolerance of the Jews fluctuated for centuries from Justinian Edicts in 527-565 to the Visigoths maltreatment and attempt to force conversion or exile in 699 to the Moorish conquest of al-Andalus in the 8th century.

As a reflection of Ibn Khaldoun’s salient sociological concepts, Hillel Frisch argues in The Jerusalem Post 9:

“Ibn Khaldun’s ideas, whether consciously or unconsciously, were hardly foreign to the philosophy of Zionism. From A.D. Gordon to the spiritual essays of HaRav Kook, from HaShomer to the Palmah, there was an awareness that the Jews in the Diaspora, praised for the tenaciousness of keeping the faith, were losing their spiritual compass and to a certain sense their asabiyya. The call for pioneers to work the land in the periphery, the Jew “who conquers the mountains” where the forefathers of the nation treaded, reflected the themes of Ibn Khaldun.”

A golden age of Judaism emerged under the Ummayads of Cordoba (756-1031); and the “adaptability of the Jew” proved forthright: Jews learned Arabic, climbed the socio-political ladder and held powerful positions in the palace as trusted advisors, controlled trade and maintained prestigious occupations 10.

Although dhimmis were not supposed to be above Muslims in theory, this was commonly the practice in Moorish Spain. The Kingdom of Grenada, for instance, had a Muslim Emir and a Jewish vizier named Samuel ha-Naguid (d. 1056) 11, who was succeeded by his son Joseph.

This was not without retribution and indeed sparked a pogrom resulting in the death of 5,000 Jews and destruction of their quarter. Conditions oscillated under the Taifa kings, and worsened under the puritan rule of the Almoravid (1040-1147) and Almohad (1121-1269) dynasties.

Jews fared better under the Almoravids despite dhimmi status and regulations than the Almohads, wherein thousands of Jews were killed between 1130 and 1232, convert or death threatened again in 1147, Mellahs were created and the yellow star on clothing enforced; this encouraged many prominent Jewish families and figures (i.e. Abraham Ibn Exa, Seti Fatma, Juda Habri, Maimonides) to flee Spain. Thus, the dynasties’ relationship with the Megorashim shifted from coexistence, uneasy toleration, to brutal persecution throughout the centuries. But the Jews by and large persevered until the Christian conquest in 1492.

The Sephardic Jews Greeted In Morocco

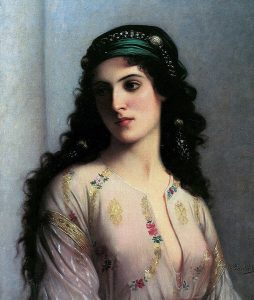

Upon their expulsion, the Sultan of Morocco, Muhammad Sheikh al Wattasi, was amenable to the new arrivals and recognized the Megorashim as valuable assets. They were ushered into positions of authority as administrators, palace advisers in foreign and military affairs, and leaders in trade and commerce. They also thrived as doctors and moneylenders, especially in Fez, Sefrou 12, Marrakech, and Essaouria.

Although the local Tovashim, rural and urban, had flourished in Morocco since the fall of the Temple in 70 AD, the Wattassid favored the new arrivals due to their education and sophistication. Animosity between the two Jewish communities grew, especially since the Megorashim spoke Hekitia (mixture of Spanish, Hebrew and Darija) and refused to speak Darija 13. They initially settled in Fez and the southern regions, while the Tovashim remained in the northern cities and rural areas. The two communities lived separately until the 18th century.

Jews, also, monopolized maritime trade and banking under Sa’di dynasty (1554-1655) and conducted business and diplomacy on the Sultan’s behalf. Moranos migrating to Morocco later on to Fez 14, Tetuan and Meknes developed the sugarcane industry and developed the tea trade with India and China propelling the Barbary state into prosperity.

Rural Jews developed the caravan trade (gold, ostrich, feathers and women) in Fez and Sefrou as they were the trusted guides (azettat in Tamazight (Amazigh/Berber language)) and expert negotiators. During Portuguese occupation of Safi and Azemmour, the Megorashim served as translators and negotiators, contributing to the roots of the would-be protégé system of the 19th century in Morocco 15.

The ‘Culture Of Expulsion’ Of The Megorashim

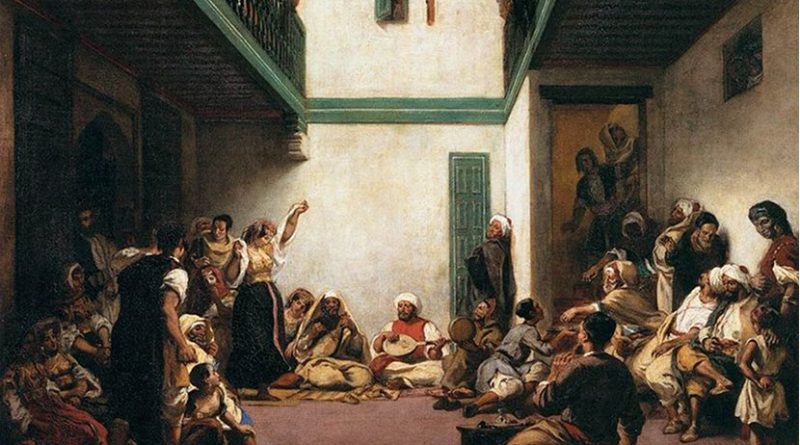

The Megorashim adapted to Morocco, but they also infused their culture into the local milieu. So much so that within a few centuries it was indistinguishable from Moroccan culture. This included the “culture of expulsion”, especially Andalusian music and poetry from Grenada and Cordoba. The music stressed Kebbala spirituality that found easy reception with Sufism. Cuisines also overlapped and were no longer distinct, including sardine and garlic recipes of Safi and Essaouria; Mahya fig liquor; and baqeeya (Paella), just to name a few. Clothing customs also merged, most noticeably the colorful kaftans with gold embroidery worn by Moroccan brides.

Another factor that contributed to the success of the Sephardic Jews on Moroccan soil was the rich culture they brought in tow from their former glory days in Spain.

During the Spanish-Islamic Golden Age, Jews contributed to important developments in a diverse number of fields. From Zoharic Kabbalah to Judah haLevi and Ibn Gabirol’s sublime poetry to Maimonides polymath genius to the distinctive Andalusian musical tradition and cuisine, the incoming Jews were an astonishingly refined group.

Upon arrival in Morocco, they quickly distinguished themselves as first-rate scholars, significantly revitalized native Jewish life, and bequeathed a rich heritage of music, dance, dress, and food, not to forget, also, social etiquette, to their Jewish and Muslim countrymen alike. The impact of this cross-cultural exchange was so profound that it is still observed today, five centuries later, in contemporary Moroccan music and food.

As such, the Spanish Jews ascended to the upper ranks of Moroccan cultural life, collaborating with both Toshavim and Muslim communities in the dissemination of their inherited knowledge and traditions. This secured them respect and admiration that transcended religious and ethnic barriers, enriching Moroccan culture as a whole in the process and strengthening the Moroccan sense of tolerance and religious wasatiyya 16.

Sephardic Jews And Contribution To Muslim Golden Age In Spain And Rise Of Moroccan Empire In Africa

From the days of the Ummayad Caliphate in Cordoba in the 8th century A.D., Jews had served Spanish Muslim rulers as high-ranking diplomats and personal advisors.

Through their relaxation of the limitations imposed by Dhimmi status on the participation of religious minorities in public life, the Ummayad Caliphs (e.g. Abdul Rahman III) were able to create a pluralistic palace culture that took advantage of their Christian, Muslim and Jewish subjects’ religious diversity. The political advice of individuals such as Samuel ha-Nagid and Hasdei Ibn Shaprut contributed to the prosperity and far-reaching cultural and intellectual achievements of the Spanish-Islamic Golden Age. Jews continued to play an important political role in Muslim Spain through the twilight of the Emirate of Granada.

The Jewish refugees that fled to Morocco in 1492 and 1496 carried this venerable history of political service with them and readily applied it to their new circumstances. The role they quickly assumed in the Wattasid court allowed them to forge critical ties with the Moroccan political elite and gain the trust of the Sultan. This move catalyzed their assimilation into Moroccan society, established amicable relations with the Muslim rulers, and placed them in an overall privileged societal position.

Lastly, the incoming Sephardic Jews were regarded as excellent merchants, leading to the subsequent accumulation of material success despite the total loss of their assets that the expulsion from Spain entailed. The dispersal of the Spanish Jewish population across the Mediterranean world and beyond afforded them far-reaching commercial contacts not enjoyed by their competitors. Their prominent positions that straddled the commercial nodes of the Ottoman Empire (e.g. Istanbul, Antioch, and Salonika) and European maritime states (e.g. Venice and Amsterdam) allowed them to sink stakes in the lucrative spice and luxuries trade. Able to procure cheap goods in the East, Jewish merchants sold spices, gems, etc. for astronomical prices in major European cities.

Through familial and commercial relations, the Moroccan Megorashim were able to participate in this vast trade network by playing an important role in linking Mediterranean and Atlantic shipping routes. These connections brought great material wealth to the upper ranks of the Moroccan-Sephardic Jewish community, endowing them with greater political and social leverage and contributing to their general success in assimilating into Moroccan society.

Last Word

Overall, the Megorashim of Morocco were able to transfer the skills they had cultivated throughout their long and tumultuous history in Spain to adapt and thrive in their new environment. Their golden days in Morocco, like that of Al-Andalus, reached great heights; but the Jewish community as, a whole, experienced fluctuations in tolerance and, indeed, persecution that would reach its intolerable zenith in the mid-20th century 18. Although the community has dwindled to negligible numbers, the Megorashim nonetheless left an indelible mark upon Moroccan culture still present today which is proudly reflected in the Preamble of the Moroccan Constitution of 2O11 19:

“A sovereign Muslim State, attached to its national unity and to its territorial integrity, the Kingdom of Morocco intends to preserve, in its plentitude and its diversity, its one and indivisible national identity. Its unity, is forged by the convergence of its Arab-Islamist, Berber [amazighe] and Saharan-Hassanic [saharo-hassanie] components, nourished and enriched by its African, Andalusian, Hebraic (emphasis mine) and Mediterranean influences [affluents]. The preeminence accorded to the Muslim religion in the national reference is consistent with [va de pair] the attachment of the Moroccan people to the values of openness, of moderation, of tolerance and of dialog for mutual understanding between all the cultures and the civilizations of the world.”

You can follow Professor Mohamed CHTATOU on Twitter: @Ayurinu

Endnotes:

- http://www.historiamag.com/fall-of-granada/ On the Fall of Grenada, Jane Johnson writes:“Everyone thinks they know the story of the Fall of Granada: how, after handing the keys over to Isabella and Ferdinand, the young sultan turned for one last time to look upon the city he loved; how his mother derided him for ‘weeping like a woman for what you could not hold like a man’; how that spot is called ‘The Moor’s Last Sigh’. But when I started in on some serious research I soon discovered that this was largely made up by Antonio de Guevara, Bishop of Guadix, for the benefit of Emperor Charles V when he visited Granada on his honeymoon in 1526, and that history – from both the Christian and Muslim perspectives – had treated that young sultan, Abu Abdullah Mohammed, known as Boabdil, cruelly. So I wanted to tell his personal story, as well as the great sweep of events leading up to the fall, which the poet Federico Garcia Lorca described as ‘a calamity, leading to a new dark age’.”

- https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Fall_of_Granada The fall of Granada marked the final act in the Reconquista, the campaign by the medieval Christian states of Spain to drive out the Moors. It was followed by the expulsion of Jews and Muslims from Spain, although some remained by converting to Christianity. Among these some remained secretly Muslim or Jewish (known as moriscos and morranos). Many, however genuine their conversion, were subject to the suspicions and interrogations of the Spanish Inquisition. In 1609, descendants of converts were also expelled. A society that had often seen Muslims, Jews, and Christians interacting positively had ended. The Fall of Granada was a factor in the Spanish and Portuguese drive to acquire overseas colonies, influencing their attitude of ineffable superiority towards the cultures and religions they encountered in the New World, for which Christopher Columbus set sail later in the year of Granada’s defeat. Rediscovery of the richness and positive cultural exchange of Moorish Spain before 1492, known in Spanish as convivencia, may provide clues on how contemporary multi-cultural societies can deal with the challenges of pluralism and of peaceful co-existence.

- Cf. Ashtor, E. 1993. The Jews of Muslim Spain. Jewish Publications Society.

- Cf. Murphy, Cullen (2012). God’s Jury: The Inquisition and the Making of the Modern World. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 75. Established by the Catholic Church in 1231, the Inquisition continued in one form or another for almost seven hundred years. Though associated with the persecution of heretics, Muslims and Jews – and with burning at the stake – its targets were more numerous and its techniques more ambitious. The Inquisition pioneered surveillance, censorship, and “scientific” interrogation. As time went on, its methods and mindset spread far beyond the Church to become tools of secular persecution. Traveling from freshly opened Vatican archives to the detention camps of Guantanamo to the filing cabinets of the Third Reich, the acclaimed writer Cullen Murphy traces the Inquisition and its legacy, showing that not only did its offices survive into the twentieth century, but in the modern world its spirit is more influential than ever. With the combination of vivid immediacy and learned analysis that characterized his acclaimed Are We Rome? Murphy puts a human face on a familiar but little-known piece of our past and argues that only by understanding the Inquisition can we hope to explain the making of the present.

- https://www.africanexponent.com/bpost/4516-ancient-relationship-between-sephardic-jews-and-catholics

- https://www.africanexponent.com/bpost/4517-the-history-of-sephardic-jews

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/24448257?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

- Cf. Gerber, J.S. 1980. Jewish society in Fez, 1450-1700 : Studies in Communal and Economic Life. Leiden : Brill.

- https://www.jpost.com/Opinion/Ibn-Khaldun-and-the-Law-Israel-The-Nation-State-of-the-Jewish-Nation-564440

- Norman Roth, “The Jews and the Muslim Conquest of Spain,” Jewish Social Studies 37 (1976). See also idem,”Some Aspects of Jewish-Muslim Relations in Spain,” in Estudios en homenaje a don Claudio Sanchez Albornoz (Buenos Aires, 1983), 2:179-214; idem “The Jews in Spain at the Time of Maimonides,” in Moses Maimonides and his Time, ed., Eric L; Ormsby (Washington , D.C.,1989), 1-20.

- https://www.britannica.com/biography/Samuel-ha-Nagid Samuel ha-Nagid, Arabic Ismail Ibn Nagrelʿa, (born 993, Córdoba, Spain—died 1055/56, Granada), Talmudic scholar, grammarian, philologist, poet, warrior, and statesman who for two decades was the power behind the throne of the caliphate of Granada. As a youth Samuel received a thorough education in all branches of Jewish and Islāmic knowledge and mastered Arabic calligraphy, a rare achievement among Jews. When Córdoba was sacked in 1013 by the Berbers, a north African people believing in Islām, Samuel fled to Málaga, at that time part of the Muslim kingdom of Granada. Samuel’s unusual linguistic and calligraphic skills caught the attention of the Granadan vizier, who employed him as his private secretary. He soon became an invaluable political adviser to the vizier, who, at his death, commended Samuel to the caliph Ḥabbūs. The caliph made Samuel the new vizier, and as such he assumed direction of Granada’s diplomatic and military affairs. Ḥabbūs died in 1037. Although his elder, pleasure-loving son then assumed the throne, Samuel was the caliph in fact if not in actuality. He steered Granada through years of continuous warfare and actively participated in all major campaigns. His influence became so great that he was even able to arrange for his son Joseph to succeed him as vizier.

- Cf. Geertz, C., Geertz, H., and Rosen, L., 1979. Meaning and order in Moroccan society: three essays in cultural analysis. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press

- http://www.sephardifolklit.org/flsj/OLSJ The Varieties of Judeo-Spanish, Until recently, two different dialects of Judeo-Spanish were spoken in the Mediterranean region: Eastern Judeo-Spanish (in various distinctive regional variations) and Western or North African Judeo-Spanish (also known as Ḥakitía), once spoken, with little regional distinction, in six towns in Northern Morocco and, because of later emigration, also in Ceuta and Melilla (Spanish enclaves in Morocco), Gibraltar (Great Britain), Casablanca (Morocco), and Oran (Algeria). The Eastern dialect is typified by its greater conservatism, its retention of numerous Old Spanish features in phonology, morphology, and lexicon, and its numerous borrowings from Turkish and, to a lesser extent, also from Greek and South Slavic. Both dialects have (or had) numerous borrowings from Hebrew, especially in reference to religious matters, but the number of Hebraisms in everyday speech or writing is in no way comparable to that found in Yiddish. The North African dialect was, until the early 20th century, also highly conservative; its abundant Colloquial Arabic loan words retained most of the Arabic phonemes as functional components of a new, enriched Hispano-Semitic phonological system. During the Spanish colonial occupation of Northern Morocco (1912-1956), Ḥakitía was subjected to pervasive, massive influence from Modern Standard Spanish and most Moroccan Jews now speak a colloquial, Andalusian form of Spanish, with only an occasional use of the old language as a sign of in-group solidarity, somewhat as American Jews may now use an occasional Yiddishism in colloquial speech (Hassán 1969). Except for certain younger individuals, who continue to practice Ḥakitía as a matter of cultural pride, this splendid dialect—the most Arabized of the Romance languages—has essentially ceased to exist. Eastern Judeo-Spanish has fared somewhat better, especially in Israel, where newspapers, radio broadcasts, and elementary school and university programs strive to keep the language alive. But the old regional variations (Bosnia, Macedonia, Bulgaria, Rumania, Greece, Turkey, for instance) are already either extinct or doomed to extinction (Sala 1970; Harris 1994). The best we can perhaps hope for is that a Judeo-Spanish koiné, now evolving in Israel—similar to that which developed among Sephardic immigrants to the United States early in the 20th century—may somehow prevail and survive into the next generation.

- Cf. Gerber, J. 1980. Jewish Society in Fez 1450-1700: Studies in Communal and Economic Life. Brill.

- Cf. Schroeter, Daniel J. 2002. The Sultan’s Jew: Morocco and the Sephardi World. Stanford: Stanford University Press,. Arabic edition, Yahudi al-Sultan: al-Maghrib wa-‘alam al-Yahud al-Sifarad (Rabat: Mohammed V University-Agdal, Publications of Faculty of Letters and Human Sciences, 2011).

- https://themaghrebtimes.com/10/03/revisiting-the-moroccan-exception/

- https://www.nytimes.com/1992/04/01/world/500-years-after-expulsion-spain-reaches-out-to-jews.html

- https://www.eurasiareview.com/05032018-emigration-of-jews-of-morocco-to-israel-in-20th-century-analysis/

- https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Morocco_2011.pdf

Bibliography:

Ashtor, E. 1993. The Jews of Muslim Spain. Jewish Publications Society.

Chouraqui, Andre N.1973. Between East and West: A History of the Jews in North Africa. Atheneum NY.

Deshen, S.1989. The Mellah Society. University of Chicago Press.

Gerber, J. 1980. Jewish Society in Fez 1450-1700: Studies in Communal and Economic Life. Brill.

Gerber, J. 1994. The Jews of Spain: A History of the Sephardic Experience. New York: The Free Press.

Geertz, C., Geertz, H., and Rosen, L., 1979. Meaning and order in Moroccan society: three essays in cultural analysis. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press

Kenbib, M. 1994. Juifs et musulmans du Maroc, 1859-1948. Faculté des lettres et des sciences humaines, Université Mohammed V, Rabat, Maroc.

Murphy, C. 2012. God’s Jury: The Inquisition and the Making of the Modern World. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 75.

Schroeter, Daniel J. and Emily Gottreich, editors. 2011. Jewish Culture and Society in North Africa. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Schroeter, Daniel J. 2002. The Sultan’s Jew: Morocco and the Sephardi World. Stanford: Stanford University Press,. Arabic edition, Yahudi al-Sultan: al-Maghrib wa-‘alam al-Yahud al-Sifarad (Rabat: Mohammed V University-Agdal, Publications of Faculty of Letters and Human Sciences, 2011).