Fasting is the most commonly known Yom Kippur ritual. According to a 2016 Pew survey, 40 percent of American Jews and 60 percent of Israeli Jews fast on the Day of Atonement. Of course, fasting is not exclusive to Judaism. It is an ancient practice whose purpose and benefit span across the three Abrahamic faiths—Judaism, Christianity and Islam.

Fasting is mentioned in the Bible and the Koran, and although its practices differ across these religions, they each use food restriction and/or abstinence as a means of growing closer to God through repentance, increased gratitude, mourning and study.

Aliza Bulow, a Colorado-based Jewish educator, and the author and founder of WICK (Women in Chizuk and Kiruv), told JNS that fasting in Judaism generally centers around atonement for previous wrongdoings, mourning or gratitude, in that by abstaining from food, one realizes his/her dependence on God and appreciates the sustenance God provides.

“Fasting that is not on Yom Kippur is so we will feel a sense of lacking,” she explained. “The lacking of food will lead us to feel we are lacking a closeness to Hashem, and we want to get it back.”

She said that the Jewish people see the physical as “a gateway to the spiritual.”

“On Shabbat, we wear pretty clothes, clean the house, enjoy delicious food … because we want to create a physical environment that helps shift our spiritual perceptions,” she said. “Fasting is no different.”

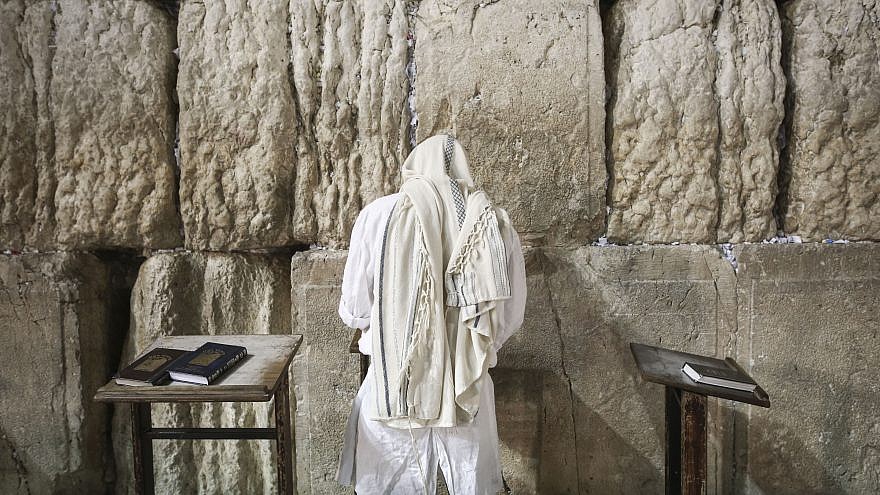

Except on Yom Kippur. This 25-hour fast from sunset to nightfall is solemn, humbling and repentant, but also happy in that repentance brings redemption, said Bulow. On Yom Kippur, which is spent mostly in prayer, fasting aims to elevate Jewish souls to the exalted level of mal’achay hasharait, or “ministering angels.”

“Yom Kippur is our aesthetic day,” said Bulow. “On Yom Kippur, we suffer physically to achieve a spiritual height.”

Fasting in Islam

Islam’s Ramadan, though 30 days, is akin to Yom Kippur, according to Khalil Albaz, the imam of Tel Sheva in southern Israel.

Ramadan is mandatory for every Muslim man and woman above the age of puberty. Albaz added that if a person is sick, elderly, pregnant or nursing, he or she can have permission not to fast, but will need to make it up later by fasting an equal number of days or by giving charity to those in need.

This “sacred month” commemorates the first revelation of the Koran to the Prophet Muhammad. It’s a time when Muslims work on their discipline and moral character, and increase their almsgiving.

“God places much emphasis on being good during Ramadan,” said Albaz. “People give charity for each person in their home, plus an additional 2 percent [or so] for every major asset, including sheep and camels.”

He said that like the month of Elul—during which Jews work to make amends with man and God—throughout the month of Ramadan, all good deeds and charitable donations are considered doubled in God’s eyes.

“You want to do as much good as possible so at the end of the month, when God does an accounting to see how many good deeds you did versus bad deeds, you will skew positive,” said Albaz. By Eid Al-Fitr, the holiday that marks the end of Ramadan, it is expected that Muslims have become improved versions of themselves.

In addition to Ramadan, Muslims also fast on Monday and Thursdays, as well as 13th, 14th and 15th of each lunar month. Other voluntary fasting days include the Day of Ashura (10th day of Muharram); Day of Arafat (ninth day of Dhu al-Hijja, the month of the Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca); and six days during the month of Shawwal, which follows Ramadan.

Fasting in Christianity

Fasting in Christianity varies much more than in Islam and Judaism. Roman Catholics, for instance, define fasting as the reduction of food intake for one full meal and two small meals with solid food intake prohibited between meals. They have two obligatory fast days: Ash Wednesday and Good Friday, though voluntary fasting is encouraged and practiced.

The late American evangelist Bill Bright, who is considered a major catalyst for the modern-day resurgence of the discipline of fasting in the Christian church, said fasting is “a way to align our hearts.”

“I am convinced that when God’s people fast with a proper biblical motive—seeking God’s face, not His hand—with a broken, repentant and contrite spirit, God will hear from heaven,” Bright wrote in his guide to fasting and prayer. “He will heal our lives, our churches, our communities, our nation and world.”

In the Eastern Orthodox tradition, fasting is an important discipline to protect oneself from gluttony, and is generally defined as avoiding meat, dairy products, oil and alcoholic beverages. It is accompanied by almsgiving and prayers; without such acts, it is considered worthless.

Both Catholics and Orthodox Christians observe the Lenten season, which lasts 40 days, starting on Ash Wednesday and ending about six weeks later before Easter Sunday. Lent remembers the fasting of Jesus in the wilderness, and involves atoning in preparation for his death and resurrection at Easter.

In the past, Protestants frowned on fasting, but now it is acknowledged and encouraged as an important spiritual experience among Protestant churches, according to Richard Bloomer, director of the School of Health Studies at the University of Memphis and co-author of The Daniel Cure, a restricted 21-day vegan diet based on a fast in the biblical book of Daniel.

He told JNS that in Christianity, the purpose of fasting is to achieve mastery of spirit over body. Today, many churches are integrating it into their worship, especially in January, to begin the new year through fasting and prayer.

The “Daniel Fast” involves dietary modifications like a purified vegan diet—eating unlimited fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts, seeds and oil while eliminating refined foods, white flour, preservatives, additives, sweeteners, flavorings, caffeine and alcohol. It is derived from the biblical story of Daniel (1:8-14) in which he resolved not to defile himself with the royal food and wine, and requested permission to consume nothing but vegetables and water for 10 days. Later in the book (10:2-3), Daniel again observed a 21-day period of fasting, during which time he had no meat or wine.

“Because individuals traditionally follow the ‘Daniel Fast’ for strict religious purposes to become closer to God during a time of extended prayer, findings have indicated excellent compliance,” said Bloomer.

Bloomer believes that while fasting is often a time of spiritual growth, it can also improve one’s physical health. He said investigations examining the health-related effects of religiously motivated fasts have found favorable health outcomes, including weight and body fat loss, reductions in blood pressure and improvement of fasting blood sugar and insulin levels, which are important for metabolic health.

The author said it remains unclear whether the people of the Bible knew of the health benefits of fasting, but that in the book of Daniel, it is noted that those who did not eat the food from the king’s table performed and looked better, and were healthier.

“Fasting, first and foremost, it should be about spiritual growth and not necessarily about health,” he said. “But getting in great physical condition … is a wonderful side effect.”