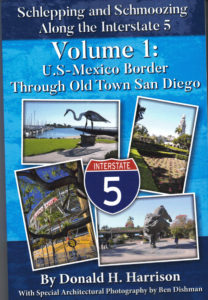

Schlepping and Schmoozing Along the Interstate 5, Chapter 19, Exit 14B (Cesar Chavez Parkway); Chicano Park

Turn left at Cesar Chavez Parkway exit, and murals will be at left side under the overpass. One of the murals is of Freda Kahlo. Turn left at Logan Avenue to see more murals of Chicano Park.

In 1970 Barrio Logan neighbors organized a massive demonstration protesting the State of California’s plans to build a Highway Patrol Station on the nearly eight-acre property under the eastern approach to the San Diego-Coronado Bridge. Linking arms, they refused to permit bulldozers to move the earth. They demanded that the land, previously promised to the community as a park, in fact be used for that purpose. The State of California relented and Chicano Park was born.

Three years later, brightly colored murals began to appear honoring Mexican and Mexican-American history. Later, subject matter expanded to incorporate figures from other Spanish-speaking countries. At first contemptuously dismissed by Anglo critics as graffiti, the more than 80 murals painted on pylons and abutments eventually were recognized as an important, historic outdoor art venue, winning plaudits and federal grants for Chicano Park’s further improvement. The U.S. Department of the Interior recognized Chicano Park as a National Historic Landmark in 2017.

The Mexican artist Frida Kahlo (1907-1954) is the subject of several murals at Chicano Park. Modern genealogists say that she was the daughter of a mother of mixed indigenous and Spanish descent, Mathilde Calderon y Gonzalez, and a German Lutheran father, Guillermo Kahlo. However, Frida herself always insisted that her father, who was an important influence on both her life and her art, was actually Jewish.

She identified with Jews in other ways, by voicing anger at how they were discriminated against in the United States, and by portraying Jewish themes in the masterpiece known both as “Moses” and as the “Nucleus of Creation.” Julien Levy was the first art dealer to exhibit her work at his New York City gallery, and Hollywood actor Edward G. Robinson, Peggy Guggenheim, Helena Rubenstein, and Mexican film producer Jacques Gelman were among her early collectors. The San Francisco medical doctor who was her trusted confidante, Leo Eloesser, was another important Jew in her life.

Her attraction to Jews also was demonstrated by her extra-marital affairs with Hungarian-American photographer Nickolas Muray, her art dealer Julien Levy, Columbia art professor Edgar J. Kaufmann, and Leon Trotsky, the Marxist theorist. She met Trotsky and offered him refuge at La Casa Azul [the Blue House], the home she shared with her philandering husband and famed muralist Diego Rivera, after Trotsky fled to Mexico as a refugee from the Stalinist government of the Soviet Union. Trotsky and his wife Natalia moved from the Kahlo-Rivera home 16 months before his assassination on August 20, 1940, by a Soviet agent who smashed Trotsky’s head with an ice pick.

After arriving in Mexico in 1891 at age 19, Kahlo’s father (1871-1941) changed his name from Carl Wilhelm Kahlo to Guillermo Kahlo. He applied for Mexican citizenship three years later. He was a photographer who frequently used Frida as a subject. Like his daughter, he also was fond of self-portraits, some quite daring, including a nude study of himself as seen from behind. His main work, however, focused on the architecture and churches of Mexico.

Frida was stricken with polio at age 6, and the shorter and thinner leg that resulted from the disease would be the least of her medical troubles. Twelve years later, returning home from school by bus, she was the victim of a collision with an electric streetcar. She was pierced by an iron handrail, injuring her spine, pelvis, abdomen, uterus and foot—and it was a miracle that she hadn’t been among the dead in that accident. She was bedridden for three months, and periodically her constant pain forced her to undergo follow up surgery and further convalescence in bed. It was during these convalescences that Frida would paint some of her self-portraits, utilizing an easel that sat at the foot of the bed, and a mirror with which she could study her image. The following year, when she was 19, she and Diego Rivera, 20 years her senior, began a relationship that would lead to marriage in 1929. The two artists loved and taunted each other with their extramarital affairs, nevertheless coming back to each other, even after a divorce. In some cases, Frida’s affairs were with women – a fact that later led to her being celebrated in the LGBTQIA community.

Although Rivera was more famous than Kahlo, her fame grew. After Rivera was commissioned to paint murals in 1931 for the Detroit Institute of Arts, they spent a year in the Motor City –not at all to Kahlo’s liking. She disliked the antisemitic Henry Ford and his son Edsel, with whom they socialized, and expressed dismay over how Jews were excluded from Detroit’s better hotels. She felt more at home in New York City, where Rivera painted a mural for the New Workers School, but grew homesick for Mexico and persuaded Rivera that they should return at the end of 1933.

Back in Mexico, Frida had her most productive period as an artist, switching to large canvasses from the small portraits on tin sheets she had previously favored. Best known for her 55 self-portraits in a body of work that included 143 paintings, the individualistic Freda identified with Mexican folkloric culture and was identifiable by her colorful dress, her single eyebrow stretching over both eyes, and a slight mustache, which she declined to ever shave.

A Communist who painted portraits of both Karl Marx and Josef Stalin, Kahlo hated Nazism and some commentators believe that she made up her father’s Jewish religion as a way to disassociate herself from Nazi Germany.

After Frida’s death in 1954, her fame continued to grow. She was celebrated by feminists, Chicanos, the LGBTQIA community, and art historians. The Mexican government declared her works national treasures, prohibiting them from being removed from that country. Her life has been the subject of numerous books and movies, the most celebrated thus far being Frida that starred Selma Hayek in 2002. Frida’s image is instantly recognizable all over the world.

After Frida’s death in 1954, her fame continued to grow. She was celebrated by feminists, Chicanos, the LGBTQIA community, and art historians. The Mexican government declared her works national treasures, prohibiting them from being removed from that country. Her life has been the subject of numerous books and movies, the most celebrated thus far being Frida that starred Selma Hayek in 2002. Frida’s image is instantly recognizable all over the world.

*

Next Sunday, May 15, 2022: Exit 15A (J Street): Petco Park.

This story is copyrighted (c) 2022 by Donald H. Harrison, editor emeritus of San Diego Jewish World. It is a serialization of his book Schlepping and Schmoozing Along Interstate 5, Volume 1, available on Amazon. Harrison may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com

Republished from San Diego Jewish World