Passover is called the holiday of freedom for good reason. Every year for the last 3,000 or so years—wherever we are and in whatever form of bondage we find ourselves—we manage to celebrate our liberation after 210 years of serving Pharaoh, complete with the horror of watching our infant sons thrown into the Nile.

Passover, or Pesach in Hebrew, runs this year from the night of Friday, March 30, through Saturday, April 7 (after Shabbat). It is, after all, the Jewish holiday most redolent of freedom. In the space of a single seder night, we climb from the lowest of the low—the degradation of Egyptian enslavement—to the highest of the high, as no less a power than G-d partners with surviving infant son Moses to save the Israelites.

And ever since then, generation after generation, the Jewish people have placed a high premium on freedom.

Exactly how high?

In December, hundreds of well-wishers danced in the streets, both outside the jail and in front of his home in Monsey, N.Y. when Sholom Mordechai Rubashkin—chief executive officer of the Agriprocessors kosher-meat slaughterhouse and packing plant in Postville, Iowa—was released after eight years of incarceration of an original 27-year sentence for fraud.

Though not a pardon (Rubashkin’s conviction stands, along with a supervised release and restitution requirement), the freedom from imprisonment was enough to get Jews on their feet, says Rabbi Yom Tov Glaser, who teaches at Aish HaTorah in Jerusalem.

The same week Rubashkin was released, another prisoner (who wasn’t Jewish) was freed after serving 32 years for a crime he never committed, according to the rabbi. “Who came to get him? His lawyer and his mother. Who came to the jail to celebrate with Rubashkin? Hundreds of strangers dancing in the street. This is how we greet another Jew’s freedom.”

Jews also partied exuberantly in 2011 at the release of Israeli soldier Gilad Shalit, who had been imprisoned for five years by the terror organization Hamas.

Shalit, the first IDF soldier to be released alive in 26 years, was the subject of an intense campaign, with his parents sitting on a busy Jerusalem thoroughfare day after day advocating for their son’s release. The exchange raised questions, as well as celebrations: Shalit was traded for 1,027 convicted terrorists, responsible for the deaths of 569 Israelis—the highest price Israel has ever paid for a single soldier.

And there was jubilation aplenty at the 2015 freeing of Jonathan Pollard (also not complete; he remains under modified house arrest) after 30 years of a life sentence for spying for Israel.

‘So lucky to be alive’

Although their numbers drop daily, Holocaust survivors can still testify to the sweet taste of freedom.

Agi Geva was 14 when the Nazis invaded her native Hungary and sent her to Auschwitz. “In the camps, we didn’t know what day it was, so we had no awareness of holidays,” she says 74 years later. With her sister and mother, she survived a death march at war’s end with little food or water, and rags around their feet instead of shoes. But four years later, at 19, she found herself in Israel experiencing Passover—and freedom—in ways she never dreamed possible.

“Passover we spent at my sister’s kibbutz near Hadera,” says Geva, now 87. “It was very emotional, very uplifting, with 400 people together at the seder. I couldn’t believe I was so lucky to be alive and to be in Israel.”

Now living near Washington, D.C., Geva has volunteered at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum for 16 years.

“I tell the students what I tell my children and grandchildren—that there is nothing I appreciate more than freedom,” she says. “We Jews have lost it so many times that we have such a love of freedom. When the Nazis came, we were not free anymore; we were forced to wear the yellow star, live in the ghetto, do what we were told.”

So sure was she that she would die a prisoner that she “could not even imagine freedom.”

Geva says she kept her story private until she heard about Holocaust-deniers. “So now, I tell my story to as many people as I can. I show them the numbers on my arm. I’m just grateful I can still do it.”

‘Thank you for bringing us here’

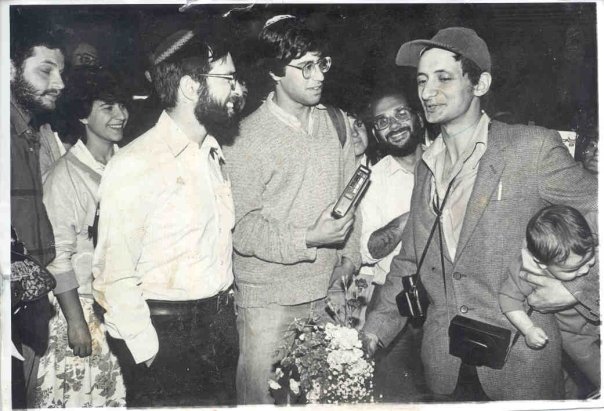

Refuseniks like Marina Kitrossky know the value of freedom, too. From the time she and her husband, Levi, applied for a visa to leave the Soviet Union for Israel in 1979, doors began to slam shut all around them as they were banned from jobs and university, with the only work her chemist husband could find in a factory producing known toxins.

A seder? If you had one, you better not let anyone know. “The phones were tapped, so we needed to be very careful,” she says.

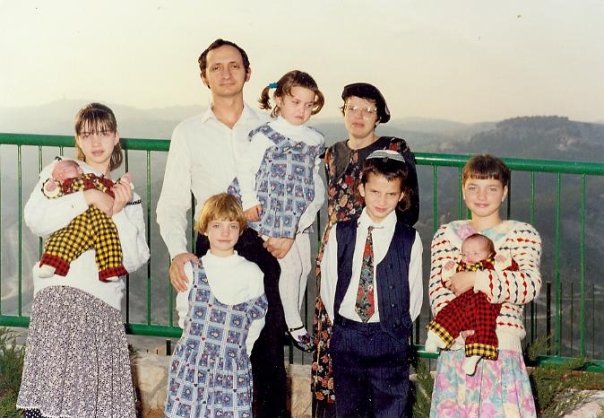

It took eight years for those doors to swing open with Perestroika. “When we got to Israel with our three children, we were so happy to be able to celebrate openly, to not be afraid anymore of what our 5-year-old might say in public,” recalls Kitrossky.

These days the 60-year-old runs Machanaim (Hebrew for “two camps”), a Jerusalem-area Jewish-education center for Russian-speakers. “Living in Israel, it’s strange to recall what it was like in the Soviet Union; everything Jewish was so clandestine,” she says. “It took us a year to get used to being openly Jewish.”

Kitrossky’s children (now seven in all) wrote her a song for their mother’s 60th birthday. The refrain? “Thank you for bringing us here.”

And even in these times of relative peace, the story of liberation continues to resonate powerfully with Jews everywhere, insists Sarah Bassin, associate rabbi of Temple Emanuel of Beverly Hills, Calif.

“We can learn the lesson of the Israelites who, before they could be freed, had to acknowledge their situation and cry out to G-d to save them,” she says. “We all need to see ourselves in the Passover story—our eternal narrative of coming out of Egypt, Mitzrayim, a narrow place.”

“It’s often compared to coming out of the birth canal,” she adds, “and on the other side is freedom and life.”