The Academy Awards ceremony—with all its traditional Hollywood hype and international attention—is set to take place in Los Angeles on March 2. The Oscars represent the best talent the big screen has to offer, and the annual extravaganza has become a symbol of fashion, glitz and glamor. It offers a global stage for the stars to parade their dazzling designer gowns and over-the-top outfits to their adulating admirers.

Apparently, the famous after-party is where protocol and etiquette are abandoned in a competition of who can be daring enough to show as much flesh without getting arrested for indecent exposure.

I think the Oscars—and Hollywood, in general—have become equally emblematic of talent and trash. We can respect and admire art and talent, and, of course, a good movie with a meaningful message can leave impressions for life on millions of minds and hearts. And at the same time, it is all so superficial, so empty. Are we celebrating art? Perhaps. But so much of the periphery seems to be dominated by an outer beauty and an inner emptiness.

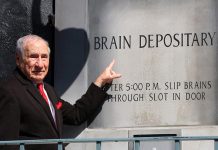

Hollywood is hollow. I see bright lights and blank faces.

How many celebrities can we hold up to our children as role models? This one died of an overdose; that one is in jail for sexual harassment. How many die of old age? How many have good marriages or have celebrated a golden wedding anniversary? (I’ll settle for silver!) The divorces are certainly much more spectacular than the weddings.

None of it seems real. Never mind fake news, it’s a fake world in La-La Land.

Now, let me share a Talmudic story.

Rabbi Gamliel was a first-century sage, and the head of the Yeshivah and the Sanhedrin—the Jewish Supreme Court based in Yavneh after the destruction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem. It happened that the sages felt it necessary to depose Rabbi Gamliel from his position, as they considered him to have been demeaning to his colleague, Rabbi Yehoshua. He was replaced by Rabbi Elazar ben Azariah, who appears prominently in the Haggadah on seder eve every Passover.

The Talmud recounts that on the day Rabbi Gamliel was replaced, hundreds more benches were needed in the study hall for all the new students who now flocked to study Torah.

Why? Because the rabbi was very strict in his admissions policy.

He insisted that to be accepted in the yeshivah, a student needed to be tocho k’baro. It means that his inside (his thoughts and feelings) must be like his outside (his conduct). Not only his outer behavior needed to be appropriate but also his inner character. If not, the student wouldn’t be accepted.

When Rabbi Gamliel was replaced by Rabbi Elazar, the admissions policy changed dramatically; anyone who wanted to study Torah could now join.

They dismissed the guard at the door, and permission was granted to the students to enter. On that day, many benches were added to the study hall to accommodate the numerous students. One opinion stated that four hundred benches were added to the study hall. And one said: Seven hundred benches were added to the study hall (Brachot 28a).

I suppose that we can debate which admissions policy is best. The most famous yeshivahs and universities today have stricter admission policies than most. Indeed, their graduates excel. On the other hand, there is a case to be made for an open-door policy that would be inviting for every student to learn and grow in Jewish wisdom and practice.

At any rate, I am sharing this story to give you a taste of the values and standards that our sages wanted their students to aspire to. To appear pious and devout on the outside, and be crude and callous on the inside is dishonest, hypocritical and unbecoming for a student of Torah.

Personally, I would advocate that the broadest admissions policy be welcoming to every Jew, young or old, to get a taste of Torah and allow it to enrich their lives. At the same time, we need to aspire higher and aim to develop students who will embody the lofty ideals of traditional Torah personalities in their chosen lifestyles. We need to be honest, consistent, wholesome and genuine. Creating a religious impression while being a degenerate hedonist is dishonest. Such a life is a lie; it’s not real.

We can find this message in Parshat Terumah this week. Moses is instructed to build the Mishkan—the very first Sanctuary for God—in the wilderness. It would house the sacred vessels that would later be in the Temple in Jerusalem. The holiest of all was the aron, the ark that contained the Tablets of Testimony with the Ten Commandments and was placed in the Holy of Holies.

The ark was to be made of acacia wood, and coated with gold on the inside and outside. How did Betzalel, the young genius who was the architect and designer of the Mishkan, construct the ark? Rashi tells us that he made three arks, one slightly larger than the next. The largest and smallest were made of gold, and the middle one was made of wood. He placed the wooden ark inside the larger golden ark and then the smaller golden ark inside the wooden ark. So, he now had a wooden ark coated with gold on the inside and the outside. Gold, wood, gold—it was brilliant in its simplicity.

The message? We need to be pure gold outside and inside. We should always try to be honest, wholesome and holistic. And we should produce students who are sincere, genuine and real—not plastic, barren or bare. Their outer personalities and their inner characters should be alike, a match, and consistent.

Hollywood produces lots of talent. Yeshivahs produce real people, inside and out.