The late Holocaust survivor, human-rights activist and Nobel laureate Elie Wiesel became the first modern Jew to have a bust of his face sculpted into the stonework of the Washington National Cathedral’s Human Rights Porch on Oct. 12, the last to be installed among four luminaries such as Mother Teresa and Rosa Parks.

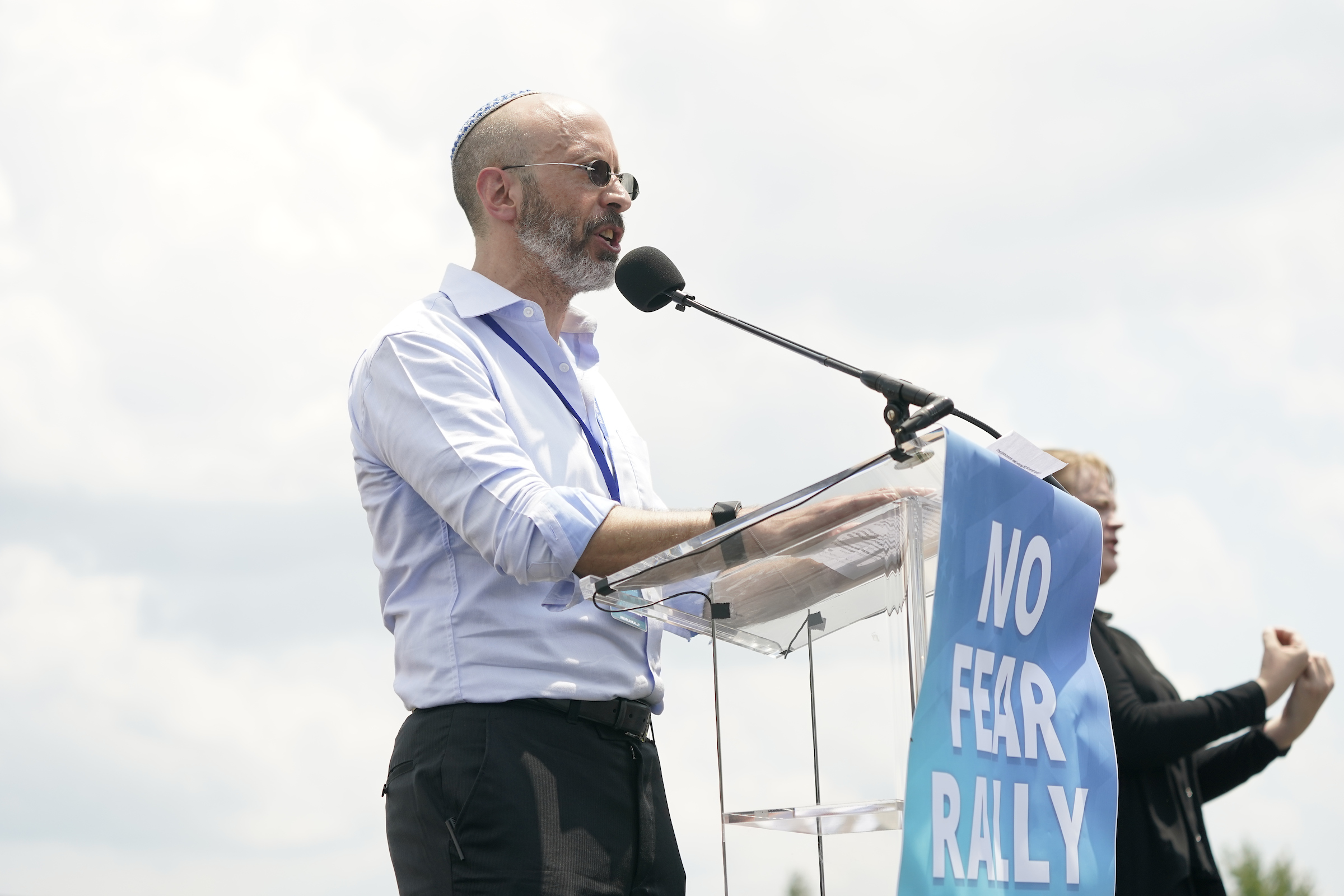

A small, invitation-only audience attended an unveiling ceremony lasting more than two hours, where Wiesel was eulogized by distinguished individuals such as former U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright; historian John Meacham; Rabbi Irving “Yitz” Greenberg, former chairman of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Council; Sara Bloomfield, director of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial and Museum; Mehnaz Afridi, director of the Holocaust, Genocide and Interfaith Education Center; Wai Wai Nu, founder of the Women’s Peace Network; and Rabbi David Saperstein, former Ambassador-at-Large for International Religious Freedom.

“His global activism was rooted in and fueled by his belief in a just and merciful God,” said Hollerith.

Wiesel’s speech focused on his father’s Judaism, as well as support for the State of Israel, which he inextricably linked. In his speech, Wiesel, 49, asked questions of his father, who died in 2016, that illuminated those beliefs less often considered by the secular world.

“Today, you are recognized for speaking out against silence, but sometimes, I see people quote your admonition against silence as an excuse to scream at others with contempt, self-righteousness and anger. You never humiliated, ridiculed or screamed,” said Wiesel. “But what’s hardest for me is seeing those who read your books cry for the dead Jews, quote your protests against injustice, and then condemn in the most unforgiving terms the 6 million Jews living in Israel who refuse to ever again depend on the world to rescue them.

“No longer stateless and defenseless, these Jews, my brothers and sisters, face difficult circumstances and sometimes impossible choices. For this, they are held to a different standard than any other nation on earth by America’s elite.”

Wiesel, a successful businessman who has in recent years campaigned against anti-Semitism and anti-Zionism, spoke to JNS by phone on Tuesday about the experience, as well as current issues with anti-Semitism and Jewish unity.

The interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Q: How do you feel about your father being honored in such a way, being the first modern Jew in the cathedral?

A: It’s a profound measure of respect, right? For me, the cathedral was presented to me as a multi-faith institution. I know that that’s not 100 percent right because it is primarily Episcopalian. But the thing that ultimately really moved me was that it’s an American institution, and my father was a passionately loyal and fervent citizen.

I could tell you about some of the conversations I’ve had with him; you might be surprised what positions he took on some things, but he was such a proud American.

You have to remember, this country offered him citizenship when nobody else had.

When he arrived, he was still on a journalist visa, and he had been in a very bad traffic accident, and I think he was worried he’d missed the opportunity to renew his visa. He went to the customs office, and they said, “You know, you don’t have to renew your visa. You could become a citizen.”

Now, imagine that happening in this day and age. But that was a very powerful moment for my father. He really treasured being an American.

So to have him enshrined in such a powerful American institution is quite meaningful.

Q: Most people in your place would have probably spoken about what your father witnessed and his accomplishments, but you chose to ask questions of your father and society, which was a very interesting take, and then also linked your father’s work closer to the Israel issue, when some people keep them separate for such an occasion. Why did you decide to do that?

A: I wanted to provide some balance. You know, one of the things that I was most worried about is this concept that others will tell the story of my father and who he was. But I know what was most important to my father—because he told me regularly—and that was to be a good Jew. And for him, being a good Jew, that was the ultimate thing to unpack. There were so many pieces to that.

For him to be a good Jew meant to be an observant Jew. For him to be a good Jew meant to be someone connected to Israel and to the Jewish people and to Jews all around the world, whatever their needs are. And for him to be a good Jew meant to be a good person and to be an activist, and to stand up for other people and to broadcast the values that he derived from his faith. You know, my sense was that we’re at a time in American history where my father is mostly remembered only for the third.

I think that my father is remembered for his accomplishments on the diplomatic stage, for having been a human-rights activist. And it’s really only those who knew him or who read him closely or listened to his lectures, that acknowledge what a profound part of my father’s identity was wrapped up in being a Jew with all that it meant—the Zionism, the Yiddishkeit, all of it.

Had every other speaker gotten up there and talked about my father as a Jew, I would have balanced it out by talking about my father as a global human-rights activist. But I had a sense that the way that the program was being constructed was very much going to be about my father as a universalist, and thus I felt it was to me to inject that particular.

Q: I understand that you’re spending a large part of your time now trying to get politics out of the discussion of anti-Semitism, is that correct?

A: I don’t know that you can get politics out of the discussion. I think it’s more a question of recognizing that it exists across all parts of the political arena.

Q: Do you think today’s polarization is the worst you’ve seen?

A: Yes, but I’m older than I was, so I probably notice things more. I’m more sensitized to it. I mean, I’m sure that there were very tough times for us during my lifetime that I just didn’t appreciate as keenly. But yeah, it feels very bad now. And I think it may feel particularly bad because we’re at risk to losing so many of our own people.

You look at some of the polls and it’s clear that we’re not doing a great job with our next generation of American Jewry, getting them to understand very basic things.

Forget the Holocaust-education piece—the fact that so many Americans don’t know what Auschwitz was. But with words to Jewish identity among Jews, these polls come out that suggest that there are too many Jews out there who would agree with the statement that Israel should not exist, who would agree with the statement that Israel is guilty of genocide. So it somehow feels worse to me now in that we’ve even lost the plot a little bit with some of our own people.

A: Are you worried about this embrace, especially among some Democrats and a lot of young progressives, of calling Israel an apartheid state?

Q: Of course, I’m worried, and it’s such a shame because I think if you look at Jewish activism over the past century in this country, so much of it has been aligned with progressive ideals. And the thought that causes that we agree with—whether it’s the importance of voting rights, whether it’s the importance of gender or equality, or for the LGBTQ community to not feel persecuted—whatever the issue is Jews have, by and large, been on the right side of these things.

And then to discover that within these communities, this hate can take hold. I think there’s really two parts of it—one is that there are definitely conscious actors out there looking to seed lies and hatred among people that are very impressionable and very passionate.

And then I think that there is a fair amount of ignorance. We’ve gotten intellectually lazy as a country, and Israel-Palestine is hard, so who wants to sit there and do the work to understand the truth of what it means that Israel has had to fight defensive wars.

Q: You just told me that it’s impossible to get this issue depoliticized, so how do we move on? What are your suggestions for attacking anti-Semitism and anti-Israel sentiment?

A: I think we have to do what we’ve been doing all along, which is to call it out when we see it. But we also have to not give up and cede territory. You know, it might be so tempting, particularly on the more progressive side of politics to say, “This feels like a betrayal. You know what? We’re not going to engage in these causes anymore.” But I think that’s a mistake, and I think that the credibility that we earn, rightfully, by being there for the most important causes in this country will over time show our allies as opposed to telling them that our values truly are in sync.

So that’s why I very much believe that we can’t cede the progressive territory. Those of us who believe in some of these very important causes need to continue standing up for them and do so as Zionists. And we don’t need to hit them over the head with it, but people need to understand that we’re not going to be excluded from any part of the political sphere where we feel we want to operate.

Q: Anti-Semitism has been around for thousands of years and in every culture, whether people lived besides Jews or not. I’m assuming the problem of totally getting rid of anti-Semitism is not possible. How else could we approach the issue if we cannot totally eradicate it?

A: There are all sorts of spheres in which one can operate. In the political sphere—what I said earlier—we have to be true to our values and show up for the causes we believe in, and ultimately, our allies will see that we’re showing, not telling.

But I also think it’s true in the personal sphere. And you know, it’s interesting, voices as diverse as the Chabad-Lubavitch movement and [former New York Times editor and columnist] Bari Weiss speak about this, how important it is to be pro-Semitic. The best way to be anti-anti-Semitic is to be pro-Semitic. And that means if you’re raising a family, raise them a little bit more Jewish than you otherwise might. If you aren’t keeping Shabbat dinner, keep Shabbat dinner. If you haven’t been to shul in a long time, go to shul. Talk about Israel at the dinner table. Connect to a family member in Israel or schedule a trip once COVID allows.

I think that there is a lot of truth in that the best way to fight against the darkness is to just be the light. And there’s so much in our tradition and in our peoplehood to appreciate and explore, that I think once people get started a little bit down that path it becomes an easier path to travel.

Q: Do you think that it’s possible to eradicate it? What’s your end goal?

A: There’s a commentary that says, “Esau hates Jacob.” And it’s just the way it is. I don’t know if you can ever fully erase it. But I don’t know that we need to fully erase it. We need to erase it enough that it doesn’t prevent us from living the lives that we want to lead and, thank God, we have a State of Israel now where the Jewish people have a point of security that we haven’t had in 2,000 years. So I think the expectation that we’re going to eliminate it completely is too idealistic.