As the Good Book says …

The musical “Fiddler on the Roof” first proclaimed Shalom Aleichem to Broadway audiences in 1964, with Zero Mostel belting out the iconic “If I Were a Rich Man” song as Tevye the Dairyman, the father of seven daughters (five of whom have roles in the play). Bea Arthur played Yenta in the production, whose Boris Aronson-designed sets evoked Marc Chagall’s shtetl paintings.

Sixty years later, Tevye’s misquotations muddying the Torah, coupled with his witty megalomania, have reverberated through the halls of American theaters in countless productions. The play is said to be performed daily somewhere around the world since it first opened on Sept. 22, 1964, according to the 2019 documentary “Fiddler: Miracle of Miracles.”

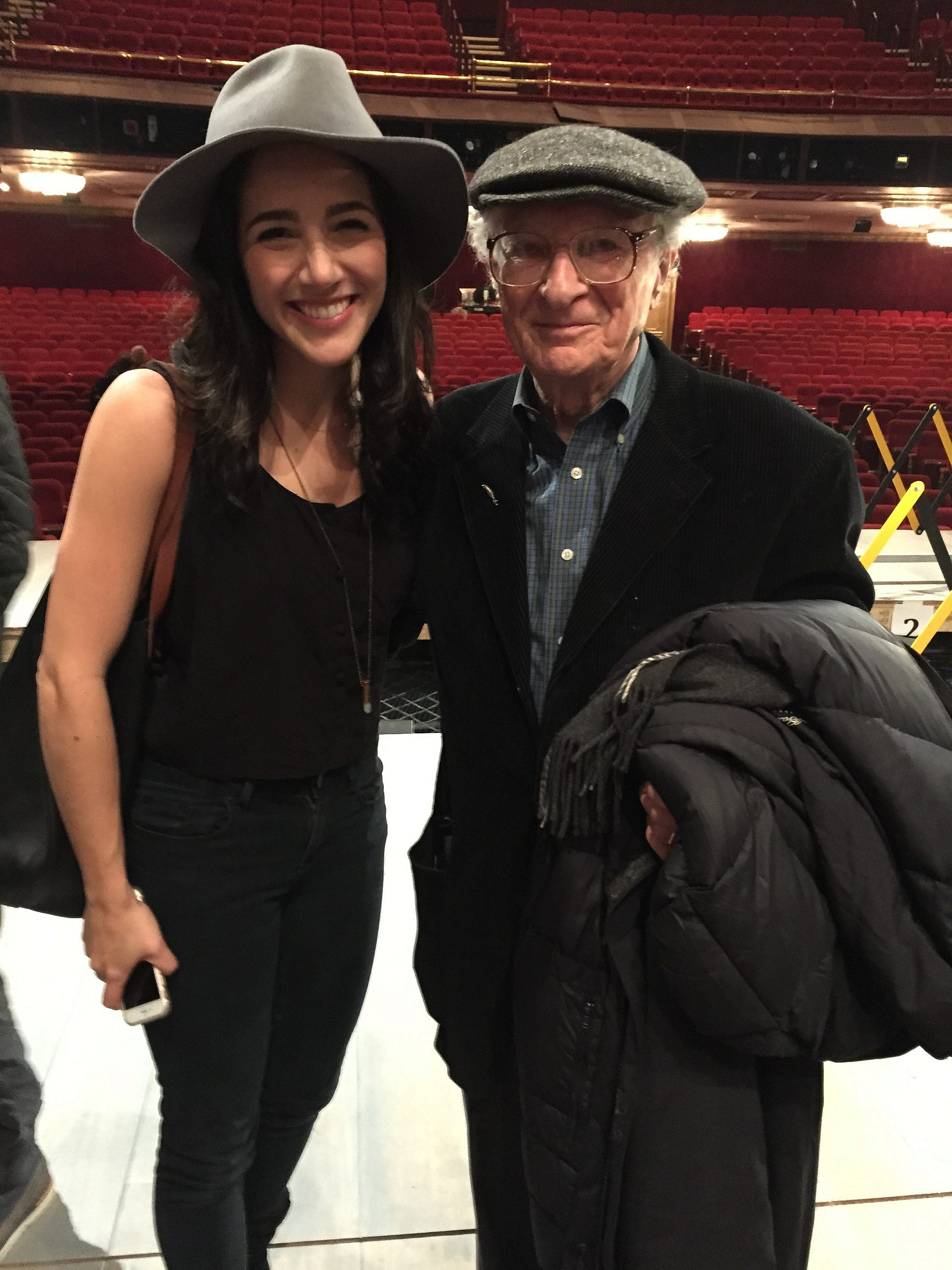

Samantha Massell, who played Tevye’s second daughter Hodel in the 2015 Broadway production, told JNS the play “is a flawless musical.”

The play is “one of the most recognizable titles in the musical theater canon” and “one of the few that has made an indelible mark on American culture,” she said.

The original Broadway version, with Jerry Bock’s music, Sheldon Harnick’s lyrics and Jerome Robbins’s choreography, ran for eight years, winning nine Tony Awards in 1965, including best musical, score, direction and choreography.

Alfred Molina, Theodore Bikel and Harvey Fierstein have performed Tevye over the years in the play based on Sholem Aleichem’s Tevye and His Daughters.

As the play approaches the age at which it is entitled to a senior discount, it has lost three key figures in the past year.

Norman Jewison, who directed the 1971 film version, died on Jan. 20 at the age of 97. Harnick, the songwriter, died at 99 on June 23, 2023, and Chaim Topol, who played Tevye in the film, died at 87 on March 8, 2023.

Tevye jokes in the play, after inventing an appearance in his dream of Grandmother Tzeitel, that she looks very good for a woman who had been dead 30 years. What the next 60 years might look like for “Fiddler,” as it approaches the rabbinically endorsed, ripe old age of 120, is an open question.

An inhospitable climate

Ruth Wisse, professor emerita of Yiddish literature and comparative literature at Harvard University and distinguished senior fellow at the Tikvah Fund, is bearish on the future of “Fiddler.”

Wisse, who created an eight-part series of online Tikvah classes about “Tevye the Dairyman,” told JNS that the tales were personal to Sholem Aleichem.

The writer described his “responsibility to care for children who go their different ways, writing it at a time of great generational conflict,” Wisse said. “There are many such periods in history, but some are more acute than others. This is a recurring subject.”

The show addresses “the idea of a minority that is under siege,” in this case Jews. It has a timeless aspect to it, save perhaps as antisemitism surges after Hamas’s Oct. 7 terror attack on Israel.

“You tell me what’s happening in America,” Wisse told JNS, noting that she is sure that many university theater departments wouldn’t dare stage the play today.

“Will it play to the next generation? In the current political atmosphere?” she asked. “I don’t think so.”

Universalized Americana

Set in the fictional shtetl of Anatevka in the early 1900s, “Fiddler” revolves around the poor milkman Tevye and his struggles to maintain Jewish tradition in changing times, culminating in his older daughters’ decisions to seek love outside of arranged marriages, and in one case, outside of the Jewish community.

Scholars have said that the play reflects American struggles with tradition and modernity.

Massell, the actress, told JNS that “Fiddler” is iconic Americana, while it has also found universal appeal. She noted that Joe Stein, who wrote the original play’s book, was talking with the producer of the first “Fiddler” production in Japan. The latter asked Stein if Americans truly understand the play, given how Japanese it is.

“This story is so timeless. Yes, it is an intrinsically Jewish story, but the themes of tradition, family and assimilation are relevant across so many cultures,” Massell said. “Everyone can relate.”

Sholem Aleichem appears to have created the Tevye character in 1894, which means the dairyman gets 130 candles on his cake. The writer penned the final Tevye story in 1914 (110 years ago), and “Tevye and His Daughters” became an off-Broadway musical in 1957. In 1959, New York’s Channel 13 aired “The World of Sholom Aleichem” in its show “Play of the Week,” starring Mostel.

The film critic Jan Lisa Huttner, who has published two books on “Fiddler,” notes differences in the iterations of “Fiddler.” The written stories have a male matchmaker with a minor role, not Yenta, for example. She told JNS that it is “to the credit of the creators” that they managed to universalize the play, whose financial backers thought it was too parochial for American sensibilities when it was first pitched.

“It has universal truths,” Huttner told JNS.

“Parents, they have a certain image in their mind of what their children are going to be, and they’re responsible for them in many ways, shaping and molding that child,” she said. “Children on their own encounter strengths and weaknesses and everything.”

The story must also be viewed in the context of history, she urged.

“In periods of great turmoil, there’s going to be different turns of events in significant ways, and that’s what ‘Fiddler’ captures,” she said. In the story, that turmoil included tsarist marauders that disturbed, or pogrommed, Jews.

Too much ado about tradition?

Lovers of the show think of tradition as a central and universal theme; “Tradition,” which notes that a tradition-less people would have lives as shaky as a fiddler on a roof, is among the play’s most admired songs.

Many Orthodox Jews, however, view the production as advocating for assimilation, or at least rethinking Jewish religious practices and values.

Huttner, who consulted on the documentary “Fiddler: A Miracle of Miracles,” thinks tradition is a minor plot element.

“Excuse me, that’s in the first five minutes. You’ve got another three hours to go,” she said. “At the end of it, it turns out that our lives are as unstable as the fiddler on the roof. We’re all in the balance.”

Alisa Solomon, who directs the arts and culture concentration at Columbia Journalism School, told JNS the play “is beautifully built. The songs are wonderful. It’s completely emotionally engaging.”

“For us Jews, we think of the show as speaking directly to us, addressing the things that we recognize and identify with—and that’s all true,” she said. “At the same time, it’s traveling on a parallel track of universalism, where children are making their own lives, and moving away.”

Solomon, who is the author of the book Wonder of Wonders: A Cultural History of Fiddler on the Roof, added that historical forces, “for better and worse, often worse, are pressuring different groups of people to have to uproot their lives.”

“All of those things are always going on,” she said. “In the show, it gives us windows into the experiences, feelings and meanings of all of those things.”