Tel Aviv University researchers have found a method of preventing memory deterioration in the animal model of Alzheimer’s disease, the university announced on Tuesday.

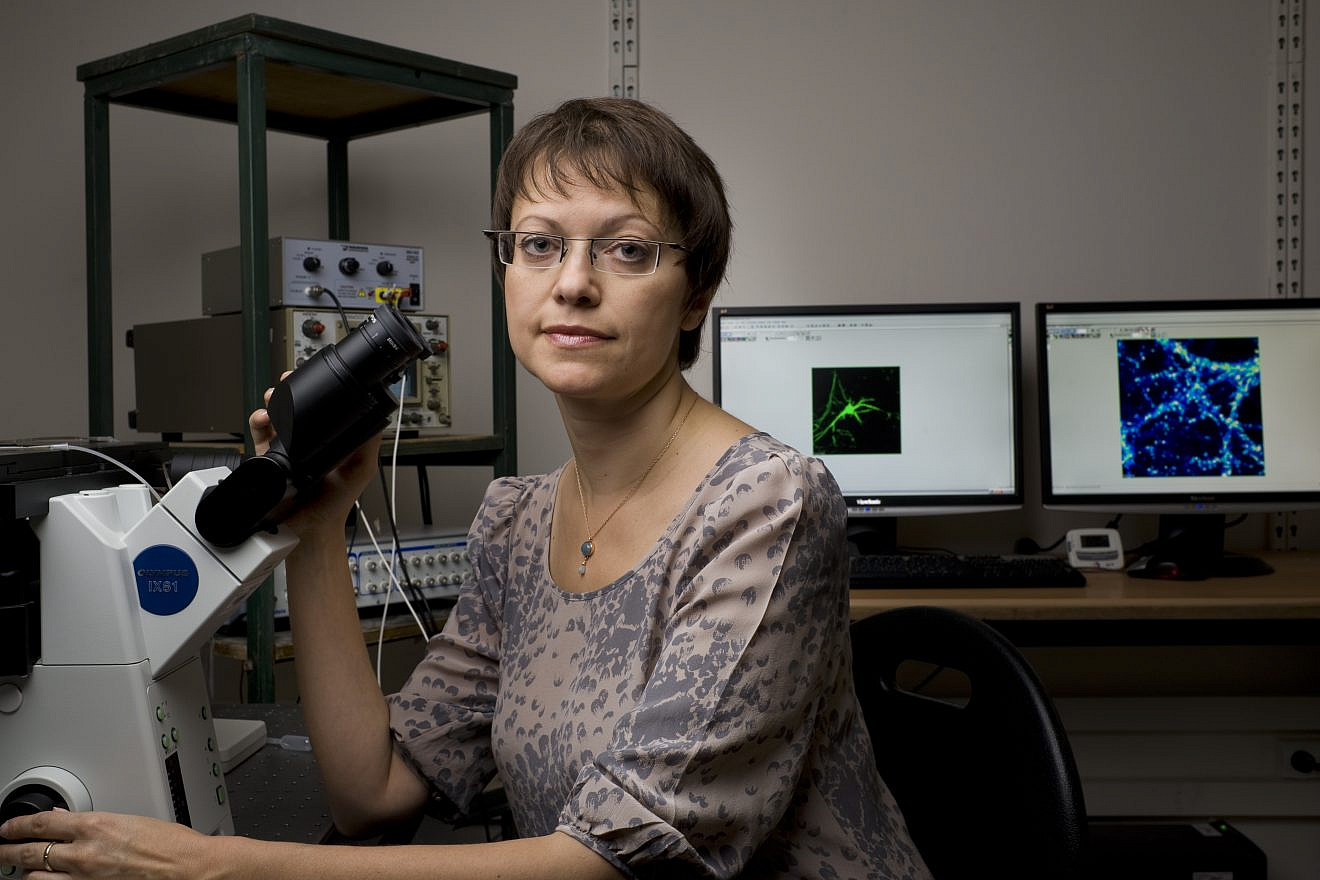

The study, conducted in collaboration with the Hebrew University and published in Nature Communications, builds on the discovery by TAU professor Inna Slutsky’s lab in 2022 of a brain pathology in the animal model that long precedes the onset of Alzheimer’s symptoms.

According to Shiri Shoob, the doctoral student who led the current study, these physiological changes, which include an accumulation of amyloid-beta deposits and abnormal accumulations of tau protein, as well as a decrease in the volume of the hippocampus, can show up 10 to 20 years before the onset of the cognitive decline and memory impairment more commonly associated with the disease.

During sleep, and especially during sleep induced by general anesthesia, the pathology causes “silent seizures,” which look like an epileptic seizure in terms of brain activity. Normally, activity in the hippocampus decreases during sleep and under anesthesia.

Believing that there are mechanisms compensating for this pathology during wakefulness, thus prolonging the pre-symptomatic period of the disease, in the current study the team mainly focused on deep brain stimulation (DBS) using electrical signals to the nucleus reuniens.

The nucleus reuniens is located in the thalamus, which is responsible for sleep regulation, and is a key component of a network of structures in the hippocampus and cortex, playing a vital role in cognition.

“When we tried to stimulate the nucleus reuniens at high frequencies, as is done in the treatment of Parkinson’s, for example, we found that it worsened the damage to the hippocampus and the silent epileptic seizures,” said Shoob. “Only after changing the stimulation pattern to a lower frequency were we able to suppress the seizures and prevent cognitive impairment. We showed that the nucleus reuniens had the ability to completely control these seizures. We could increase or decrease the seizures by stimulating it.”

According to Slutsky, epidemiological studies have provided evidence for a link between aging and a phenomenon called postoperative cognitive dysfunction (POCD), in which cognitive problems arise following surgery under general anesthesia.

“In young people, the symptoms usually pass very quickly, but in older people, the chance of cognitive impairment increases, and it may last a long time. Our research indicates a potential mechanism underlying the phenomenon,” she said.

“We found that suppressing the thalamic nucleus reuniens—by pharmacological or electrical means—successfully prevented both pathological activity in the hippocampus during anesthesia and cognitive impairment following anesthesia,” she added.

“In addition, we identified a relationship between certain pathological activity in the hippocampus during anesthesia in the presymptomatic phase of Alzheimer’s to memory problems in a more advanced stage of the disease. This indicates a potential [method] for predicting the disease in the dormant state, before the onset of cognitive decline.”

The researchers hope that their findings will speed the start of clinical trials in humans, potentially leading to advancements in early detection of Alzheimer’s, prevention of dementia symptoms associated with the disease, and progress in treating POCD.