In a greater attempt to be heard by Israel’s ruling establishment, the Jewish Federations of North America (JFNA) held their annual General Assembly in Tel Aviv with the theme, “Israel and the Diaspora: ‘We need to talk.’ ”

In recent years, much of American Jewry’s primarily liberal communal leadership has taken vocal odds with several policies of Israel’s conservative coalition government relating to key religious issues, the protection of minorities living in Israel and an inability to reach a peace agreement with Palestinians. Many Israelis have taken odds with the progressively divisive tone of American Jewish criticisms.

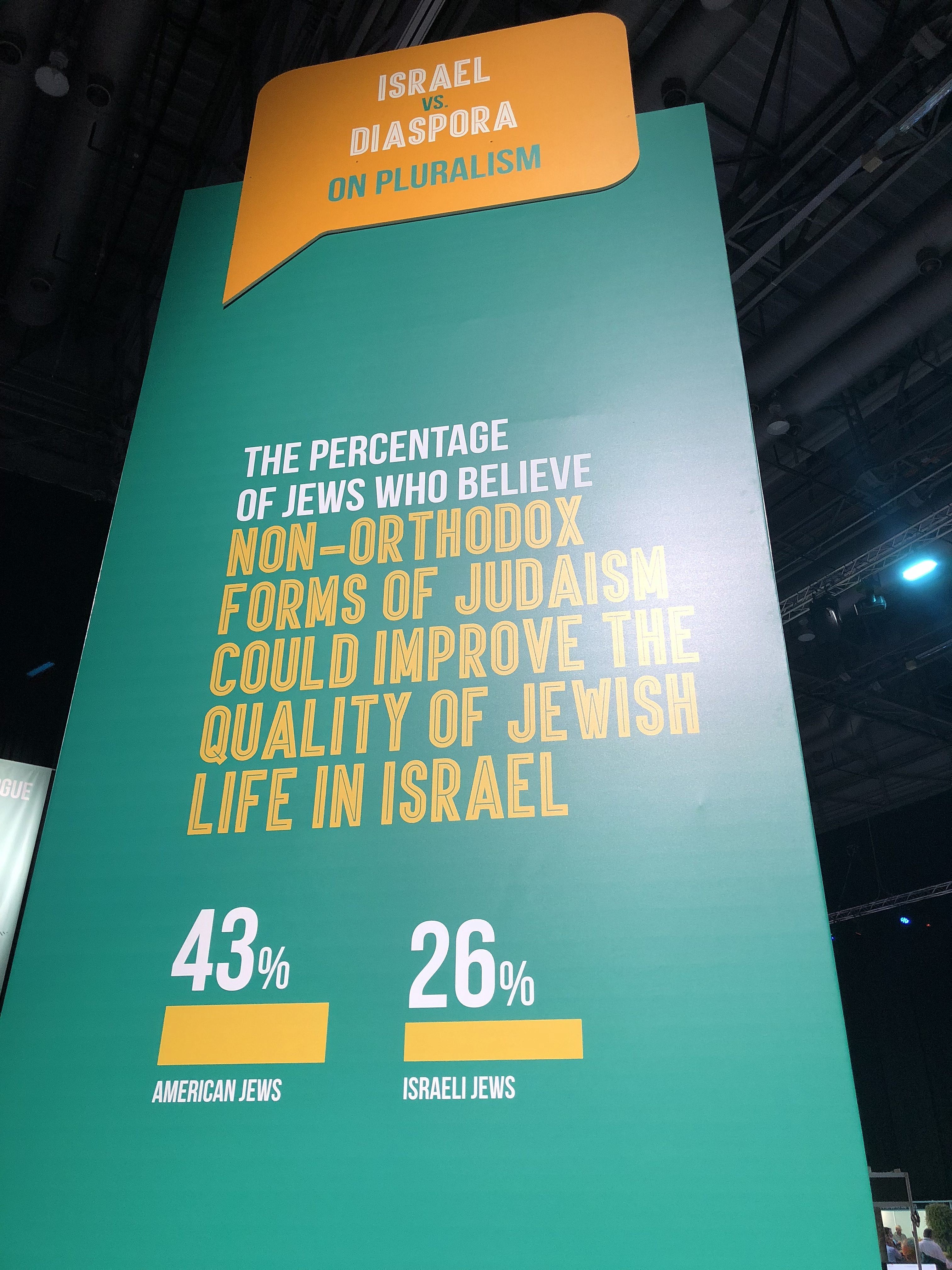

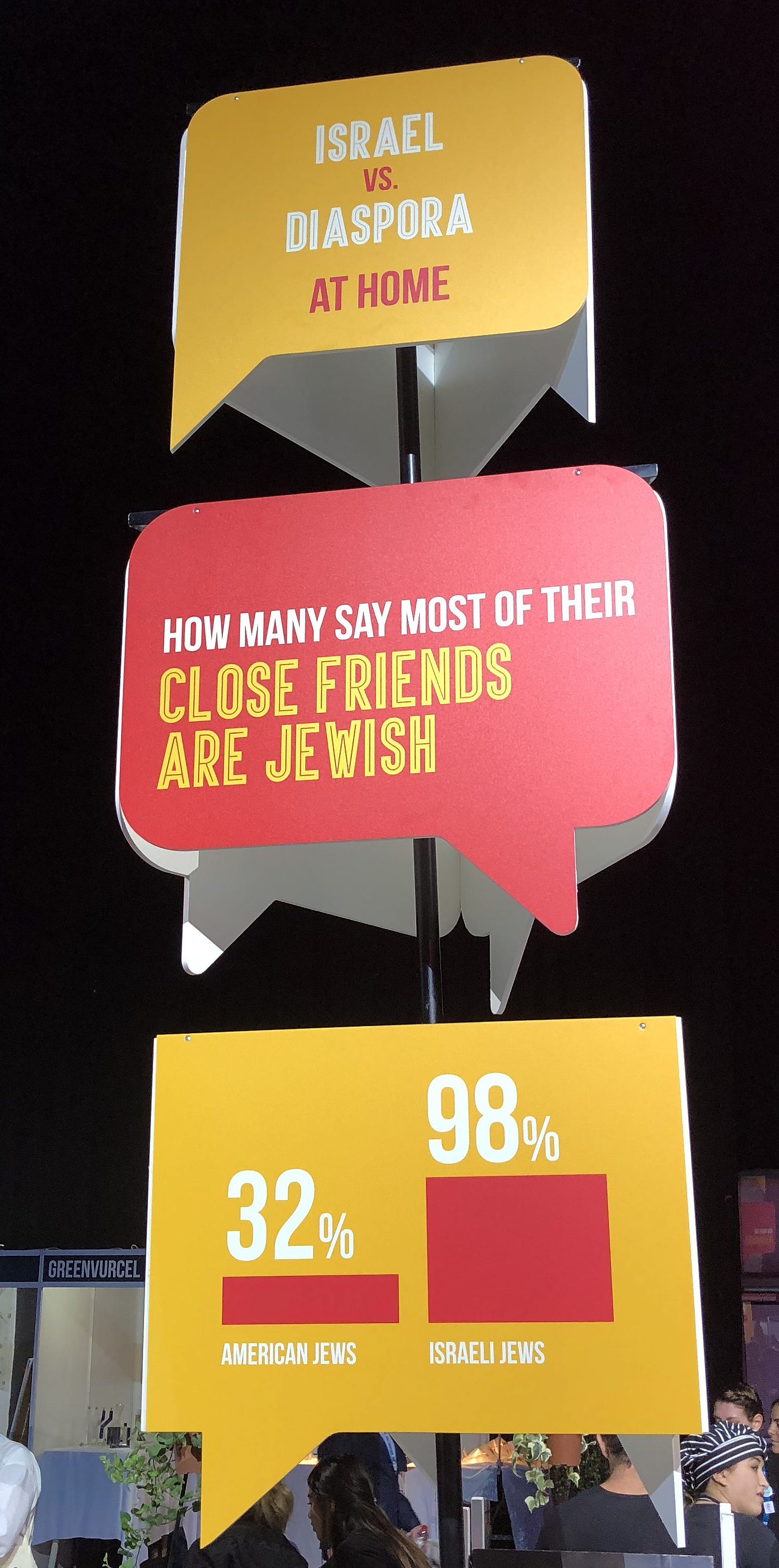

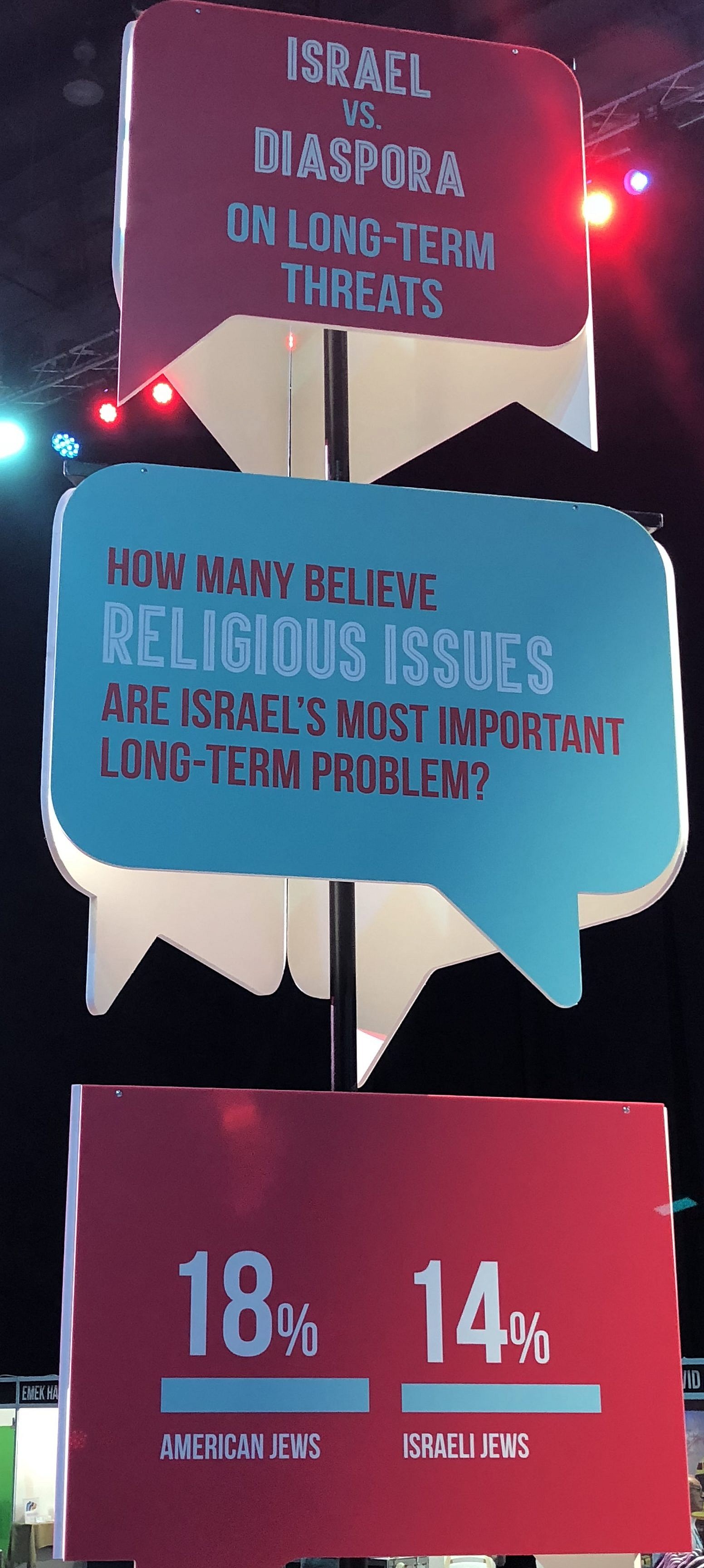

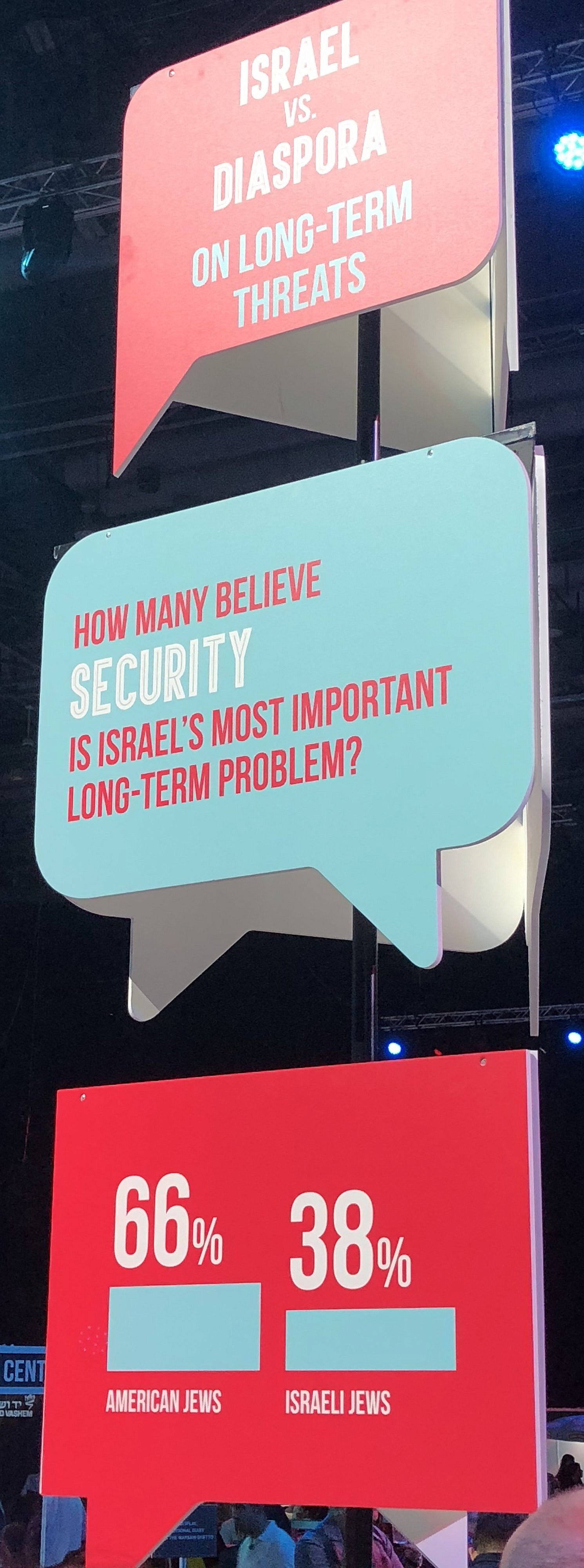

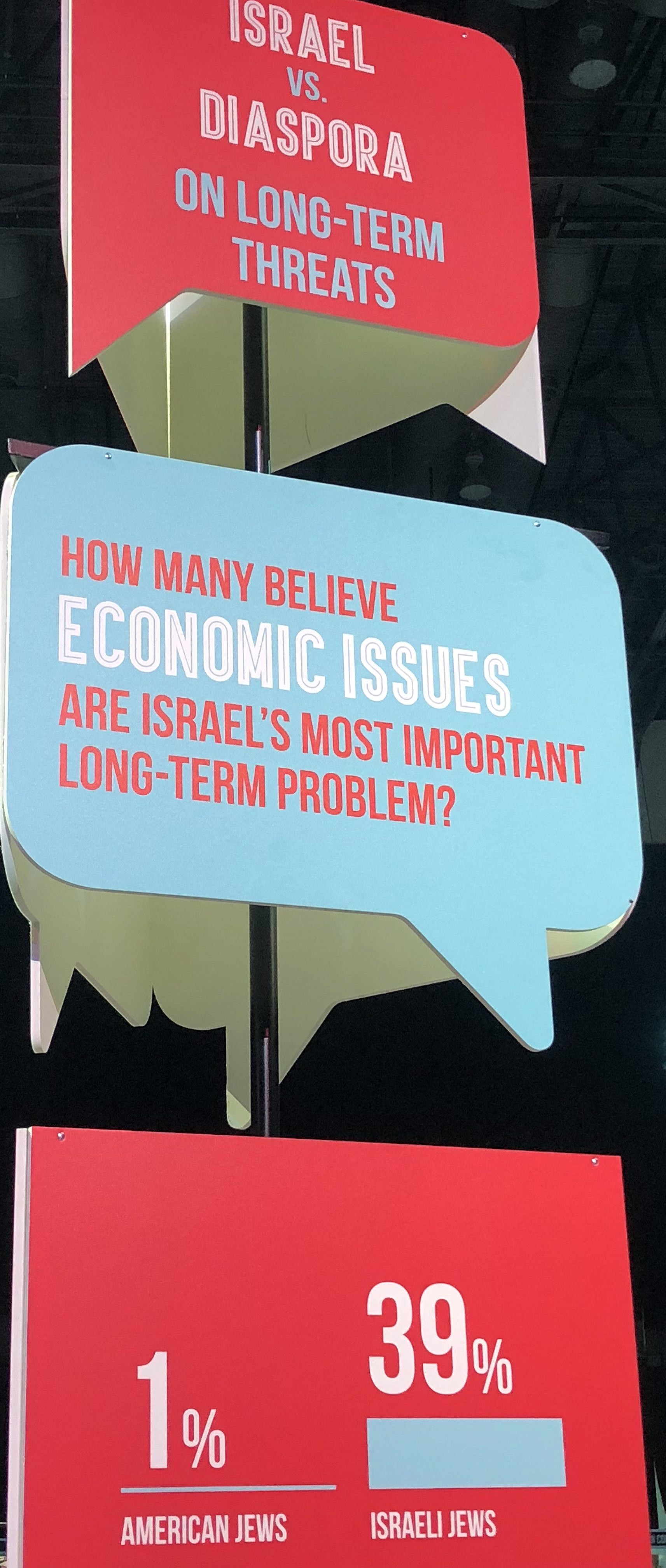

Throughout the Tel Aviv Convention Center, infographics revealed sharp differences in attitudes between American Jews and Israelis on key issues.

Israeli President Reuven Rivlin addressed the nearly 2,000 attendees of the General Assembly’s plenary, acknowledging the growing rift and need to bridge the gaps, stating, “It may not be easy to have a truly honest conversation, but this is, I believe, what needs to happen. “We cannot escape from returning to the table and re-discussing our disputes.”

Isaac Herzog, the new chairman of the Jewish Agency for Israel and former chairman of Israel’s left-wing Labor Party, seconded the need to bring the issues dividing the two poles of world Jewry.

“We must launch a new Jewish dialogue,” he said, adding that his agency, which focuses on strengthening Jewish identity and immigration to Israel, will attempt to “work together in every possible way so that Israelis will learn to appreciate and know the magnificent civilization of world Jewry, while world Jewry will learn to appreciate the achievements of Zionism and the beauty of Israeliness.”

As a major financial supporter of Israeli initiatives, America’s Jewish leadership believes that it has become an undervalued stakeholder in Israel’s development. Israelis, on the other hand, are skeptical of a Diaspora leadership that presides over a community that is rampantly assimilating and has not experienced the challenges of living in the Middle East firsthand.

While there have been a number of policy differences between the communities since Israel’s founding as a state in 1948, today these differences are seemingly highlighted over and above commonalities. In particular, recent disputes have centered around the enlargening of a little-used mixed-gender prayer section of the Western Wall plaza, Israel’s reluctance to accept less-stringent conversions to Judaism administered by Reform and Conservative clergy, and the recent passage of a controversial Nation-State Law that canonizes Israel’s existence as a Jewish state over a state of all its residents.

Speaker of the Knesset Yuli Edelstein responded accusations that by passing the Nation-State Law, Israel risks losing its democratic character. “Unfortunately, you have heard that some legislation is ruining Israeli democracy. To paraphrase Mark Twain: The rumors of the death of Israeli democracy are greatly exaggerated,” said Edelstein. “As speaker of the Knesset, I can assure you that nothing could be further from the truth. The Knesset is and will remain a beacon of democracy.”

In a lengthy question and answer session hosted by outgoing JFNA Chairman Richard Sandler, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu addressed many of the concerns, and then raised his own concern, which speaks more closely to the role of Federation leadership than to Israeli policy.

“What I am concerned with when it comes to the Jewish people is one thing, and that is the loss of identity,” said Netanyahu. “It’s not the question of the Wall or conversion, that we can overcome, it’s the loss of identity.”

‘Cognitive dissonance’ over ‘complex issues’

Eric Goldstein, CEO of UJA Federation of New York, explains that the barriers between American and Israeli Jewry are starkly different than policy differences of years’ past.

“I think that government policies over the last number of years are not always as they’ve been. They’re new, and I think it’s more in a direction that is challenging to the worldview of lots of American Jews who see their Jewishness through a lens of social justice,” Goldstein tells JNS.

“So their Jewishness is actually [constructed from] a social-justice frame, and they look at the nation-state bill, they look at settlement policy, the treatment of migrant workers … There are a lot of recent government policies that are at odds with American Jewish attitudes, primarily from the non-Orthodox world, but that said, Israel has these policies for a reason.”

On the other hand, he explained that Israel’s government “reflects the view of many of its constituents, and so Americans need to better understand why Israel thinks as it does. But Israelis, at the same time, really need to understand why American Jews believe as they do.”

Goldstein calls the differences a case of “cognitive dissonance” over “complex issues.”

Further exacerbating the rift is a polarizing political environment, particularly in the United States, where liberals and conservatives currently find little room for commonality. American Jewry historically supports Democrats near unilaterally; twice voted overwhelmingly for Barack Obama, a president who was not viewed fondly in Israel; and strongly disapproves of current U.S. President Donald Trump, who Israeli Ambassador to the United States Ron Dermer recently called “the most pro-Israel president in Israel’s history.”

The Trump presidency

Goldstein acknowledges that the political tensions of a polarized political environment in America have seeped into the Diaspora-Israel relationship. “It has to be some dimension of that, of course,” he says. “Look, you have a president who—again, non-Orthodox democratic liberal American Jews represent the majority and look at our current, our own government with a lot of unease. They see that government significantly embracing Israel’s government.

“It is almost this transitive principle that confirms some of the misgivings that many in the American Jewish community have about Israel,” he says. “So, I think that the political situation in America is certainly a part of this, but a part. These issues existed long before the current administration in America, and I think we need to recognize that they are not just short-term political challenges. We need to recognize these are challenges that have been brewing for a long time.”

Yet for all the differences between the leadership of the American Jewish community and Israel’s political establishment, strong ties remain at the root of the relationship, and both sides appeared appreciative that the Federation professional and lay leadership are coming to hold these talks in Israel.

“Personally speaking, I love coming to Israel,” says Goldstein. “It’s a core part of who we are as Jews. So on that sense, on that level, we’re never going to disconnect, and we’re always going to feel a part of Israel.”

Despite the difficulties, he sees reasons for optimism. “I clearly believe these gaps are breachable,” Goldstein told JNS.

“First of all, because they have to be. To think we are going to take the two largest centers of Jewish life and disconnect them would be an act of real tragedy because we need each other. We are a small people. We need all the power we have to be connected. So I believe we have to,” he emphasizes.

“We’re not going to all agree, but let’s find out what the common challenges are and work together to strengthen the Jewish people globally. I think that is the way forward.”