am a lifelong learner. I absolutely love updating knowledge and skills and adding a few new ones along the way. The process of going from clumsy beginner to mastery (a process which never ends) is exhilarating. However, not all learning is equal. I was miserable in school, did well when the work was interesting but could not even make myself turn in homework when it was not. It wasn’t until long after secondary school that my enthusiasm for learning reappeared, and throughout that process I had to re-learn how to learn. What works, what doesn’t, what can transform a dull subject into one that feels personal and within reach? It was the zest for learning that landed me in the middle of this classic text, above my reading level but with the knowledge that I’d be able to figure it out.

Below, I explain how I studied and analyzed a Yiddish text that once was out-of-reach through creative process, which hopefully can inspire other students to take on such seemingly impossible tasks and inspire teachers to engage their learners. Many thanks to my own teacher Mirl Tatom, who, as a musician, uses the process of creative engagement in her own classroom (her Yiddish language classes are never complete without a communal run through of a themed song or two)! Mirl inspired me to write about my own creative learning process. Throughout the text you’ll find a few of the illustrations I’ve made to accompany Itzik Manger’s Megile lider. (For information on usage and a pdf to view all the illustrations, see bottom of article)

The Process

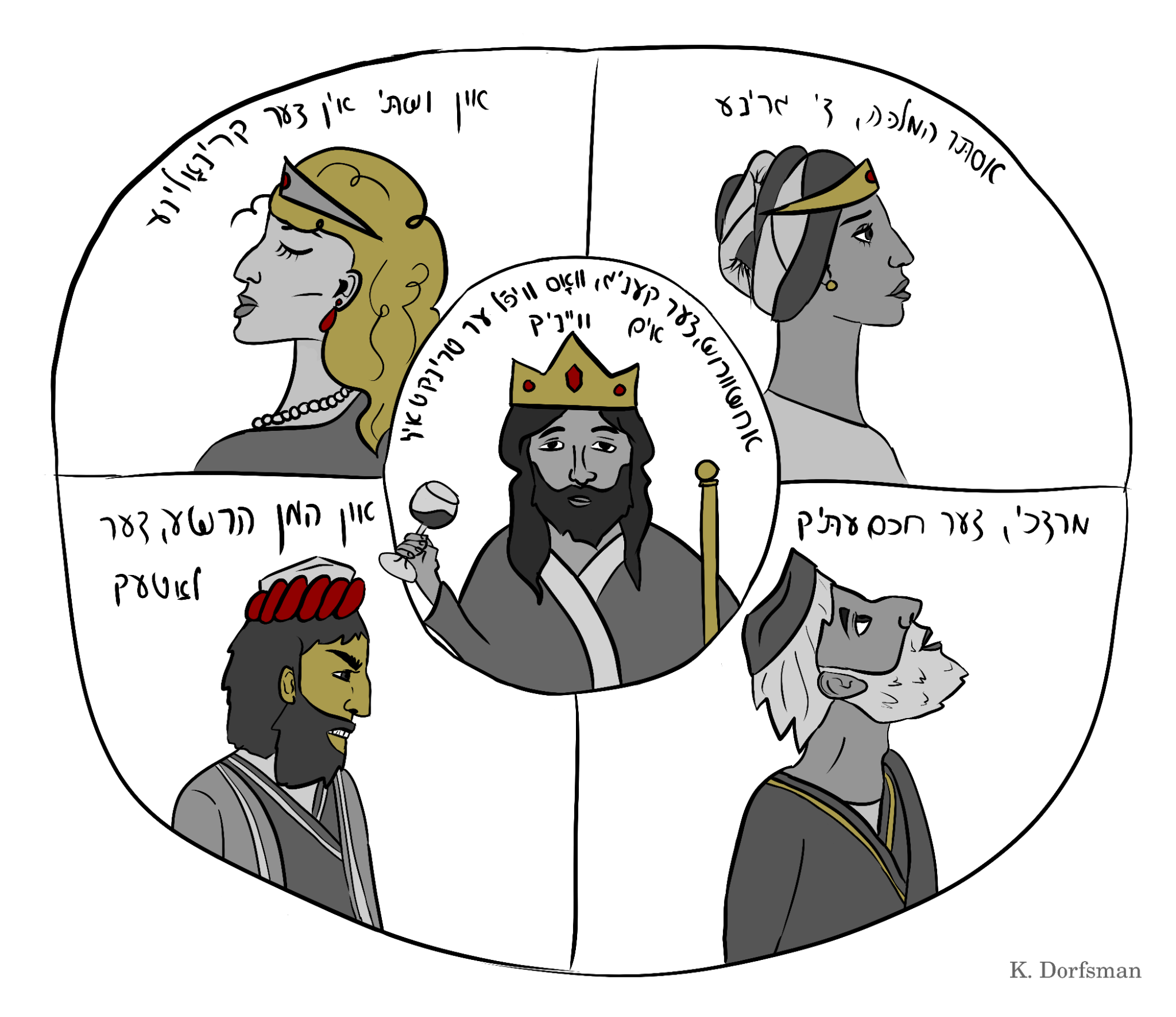

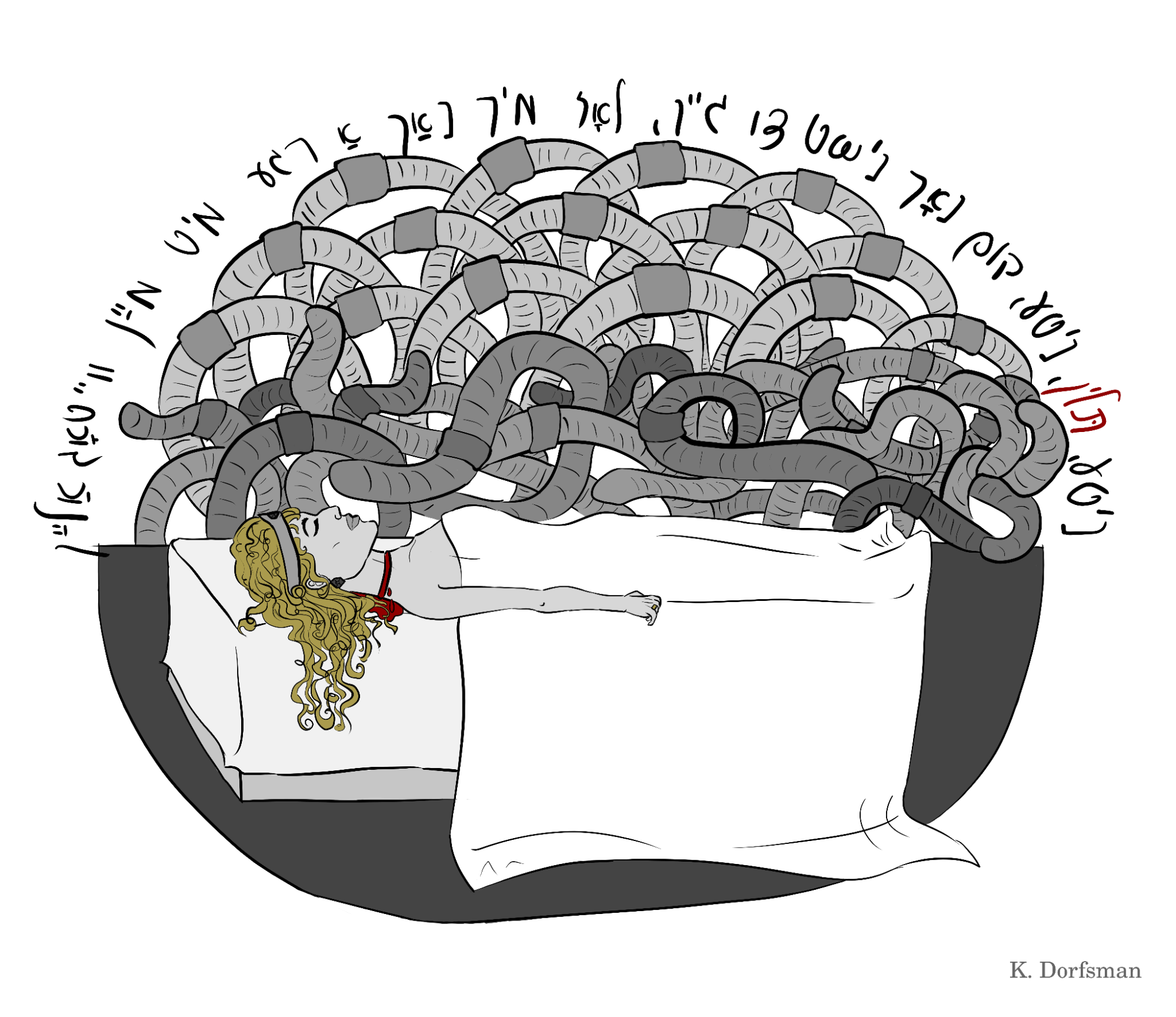

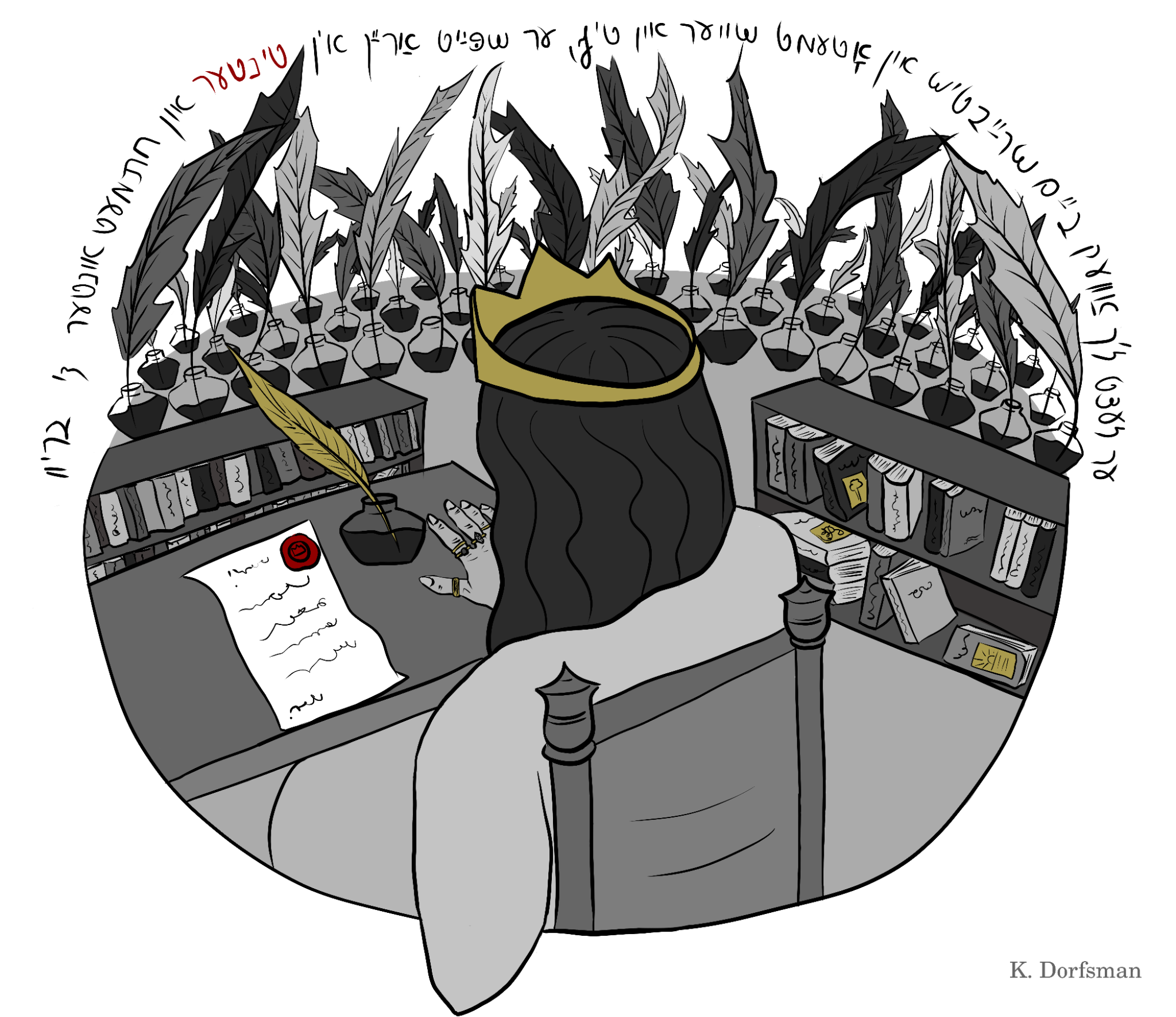

Because I am a relatively low-level Yiddish reader, Manger’s Megile lider felt out of reach forme a couple of years ago (My father jokes that Yiddish “skipped a generation” in my family; I stubbornly taught myself to read without any help until recently joining classes at the Workers’ Circle and gaining a learning community). Complex poetic language, interjections of various Slavic words and more loshn koydesh than what my peasantly vocabulary could handle abound! Despite its challenges, I was determined to get through it. However, after struggling through a single page, barely grasping the meaning and then looking down at the nearly hundred more that I’d have to get through, I was almost put off from the text. I started my regular routine of procrastinating when things get difficult. I’d just found El Lissitzky’s Had Gadya illustrations and was inspired by their style: a summary of each stanza in picture form, wrapped up in a banner of text. Because I was still trying to get a feel for Manger’s text, I started pulling together whatever I could understand of a chapter that had slightly easier language or perhaps a more predictable theme (for example, the one where Haman gets dragged off to the hangman), and illustrated it in a format similar to Lissitzky’s. I’ve been making art in some form since my childhood, although I’d never tried my hand at illustration before, thus making it a double learning project.

All of a sudden, a few of the characters had faces and expressions. I was forced to make stylistic choices about how to dress them, pay attention to the way the author treated each as individuals… I started noticing accents, vocabulary, humor! I moved on to the next chapter, not necessarily in linear order but another one I felt I could understand. The task became easier. Not only had this turned into a game with a goal — to illustrate each chapter — but it also got broken into smaller, more manageable chunks. I was also starting to build up the world in which these characters existed. It didn’t even matter whether my visuals matched with what the original author had in mind; all I needed was something to bridge the gap between our worlds, a place of familiarity to start from. It was a project that expanded and that I’d come back to over time, but after completing it, I did eventually have the courage and understanding to read through the text in its entirety, in linear order. I can hold a coherent conversation about the text and even analyze stylistic details with people much more fluent than I thanks to the depth that art brought to my reading.

The Analysis

From our earliest moments, we are taught to learn in song. Almost every secular as well as religious sphere has utilized music as a primary tool in oral memorization – from the melody of the alphabet song, prompting us to find the next letter on our tongues, to using trope to preserve an entire oral work down to the individual syllable. The value of involving one’s creative process in learning has certainly passed the test of time.

Starting around the fifteenth century (and even before that to a lesser extent), print slowly became the easier way to distribute, translate, and preserve ideas . But we should ask ourselves if we’ve really fully adapted to print in the sphere of learning. Since we don’t often use rote memorization to learn orally, is a linear reading of texts the best way to learn in the printed format? We do offer illustrated tales to children, which would be the equivalent of them listening to a song (rather than singing it themselves), but their brains may not be as fully engaged as if they were creating artwork to accompany the reading, or even coloring in some lines in a way that forced engagement with the text (paying attention to details about color that may appear in the text for example). Not only does creating illustrations make attention to detail inevitable, but it also personalizes the text to each individual; the learner weaves a piece of themselves into the material and is more likely to remember what was read. As stated above, another useful consequence of this learning style is the fact that it makes us break the text down into smaller pieces that can be summarized by the art, rather than dealing with the intimidation of staring down hundreds of pages when a single one has already proven itself difficult.

But why use visual art rather than other creative outlets when learning a text? Every creative medium (writing, drawing, singing, even discussion in groups) is valuable, depending on the individual learner, the text and the learning space. The reason I have chosen to focus on graphic art lies in its communicative value. Walter Benjamin’s thoughts on translation and language as well as my affinity for art guide me towards viewing everything around me as having communicative potential. In Benjamin’s On Language as such and on the Language of Man, we read “…it is certain that the language of art can be understood only in the deepest relationship to the doctrine of signs… For language is in every case not only communication of the communicable but also, at the same time, a symbol of the noncommunicable.”11 Benjamin sees art as a portal to the world of semiotics (“sign” is language as means, a representation of the original). What Benjamin means in the second part of the quote is that whatever is said in language reveals in the same instance what cannot possibly be communicated. My own continuation of this train of thought leads me to see the symbolic as something which can preserve the unsayable without decoding it, and transmit both parts without distortion.

From theory to application: Visual art can be used to translate pieces of the text into a new medium. It’s the responsibility of the art-translator to convey the message without over-explaining the symbolic elements. Or rather, to convey the symbolism in the writing as symbol itself, while still communicating semantic elements efficiently. Communicative language lies in the fragile boundaries between signification and pure language (language which only communicates itself); figuring out where elements of each are appropriate is the space in which learning and transmitting are possible.

Knowing this, it’s hard to use a written or even oral method to come to an understanding using language. We run the risk of further obscuring the meaning of what we already don’t understand. Art has as an advantage the ability to convey all communicative elements without reducing the text. In less abstract terms, anything that is explicitly written can be painted as such. The author describes a character as being blonde, and we can choose a blonde color to paint the picture accurately. The more subtle, symbolic elements can be implied as fine, elegant lines, or rather thick strong lines. Bold colors or no color. Sharp and soft edges. Facial expressions that can mean so much or so little depending on the viewer. This means that the symbolic elements are not reduced to explanatory text which may not follow the author’s intentions anyhow, but rather transferred from symbolic text to visual symbols, sometimes updated to a new audience. (The original semiotes are liable to being lost to time, so this method allows preservation of semiotic elements so that each generation can impart its own meaning from it). This also allows us to view the work anew each time we come back to it (not only changing through time but also through experiences) and continue delving into its deep pool of meaning, as our interpretation of the symbolic will never be the same twice and our art will not allow us to pin it in place as much as writing might.

Conclusion

What initially may appear childish and trivial at first, as concerns creative learning tools, can now hopefully be seen as a worthy pursuit. Not only is the technique well suited to interpretation of text, but as an active learning process, its potential to engage learners is unrivalled.

Click here to download a PDF with all of Klervi Dorfman’s illustrations and references to page numbers in Manger’s Megile Lider. Please note the fair use license below.

Fair use: The visual materials in this article and in the document above may be used as teaching aids. They may not be used in a commercial manner and the author’s signature may not be removed.