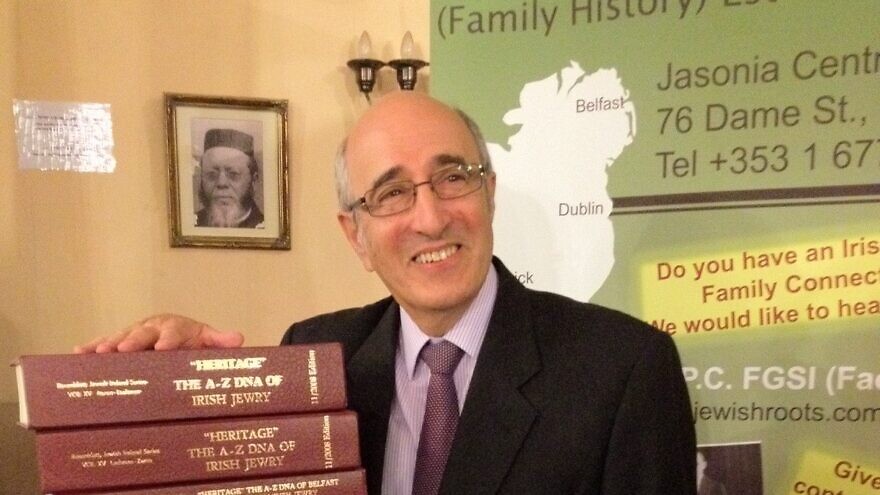

Genealogist Stuart Rosenblatt on Dec. 19 will donate his treasure trove of records on Irish-Jewish families, which spans centuries, to the National Library of Israel in Jerusalem. For decades, he has been the go-to source for everyone with Irish Jewish ancestry seeking to learn about their lineage.

Rosenblatt is currently head of the Irish Jewish Genealogical Society, formed in 1999 as a division of the Irish Jewish Museum, and president of the Genealogical Society of Ireland.

Over time, recording his own family tree branched off, and he uncovered information on the entire Irish-Jewish community. The records span over 70,000 individual names. Many lineages go back 300 years but the oldest stretch as far back as 1555 (when most Irish Jews were of Spanish-Sephardic heritage). But today, most of their ancestry hails from Eastern European Ashkenazi Jews from Lithuania and neighboring nations who arrived in the 1870s.

Common folktales hold that unscrupulous captains told them they had reached the U.S., so they could resell their tickets; not knowing the English language they would disembark in “Cork” thinking it was “New York.” One particular individual was in Limerick for two weeks before he realized that he was not in the U.S. Others say that the ships ran out of kosher options so the starving Jews got off — but whatever grain of truth there is to these fables, they became an integral part of Irish history.

The Irish-Jewish community peaked at 5,000 people in the 1950s; afterwards many emigrated to Israel, the U.K. and the US. Smaller numbers live in Australia, Canada and even one individual in Vietnam. In the Republic of Ireland, there are now 500 registered Jews in two congregations in the Republic of Ireland and one in Belfast. Many synagogues have shut down in the last few decades. As the community dispersed and the elderly who remember their heyday in Ireland passed away, this research gained increased importance.

Anne Lapedus Brest, who left Ireland over 60 years ago as a teenager and now resides in South Africa, says, “Stuart is a brilliant man, and he deserves a knighthood. I visit Ireland every year, and when I pass by a house, I may remember it as ‘Mr. Cohen’s House,’ but Mr. Cohen doesn’t live there anymore. I sometimes want to walk down memory lane, but Dublin has changed so much. They’re all gone—most of the Jews have left. But Stuart is a living encyclopedia who can tell you about them. He didn’t pick this information out of thin air; he did the hard work with much dedication and has done a great service to the Jewish community.”

Rosenblatt’s work was very meticulous. As he would interview people, he visited all 32 counties in the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland (part of the U.K.). He looked for school records (which many were delighted to show him, while the Jewish school outright refused). Schools had records of pupils’ religious affiliations. He visited graves in Limerick, Cork, Dublin, and Belfast for clues, checked marriage records, and didn’t leave a single stone unturned—not just metaphorically.

“Circumcision records are rare, although in one record, Reverend Abraham Gittleson, in an entry under ‘Observations’ noted that the nurse fainted! And that stood out!” Rosenblatt says with a smile.

Rosenblatt, through oral testimonies recently uncovered evidence which revealed that Michael Collins, a renowned Irish independence hero hid among the Irish Jews, posing as an elderly Orthodox man to evade capture by the British authorities in 1920.

Maerton Davis, who moved to Israel from Dublin in the 1970s, said “I think it was 20 or 30 years ago, I met up with Stuart when he first began doing this. He asked to meet up for ‘a wee bit,’ but we ended up spending eight hours together tracing one side of the family; this was before we had the internet and smartphones mind you. It’s an amazing feat because back then he wasn’t retired yet; he had his own business, and he was still doing this. And nobody funded him! Even now he is constantly updating the records on the computer.”

Rosenblatt added, “And I still haven’t found out where my grandmother is buried in Poland, but I would love to go there and say kaddish (a mourning prayer ritual) if I could find her grave. I also have no idea where my relatives on her side are now.”

So while he was able to do extensive research for the community at large, Rosenblatt’s own family tree still eludes him.

Five copies of this work exist; four are in Ireland. The fifth set, Rosenblatt’s personal copies, have in his words “come home to Jerusalem” and will be housed in the Irish Section’s “Rosenblatt collection.”

A presentation ceremony of these volumes will take place at the National Library of Israel in Jerusalem on Monday, Dec. 19.

Rosenblatt may be contacted on srosenblatt@irishjewishroots.com or +447889794757, for anyone of Irish-Jewish lineage who wishes to receive an outline of their family tree.