Manouchehr Bibiyan, a pioneering Iranian-American Jewish entertainment producer and political activist died on Aug. 27 in Los Angeles. He was 90 years old.

Bibiyan became Iran’s first and most successful modern pop-music recording producer, having released some 6,000 songs in Iran during the 1960s and 1970s through his various music labels.

If anyone wanted to listen to pop music in Iran before the early 1960s, it was either go to a nightclub or listen to what the national government radio station happened to be playing, Bijan Khalili, an Iranian-American Jewish publisher and longtime friend of Bibiyan’s in Los Angeles, told JNS.

“That all changed with Manouchehr Bibiyan, a true visionary businessman, who decided to record Iran’s pop music on records that could be bought and listened to by millions across Iran whenever they wished,” he said.

Secured a weekly program on television

Born to a Jewish family in Tehran in 1933, Bibiyan experienced antisemitism from a young age. He often came home from school with torn clothes or with cuts after being beaten by Muslim kids in his neighborhood, his family members told JNS.

When he was 14, his parents couldn’t stop him from joining an Iraqi family that had come to Iran en route to immigrating to Israel, his widow, Mona Bibiyan, told JNS.

“It was around the time of Israel’s independence, and he served in the Israeli army, lived on a kibbutz and went to university there,” she said.

Bibiyan’s family members told JNS that by age 20, he returned to Iran because he missed his family and sought better financial opportunities.

“He had been exposed to Western music while living in Israel, and when he returned to Iran, he borrowed money from his father and opened a record store by the name of Apollon, selling European and American music records,” said Kourosh Bibiyan, his oldest of three sons.

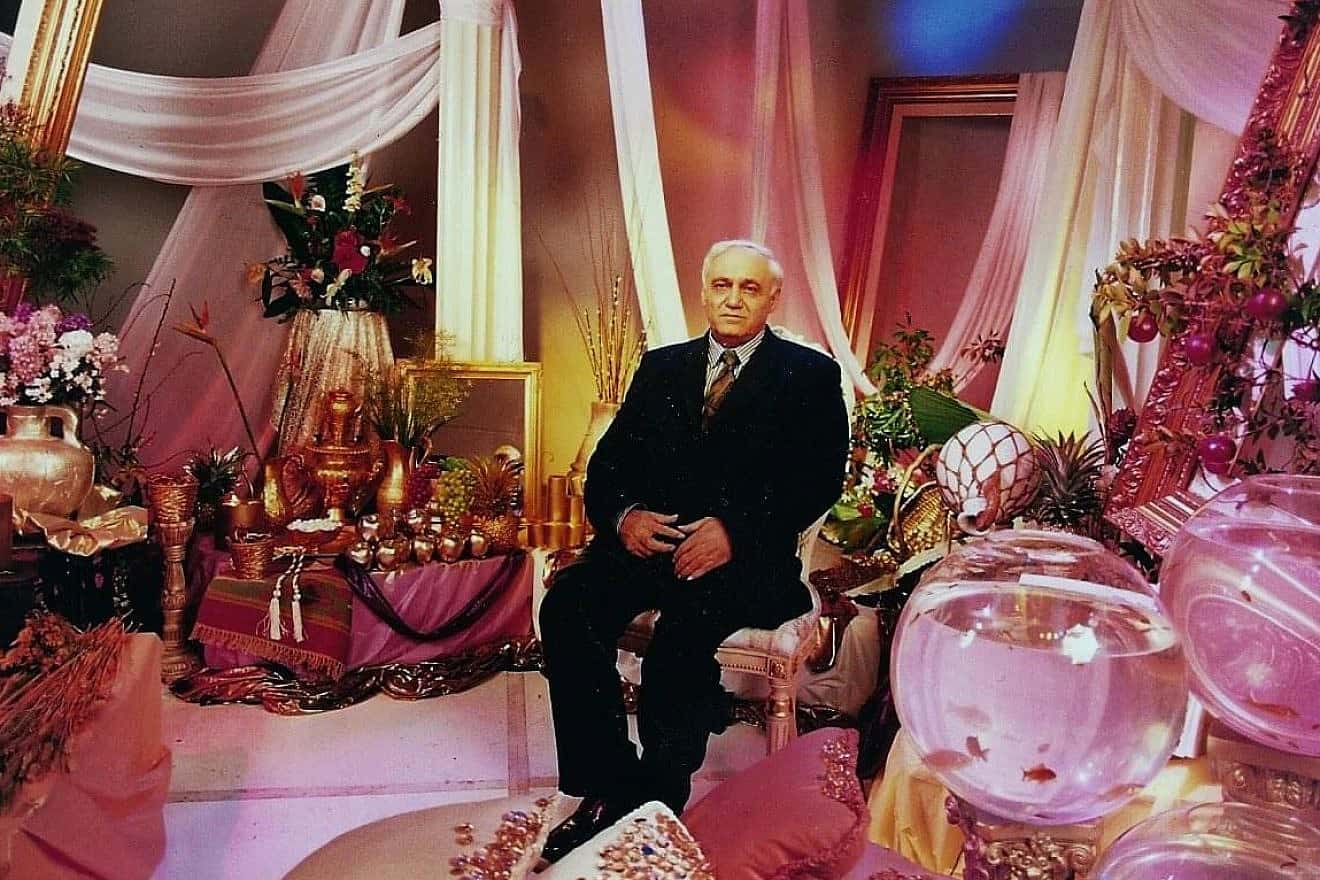

Between 1959 and 1960, Bibiyan secured a weekly program on Iran’s national television network called “Tea for Two,” which featured photo slides and music. It was entirely sponsored by Bibiyan’s Apollon record store, Kourosh told JNS.

Bibiyan noted the lack of contemporary Iranian pop music available publicly at the time, so in 1965, he became the first Iranian to record pop musicians and singers. He did so on the Apollon label and on other private labels of his. The records were pressed in Europe and shipped to Iran for distribution.

“Between 1965 and 1979, my father was responsible for releasing some 6,000 songs from many different pop-music singers in Iran—stars like Dariush, Googoosh, Sattar, Hayedeh, Vigen and Mahasti became famous because of Bibiyan,” Kourosh said.

That sextet of singers in Iran might be comparable to Frank Sinatra, Diana Ross, Madonna and Aretha Franklin in the United States.

“The songs of that era were more meaningful, and he himself chose the lyrics,

the music and even decided which singer would sing each specific song,” Kourosh said.

Intellectual property

By 1969, Bibiyan produced and manufactured Iranian pop-music records in Iran, expanding the nation’s exposure to that music with sales of new cassette technology, which was introduced in Iran in the 1970s.

He was also responsible for importing and selling record players and cassette players for cars in Iran so that millions of Iranians were able to listen to their favorite music whenever they wanted, Kourosh said.

Khalili, Bibiyan’s friend, said the latter also pushed the passage of copyright laws, which the Iranian legislature did in the 1960s to protect the intellectual property of songwriters and artists.

“The concept of copyright protection was foreign in Iran during that time, and the copyright laws Manochehr Bibiyan helped create allowed contemporary musicians, singers and artists to flourish by getting paid for their craft,” Khalili said.

“Because of these new laws in Iran, he was able to pay royalties to artists for the first time ever in the country,” he added. “This encouraged more music to be created.”

Family members noted that Bibiyan’s success building Iran’s recording industry also put him in the crosshairs of Muslim extremists in Iran, where he faced significant antisemitism and accusations of disloyalty.

“In the years before the Islamic revolution in Iran, many Islamists in Iran who were jealous of him began spreading false rumors that Bibiyan was making all of this money and buying F-4 Phantom aircraft for the Israelis,” Kourosh told JNS.

“These were all lies,” he said of his father. “He was a proud Jew. He loved Israel, but he was also a very patriotic Iranian.”

Living in exile in America

Bibiyan and his family were forced to flee Iran after the 1979 Islamic Revolution. They eventually resettled in Los Angeles, where he picked up professionally where he had left off. He created Pars Video, a company that released Persian entertainment programs on video cassettes for Iranians in Southern California, Kourosh said.

Bibiyan left Pars Video to his brother in 1981 and on a shoestring budget started the one-hour, Persian language “Jaam-e-Jam” television program on Los Angeles’ KSCI, Channel 18. The weekly program provided commentary on political events in Iran and entertainment to Iranians in Southern California.

At first, “Jaam-e-Jam” operated out of the family’s two-bedroom Los Angeles apartment, Kourosh told JNS. Money was tight.

“There weren’t any Iranian businesses set up that could buy advertising time from us, and it wasn’t easy,” he said. “In the beginning, I was the cameraman, the mic operator, the editor and handled everything else technical on the show.”

The program took a lot of risks by criticizing then-Iran Supreme Leader Ruhollah Khomeini at a time when many ex-pat Iranians living abroad feared reprisals from the regime, Pooya Dayanim, an Iranian Jewish attorney in Los Angeles and friend of Bibiyan, told JNS.

Bibiyan’s work became even more profound in his California exile, according to Dayanim.

“He now regarded himself as a guardian of Iranian culture, history and music, and became political,” he said. “He was the producer who stood by the immortal Rafi Khachatourian,” when the Iranian comedian “was the only one who was engaged in political satire against Ayatollah Khomeini.”

‘Historic interviews’

On “Jaam-e-Jam,” Bibiyan interviewed prominent U.S., European and Iranian officials—the latter from the regime of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the late shah—to better understand the development of the revolution. That included on-camera interviews with Henry and Kissinger and Alexander Haig, both former U.S. secretaries of state; as well as Shapour Bakhtiar, former Iranian prime minister.

“They provided firsthand information about how the 1979 Islamic Revolution successfully brought about the downfall of the shah,” Khalili told JNS. “In recent years, we transcribed those historic video interviews and published them in a Farsi-language book called The Secrets of the Iranian Revolution.”

The latter has been “a unique resource for those in academia to use in their research of the revolution,” Khalili claimed.

Yar Meshkaty was one of many non-Jewish Iranian-American activists in California who opposed Iran’s Islamic regime and appreciated Bibiyan’s support of their efforts in the early 1980s.

“I was part of a college student group here in L.A. named Gamma that was actively opposed to the mullah regime in Iran,” Meshkaty told JNS. Bibiyan “was instrumental in giving us a voice and exposing the crimes of the Islamic regime on his television program,” he added.

Sassan Kamali, a former “Jaam-e-Jam” host and Iranian media personality (who lives in LA and is not Jewish), credited Bibiyan with bringing together Iranian expats of different faiths and ages in “a sense of brotherhood.”

“He was indeed a special man, who was a unifier of Jews and Muslims in the community, as well as the younger generation and older generation of Iranians with his television programming,” Kamali said.

In 2013, Bibiyan shut down “Jaam-e-Jam.” It couldn’t compete on a global scale with the BBC’s Persian network and other much wealthier 24-hour Persian networks. Soon thereafter, he retired.

His legacy will be that of preserving Iranian music and arts for Jewish and non-Jewish Iranian expats alike, admirers say.

“By supporting actors, singers, musicians—although with the meager funds that were available to him—he helped keep Iranian culture alive in exile and kept exiled Iranians in love with their country Iran,” Dayanim said.

In addition to his wife and three sons, Bibiyan is survived by his daughter and two grandchildren.