The nine young Iraqi Jewish men hanging in the center of Liberation Square in Baghdad in January 1969 after being accused by the Ba’athist regime of espionage were the subject of great interest that day, as hundreds of thousands of Iraqis came to view their corpses—not only causing a terrific traffic jam in Baghdad, but also sowing deep fear throughout the millennia-old Jewish community there. Seven months later, three more Jews were executed.

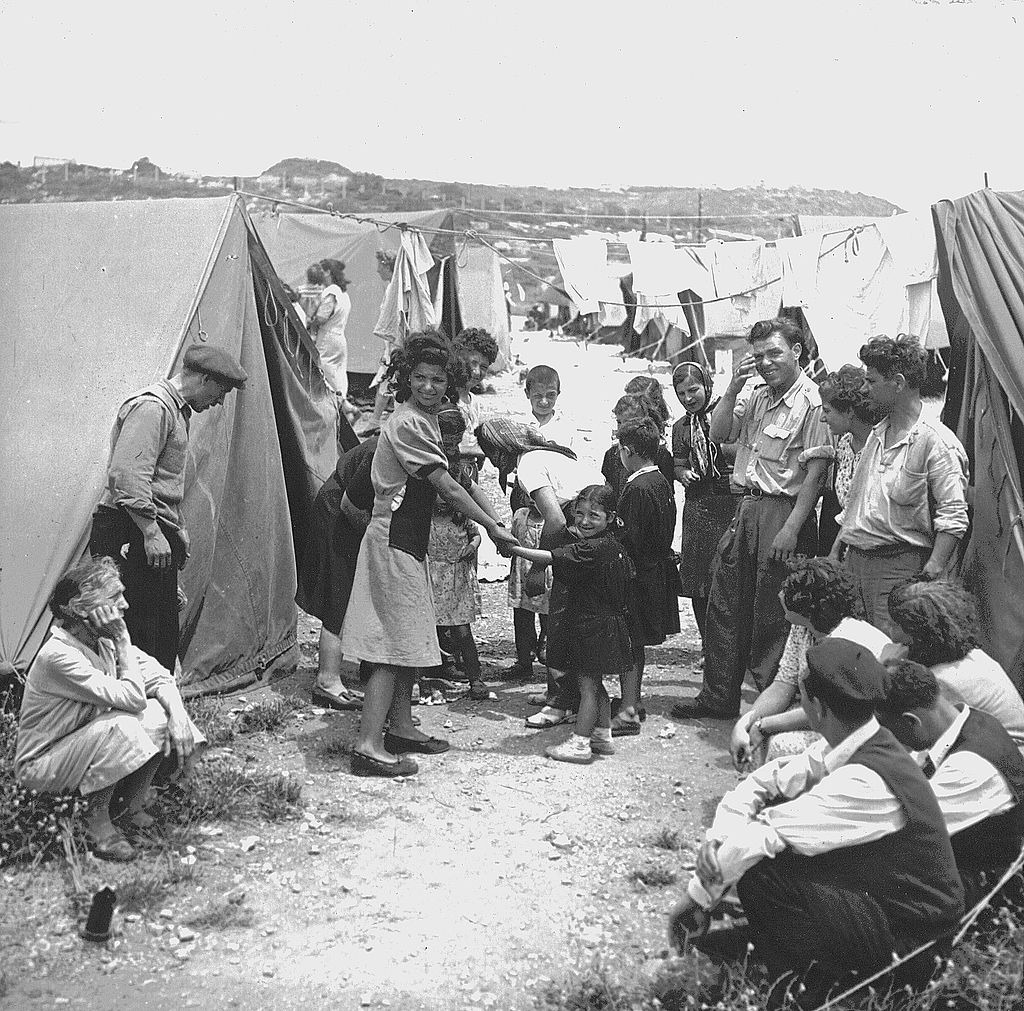

The horrific episode was part of the history of the estimated 900,000 Jews born in Iran and the Arab world who were forced to flee their ancient homes during the mid-20th century.

Few Jews remain in Arab countries and Iran; nevertheless, a new effort is underway to set a global day of commemoration to remember the Jewish communities throughout the Middle East, in addition to the graves that cannot be visited by family and for whom no one recites Kaddish, the Jewish prayer for mourning the dead.

“There is a common story among the Jews throughout the Middle East that has been forgotten, not mentioned and silent for the last half-century, and we feel—as people who came from there—that this is a story that is a vital part of Israel, the whole Middle East and of Jewish history,” David Dangoor, a businessman, philanthropist and vice president of the World Organization of Jews from Iraq, told JNS.

Today, based on this effort, a new initiative is being spearheaded by Dangoor with the goal to recruit synagogues around the world to say a special prayer on the Shabbat closest to that date.

We have now “an opportunity to raise awareness” on this topic “and to pay our respects to all those of our ancestors who are buried there whose graves are in disrepair and which we cannot visit. … It is intended to be recited around the world and to create a sense of community.”

On Nov. 29, 1947, the U.N. General Assembly adopted Resolution 181 recommending a partition of British Mandate Palestine, and called for a Jewish state and an Arab state, which the Jews accepted and the Arabs rejected. Immediately after the vote, the Arab countries turned on their Jewish populations, confiscating their businesses and stripping them of their rights, much like the Nuremberg laws of 1935. Many Jews were persecuted and murdered, and thousands were forced to flee their homes. For this reason, the next day, Nov. 30, was chosen as a day to remember.

“There is that linkage,” said Dangoor. “It is a date around which a lot of commemoration can coalesce.”

This past weekend, more than 50 synagogues in the United States and Canada, as well as in the United Kingdom, France and Israel, all recited the prayer composed by Rabbi Joseph Dweck, senior rabbi of the Spanish-Portuguese community in London, in commemoration of the people who were persecuted, exiled or killed for being Jewish. Last year, only 12 synagogues participated in the effort; the initiative is clearly gaining traction.

Part of the text reads: “We have seen with pained hearts the murder of our brothers and sisters and the burning of our synagogues and our Torah scrolls by the hands of our Arab neighbours amongst whom we have dwelt for generations. … Lord full of mercy … give rest on the wings of the Divine Presence … to the souls of our brothers and sisters who died and who were murdered by the hands of cruel enemies in the Arab Lands. Our dwelling places became fiery furnaces and our friends turned to foes.”

Acknowledging that the commemoration’s true intent is still unclear, noted Dangoor, “we need to feel our way. Is it the expulsion? Is it the murders of so many Jews? Or is it the loss of heritage?”

In part, he said, “it is a political statement to say, ‘We were here and we were expelled and we want the world at least not to forget that.’ Some of it is a genuine desire to commemorate one’s ancestors and the martyrs who were killed along the way.”

‘These are our ancestors’

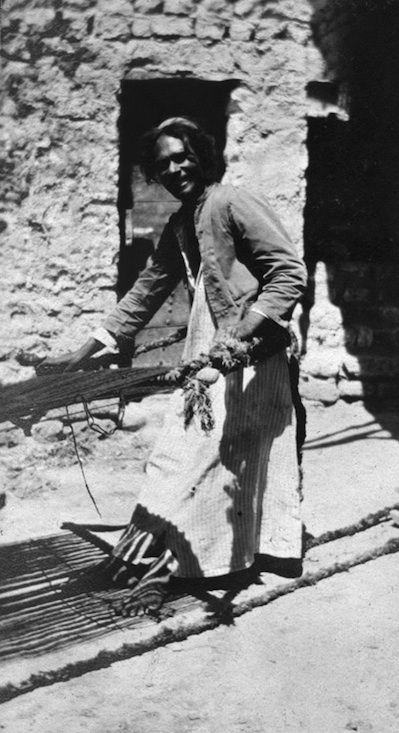

In addition to the aspect of remembering those Jews whose stories have been forgotten, this effort simultaneously exposes the history of the Jews who lived in these lands long before the advent of Islam.

When Nebuchadnezzar captured Jerusalem and destroyed the First Temple in 586 BCE, he exiled many Jews to Babylon, what is today known as Iraq. Thus, Jews called Baghdad their home for more than 2,500 years.

A good portion of Israelis link their backgrounds and traditions to the Middle East, North Africa and Arab countries. “This is also an opportunity for us to make the point that we are the indigenous people, and the story of sitting and weeping by the rivers of Babylon is not of some long extinct tribe. These are our own ancestors,” affirmed Dangoor.

There was a time when the Iraqi Jewish community was the epicenter of Jewish life, and Jews were valued and respected and considered by their Muslim brethren as Arabs. In fact, Dangoor’s own mother was crowned as the first-ever “Miss Iraq.”

Dangoor commissioned the internationally acclaimed film “Remember Baghdad,” which tells the story of Jews who fled Iraq. The Iraqi embassy sent a delegation to the screening and expressed their desire to re-establish relations with the Jews of Iraq and their descendants.

‘Iraq needs to change its stance’

Israel is, of course, a major sticking point in any potential rapprochement between Iraq and its Jews.

According to Dangoor, “a lot of the clerics—the Shi’ites and the ones who have allegiance to Iran—are much more zealous in not wanting to have any connection with Israel, whereas others now see Israel as a very positive potential force in the Middle East, but they can’t come out openly and say that. They do see the Jews as a bridge.”

Surprisingly perhaps, “many Iraqis openly play recordings of Israeli singer Dudu Tassa,” said Dangoor. “So, culturally, Israel is not viewed as ‘bad,’ but for some—mainly those linked to fundamentalists and to Iran—they stop at anything that smacks of recognition of Israel. So it is a nuanced situation.”

Will Iraq now open its doors to Jews?

According to Dangoor, Iraq finds the former Jewish community to be “a good vehicle to make this rapprochement without appearing to recognize Israel.”

“They realize how important the Jews were in Iraq,” he added. “Really, Iraq needs to change its stance and show that it absolutely, positively values and cherishes the Jewish part of its history.”

Affirming the prominent Jewish presence there, a 1917 British intelligence document records that the Jews of Baghdad once comprised 40 percent of the population. Interestingly, the report insists on the validity of the numbers “in anticipation of racial claims which are sure to be made sooner or later.”

Two years ago, a delegation of heads of Iraqi cultural organizations asked to meet with heads of the Jewish community of Iraq in London. They were impressed by how much success Iraqi Jews have had in the United Kingdom and asked why they can’t replicate their success in Iraq.

“We said we would love to,” recalled Dangoor. However, he also told them that the Iraqi government “must make it clear that the current equivocal position on the Jews sometimes seen as part and parcel of Iraqi heritage—and at other times no more than representatives of an enemy state—must change. That needs to be brought up to date and normalized.”

Asked why the initiative is only now getting off the ground, Dangoor said “it is a question mark as to why it hasn’t occurred, but it is starting to occur, and it is going to occur in a gradual and cumulative way. It’s a process of accretion. Every little bit will build a structure that is no doubt overdue.”