The foundation of the Republic of Latvia in November 1918 went hand in hand with significant changes for the Jewish population: From then on, Jewish citizens had equal rights as well as the opportunity to become politically active and set up and manage their own cultural institutions. A small minority of the Jewish population was thoroughly assimilated to German culture and occasionally referred to themselves as “Germans of Jewish faith.” Very little is known about the milieu of this group that experienced a cultural renaissance in Latvia as a result of the tolerant legislative attitude towards minorities in the time between the world wars. A new research project at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (JGU) intends to address this topic and explore the lifestyle of German-acculturated Jews and their cultural interactions with Germans in the period in question. The project “Jews and Germans in Latvia 1919-1939: Routes of acculturation, Identity, Reception” is being sponsored by the Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and the Media, Monika Grütters. Funding is being provided as part of the program on German-Jewish Lifeworlds in Eastern Europe and will amount to EUR 80,000 over the next four years.

The foundation of the Republic of Latvia in November 1918 went hand in hand with significant changes for the Jewish population: From then on, Jewish citizens had equal rights as well as the opportunity to become politically active and set up and manage their own cultural institutions. A small minority of the Jewish population was thoroughly assimilated to German culture and occasionally referred to themselves as “Germans of Jewish faith.” Very little is known about the milieu of this group that experienced a cultural renaissance in Latvia as a result of the tolerant legislative attitude towards minorities in the time between the world wars. A new research project at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (JGU) intends to address this topic and explore the lifestyle of German-acculturated Jews and their cultural interactions with Germans in the period in question. The project “Jews and Germans in Latvia 1919-1939: Routes of acculturation, Identity, Reception” is being sponsored by the Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and the Media, Monika Grütters. Funding is being provided as part of the program on German-Jewish Lifeworlds in Eastern Europe and will amount to EUR 80,000 over the next four years.

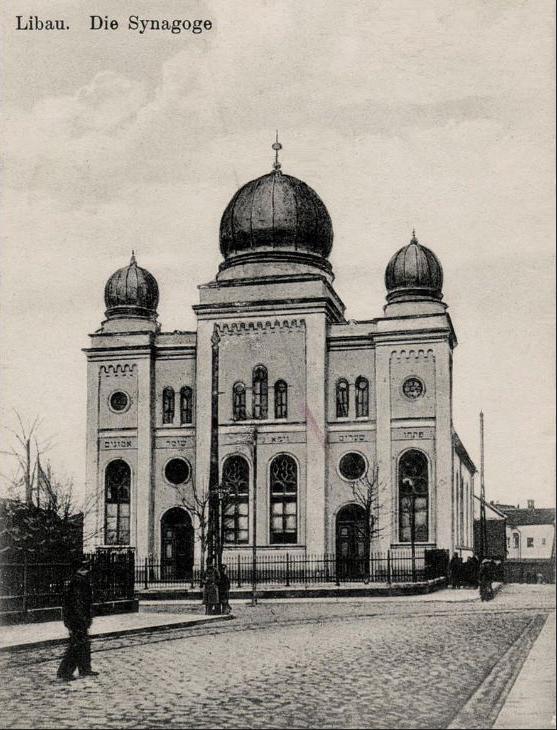

In 1918, Jewish society in Latvia was diverse in terms of both its religious and cultural manifestations. Yiddish-speaking Jews who had migrated from Riga and Kurland during the second half of the 19th century formed the largest group. A smaller group of educated Jews had adopted a Russian cultural outlook. Especially characteristic of the city of Riga and the Kurland region in Latvia’s east, however, was the group of so-called Kurland Jews who had been granted official protected status and had lived here since the 18th century and were already becoming increasingly assimilated to German culture by the beginning of the 19th century. They all enjoyed full cultural autonomy in the young nation state, as did the Russian and German minorities in Latvia.

Comparing the situation of Jews who had assimilated themselves to Russian or German culture

A good deal is already known about the situation of Jews who had become Russian-acculturated, in particular thanks to the groundwork of Dr. Svetlana Bogojavlenska, a researcher in the field of Eastern European History at Mainz University. “We know that it was the end of the Tsarist regime that gave this group the opportunity to consider themselves culturally Russian,” said the historian. Around six per cent of all Jews in Latvia used Russian as their mother tongue in daily life. A common language and education gave rise to close relationships between Russian and Jewish intellectuals. Russian-language newspapers were published by journalists of Jewish ethnicity, Jewish lawyers joined the Russian judicial association, and Jewish families sent their children to Russian middle schools.

To date, the lifestyles, paths of acculturation, identity, and acceptance by the Germans living in Latvia of the actually larger number of German-acculturated Jews have been largely ignored by researchers. About 10 percent of the Jews registered as domiciled in Latvia in 1930 stated that German was the language they used at home. In Riga, 15 percent of Jews spoke German on a day-to-day basis, 21 percent in the towns of the Kurland region. “Jews therefore contributed to the spread of the German language in Latvia, as these figures show. This is also made evident by the fact that the Jewish education authority not only operated Yiddish- and Hebrew-speaking schools but also Russian- and German-speaking schools,” added Bogojavlenska.

“Despite this highly interesting linguistic and cultural constellation in Latvia between the wars, we do not know how German culture specifically influenced Jewish cultural life during this period and how it was able to prevail,” stated project head Jan Kusber, Professor of East European History at the JGU Department of History. As yet completely unresearched is how the German populace interacted with and perceived the Jews assimilated to German culture. The historians based in Mainz assume that most Germans had their reservations with regard to Jews, even though these latter spoke their language and had an affinity to their culture. This would be in complete contrast to the situation of Russian-acculturated Jews who were accepted by the majority of educated Russian society in Latvia and were able to participate in and contribute to Russian culture.