I am what some people call a “compulsive reader.” If it is printed, and in front of me, I will read it. Flyers. Cereal boxes. Newspapers. Blogs. And most of all, books, books, and more books.

When Nancy and I came up to this suburban Bay Area town in Contra Costa County at the beginning of December to visit our son David and grandchildren Brian and Sara, we had plenty to kvell about. Brian did an outstanding job at his bar mitzvah at Temple Isaiah, a Reform congregation in Lafayette. He also played in an overtime battle in a youth league basketball game in Martinez. His younger sister, Sara, also was busy. She beautifully performed two roles in a California Academy of Performing Arts production of Piotr Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker ballet in the spacious auditorium of the Campolindo High School in Moraga.

Of course, I scoured the programs for Brian’s bar mitzvah (which was followed by a party at my son’s “Zoonie’s” candy store in Lafayette at which a video game truck was rented for the occasion). Likewise, I carefully read about the “red” and “green” casts that alternated performances of the classic ballet which is so popular during the Christmas season.

I take great delight in the fact that Sara, 11, also enjoys reading. This month, I have seen her in various positions engrossed in a book: lying on her stomach on the floor; lying on her back on a couch; totally absorbed in the stories unfolding between the covers of her books.

With her permission, I read some of the books in her collection and I found that the themes of compassion and acceptance of others predominated.

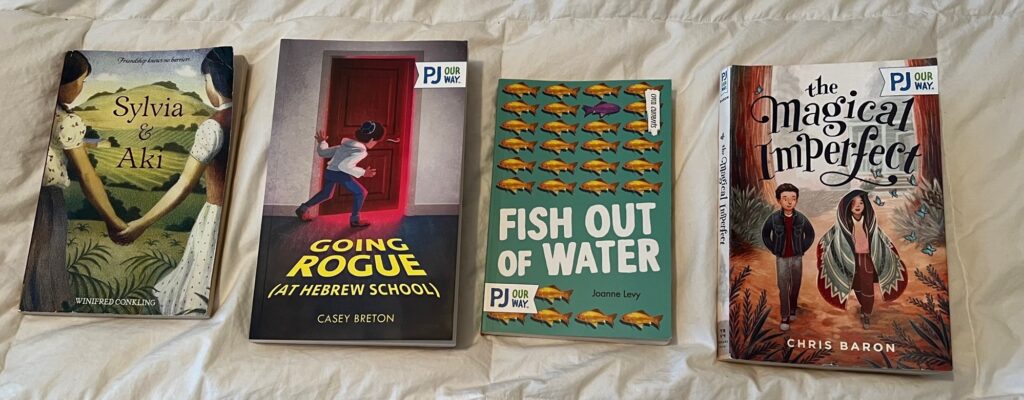

Sylvia & Aki by Winifred Conkling (New York: Random House Children’s Books, 2013) told the story of a Mexican-American girl, Sylvia Mendez, who was required to go to a Spanish-speaking school in California, even though she was born in the United States and spoke perfect English. She and her parents had rented a farmhouse from the Munemitsu family, who had been forced to relocate to a Japanese internment camp at the outbreak of World War II, even though they too were Americans. The stories of the two girls are interwoven. Sylvia meets Aki when she drives with her father to the internment camp at Poston, Arizona. Sylvia assures Aki that she is safekeeping Aki’s favorite doll. Sylvia’s father is a successful plaintiff in a suit against the school district, forcing it to stop segregating students of Mexican background. Aki and her family survive the camps and after several years of unjustifiable incarceration return to their former lives. Both girls had endured discrimination based upon their countries of national origin.

Going Rogue (At Hebrew School) by Casey Breton (PJ Library republication of 2020 Green Bean Books) tells of Avery, 10, who has three great loves in life: Star Wars, science experiments, and playing football. None of these are Hebrew school, which he views as an unnecessary distraction from all that is fun or important in his life. However, Rabbi Bob, who is on temporary assignment at Avery’s synagogue, also is a Star Wars fan and by using analogies and a demonstration with his homemade lightsaber is able to engage Avery’s interest. A subplot concerns Gideon, a klutzy, kind-hearted Hebrew school classmate of Avery’s who ends up on his youth football team, where he is bullied by a bigger boy. Rather than avoid the bully, Gideon never fails to greet him cheerfully, knowing that he might be the only person in the world who does so. Intuiting that the bully may himself be in pain, Gideon teaches Avery the lesson that people are not always as they appear.

Fish Out of Water by Joanne Levy (Orca Books, 2020, a PJ selection) tells of a boy named Fishel who doesn’t like to watch or to participate in sports. Instead, he prefers to Zumba dance with senior citizens and to knit socks like his bubbe does. His friends ostracize him, saying he acts like a girl. Fishel is determined to define himself, rather than to be defined by others. For his bar mitzvah project, he wants to knit socks for poor children who don’t know the feeling of having their feet “hugged” in yarn. The girls in knitting club come to Fishel’s aid, confronting the boys with a question of whether they are prejudiced against girls. Eventually, Fishel’s friends come to understand that diversity rather than uniformity makes the world such an interesting place.

Finally, The Magical Imperfect by a fellow San Diegan Chris Baron (New York: MacMillan Publishing, 2021) tells in free verse a fascinating story of the friendship between two children who had been self-isolating because of loss. Etan, who is Jewish, decided to stop speaking unless absolutely necessary after his mother voluntarily sought treatment at a residential facility for patients with mental illnesses. Malia, a Filipina of approximately the same age, withdrew from school after her eczema became so pronounced – with crusty skin and a swollen eye – that classmates cruelly called her “the creature.” Etan’s grandfather is a jeweler who came to the United States with immigrants of various nationalities who long ago had bonded into a polyglot neighborhood. The grandfather traces his family’s lineage to the Maharal, the wonder rabbi in Prague who created a golem to protect the Jewish people. Often running errands for his grandfather and his friends, Etan hears Malia singing behind closed doors, and after several occasions coaxes her outside. They become friends, and Eitan encourages Malia to enter a community singing contest. Gradually, with the help of some of grandfather’s magic, the two children heal each other.

Reading such stories, children learn that they can overcome adversity, stick to their principles, and find happiness. As a grandparent and as a book reviewer, I believe the lessons that we teach our children, we ought to periodically re-teach to ourselves. That’s one of the reasons I love to review books written for readers of all ages.

Republished from San Diego Jewish World.