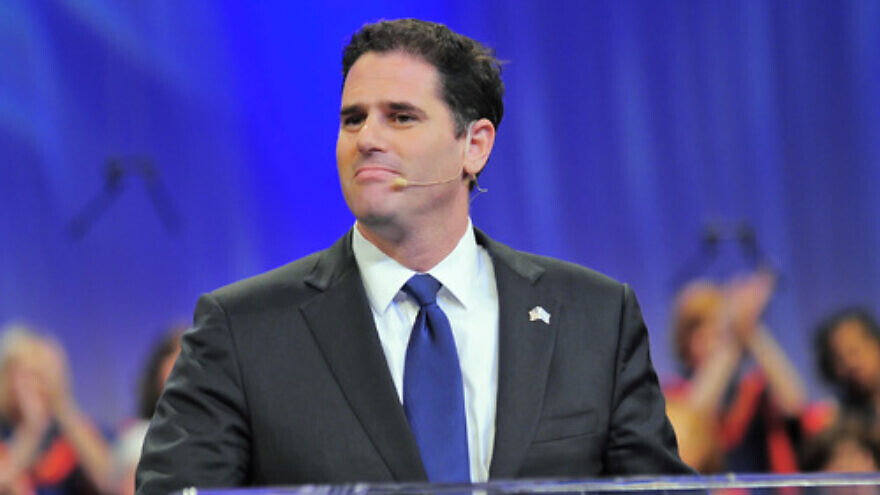

When Ron and Rhoda Dermer told their five children that this time their long stay in Washington was really over, and that there would be no more delays, they didn’t believe it. With good reason: Dermer, 50, who was slated to serve as Israel’s ambassador to the United States for three years, ended up staying in the role for seven and a half. His term officially ended on Jan. 20, 2021, the day Joe Biden entered the White House, but as he and his family were making preparations to return home, the coronavirus pandemic was sweeping the world.

“Until the wheels of the plane had touched down, the kids didn’t believe it was happening,” he said with a smile.

Dermer was born in Florida to a distinguished Jewish family that was no stranger to politics. His mother, Yaffa, was born in Mandatory Palestine to parents who fled Poland and Germany prior to the Second World War and later immigrated to the United States. His father, Jay, who died of a heart attack two weeks before Ron’s bar mitzvah, served as the mayor of Miami Beach for two terms. Ron’s brother, David, also served in the role in the early 2000s.

Prior to that, however, Dermer had spent a year in Washington working with political consultant Frank Luntz. When famous former Soviet dissident Natan Sharansky entered Israeli politics in 1995, Luntz recommended that he recruit Dermer. Dermer and Sharansky went on to develop a relationship that remains close to this day. In 2004 they co-authored a book, “The Case for Democracy,” a best-seller that was hugely influential on President George W. Bush, and even led to a surprise meeting with him.

“It was my first time in the Oval Office,” recalled Dermer. “We were in Washington on the second day of a book tour. We had no idea that Bush had read the book and was excited about it. When the call came from the White House, I started looking for a hidden camera because I was sure someone was pranking me,” he said.

“Bush would go on to include some of the ideas in the book in his second inaugural address in January 2005, and would also recommend the book on CNN. We wanted to influence American policy, so we couldn’t have asked for more. But in practice, the Bush administration didn’t implement the book’s ideas. Democracy is not just about elections; it’s first and foremost about liberty, and that is something that has not happened in Iraq, Afghanistan, Gaza or the Palestinian Authority,” he said.

It was Sharansky that made the connection between Dermer and then-Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu in 1999. Their first meeting was not particularly inspiring. It took place on the eve of elections, and the young American told Netanyahu he was about to lose to Ehud Barak.

“Netanyahu wasn’t surprised,” he said.

Their second meeting took place in Jerusalem after Netanyahu’s electoral defeat.

“Netanyahu suggested that I work with him, and outlined his philosophy on the nature of state power, based on three pillars: military power, economic power and technological power. He told me that if we are strong, we will be sought after,” said Dermer.

Dermer liked what he heard, and has been one of Netanyahu’s closest advisers ever since.

He recently joined the Jewish Institute for National Security of America (JINSA) in Washington, and is currently working on a book that he says will include many revelations.

Like Netanyahu, Dermer has a hawkish, conservative worldview, but he is not a hard-line ideologue.

“I never saw my job as having to navigate the prime minister to where I want. I always presented him with the full picture and gave him my recommendation. But the decision was always his. I bring this up because there were advisers, especially during Netanyahu’s first term in the 1990s, who tried to steer him according to their agendas, and to do so they created a distorted picture so that he would make what they saw as the right decision. That forced him to change decisions later on,” he said.

Returning to Washington

In 2005, when Netanyahu was finance minister, Dermer was appointed as economic attaché in Washington. To take the appointment, Dermer had to renounce his American citizenship. In 2009, when Netanyahu was again elected prime minister, Dermer was appointed as his senior diplomatic adviser. From then until the establishment of the new government three months ago, Dermer was involved in every significant diplomatic development, and in particular, those connected to U.S.-Israel relations.

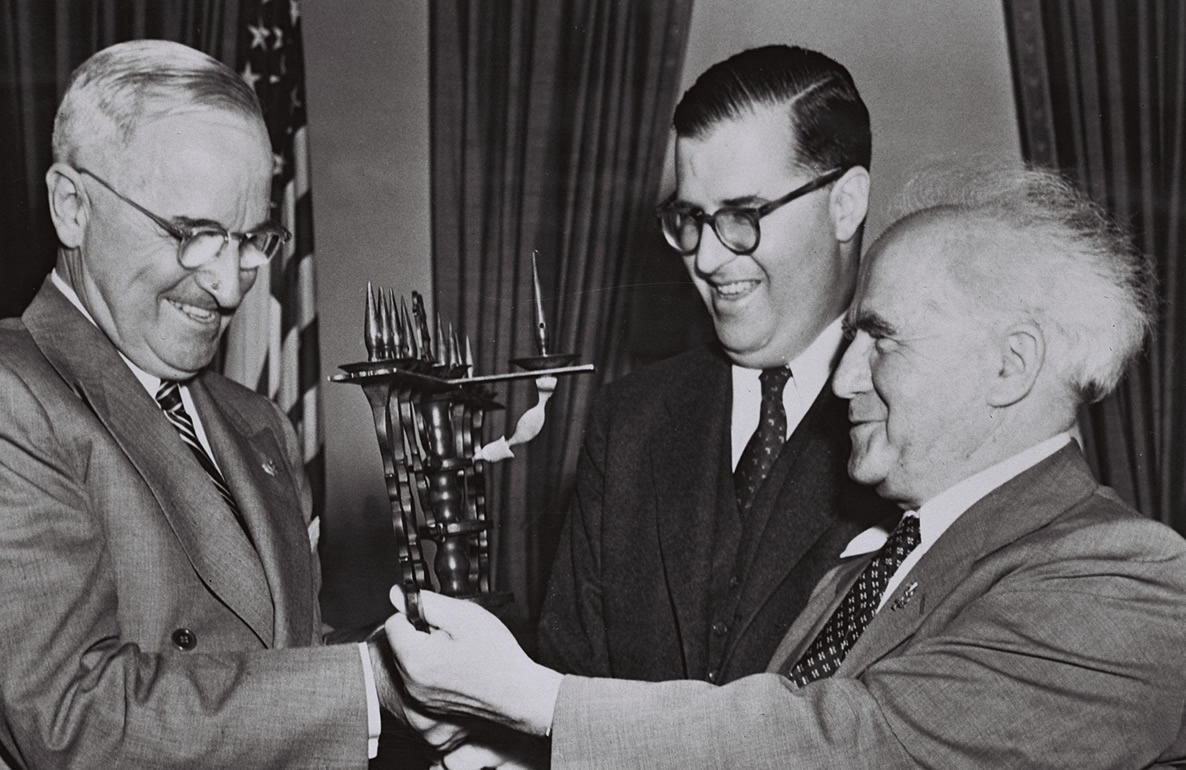

Dermer recalls, for example, a meeting in Sharm el-Sheikh between Netanyahu and then-Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak, held shortly after his famous Bar-Ilan speech. In an attempt to reject Netanyahu’s demand for recognition of Israel as a Jewish state, Mubarak brought along a copy of the 1948 U.S. recognition of Israel. The words “Jewish state” had been erased from the document and in their place, President Truman had written “State of Israel.”

“Mubarak showed us the document and said that even the United States wasn’t willing to recognize a ‘Jewish state,’” Dermer recalled. “I said to him that when Truman and his people were preparing a declaration recognizing Israel, they didn’t know what the state would be called. Therefore, in the initial draft, they wrote ‘Jewish state.’ When the State of Israel was declared, they erased ‘Jewish state’ and replaced it with ‘State of Israel.’ So, on the contrary, this shows that the Americans recognized Israel as a Jewish state. Netanyahu was happy.”

In late 2013, Dermer took up the post of ambassador to the United States. He was meant to complete his term in late 2016, but then Donald Trump was elected president. Trump, who had met Dermer at an event a few years earlier, told Netanyahu in a phone call that he liked the Israeli ambassador.

“Two minutes after their conversation, I received a call from the prime minister. He said to me: ‘You’re not going anywhere.’ I thought to myself my time will be extended for a few months, just until things sort themselves out. In reality, Netanyahu kept asking me to extend my term.”

Dermer’s standing with the American president and senior administration officials allowed him to leverage his role to generate achievements, but it wasn’t easy.

“I had an open door at the White House and there is no doubt that the Trump administration was the most pro-Israel administration ever. Trump also had the courage to make decisions that flew in the face of the rest of the world and the professional echelons underneath him. But that doesn’t mean there weren’t arguments. Every little thing is a big thing. I would recommend to every Israeli ambassador to Washington to put on his desk a small sign reading: ‘The Land of Israel is redeemed in torment.’”

Q: One of the most courageous decisions Trump took was to recognize Jerusalem as Israel’s capital. Did he consider making that move on the first day of his presidency?

A: Yes. His people spoke with me about it. I don’t know why it didn’t happen. Perhaps his security advisers opposed the idea, which is what happened when he finally made the move.

Q: How did the president come to the decision to recognize Israeli sovereignty in the Golan Heights?

A: The issue came up in the first meeting between Trump and Netanyahu in 2017, but it became urgent for us in December 2018 after Trump announced the withdrawal of American troops from Syria following a conversation with [Turkish President Recep Tayyip] Erdogan. We recognized the opportunity and for three months I worked on that non-stop.

At the time, I went with someone from the embassy to meet with a senior State Department official. He turned down the request for recognition. After we left, my colleague from the embassy said to me, “It’s over.” I replied: “With all due respect to the senior State Department official, he isn’t the one that makes these decisions. The president does.”

We should thank the president and some of the senior administration officials for American recognition of the Golan, but we should also send flowers to Erdogan.

Values vs. interests

Dermer’s first-hand experiences over the years led him to the conclusion that Israelis don’t adequately understand how the United States and the international community work.

“People use terms like ‘the Americans say’ or ‘Washington thinks’ and I ask myself: Who are these Americans that they’re talking about? Trump’s America isn’t Biden’s America and it isn’t Obama’s America. There are a lot of players in Washington. A senior official at the Pentagon isn’t necessarily America, and the president isn’t the king,” he said. “People in Israel think that if we are loved, that if we are nice, that if we only show how good our values are, we will gain support. But states operate according to interests.”

Q: So the way you see it, our ties with the United States are based on interests, not on shared values?

A: Of course there are shared values. More than that, we have a common destiny in the deepest sense, because the United States and Israel are not just countries but causes. America is what Lincoln called the “last best hope of earth,” and Israel is the hope of the Jewish people. That’s the DNA of both countries and it is the bedrock of our unique alliance.

Our common interests and values are also on that level. There were times when there was solidarity, but interests led to different results. Until the [1967] Six-Day War, U.S. support for us was mostly moral. So they also didn’t give us much. U.S. officials like to say that President Truman was the first to recognize the State of Israel, 11 minutes after its establishment. That’s true. But what they don’t say is that Truman also imposed an embargo on the sale of weapons to Israel which lasted until the 1960s.

American arms sales to Israel largely began after we proved ourselves in the Six-Day War, and it turned out that we were the best investment in the region. Over the past decade, our [value to] the United States has increased significantly. That’s the way Netanyahu sees it, and he learned it from his father, who learned it from [Ze’ev] Jabotinsky, who learned it from [Theodor] Herzl—you have to show the other powers why policies that you want supported are good for it as well.

We are more relevant to the security, economic and technological interests of the United States than we have ever been. We are the best military investment [for them] because they don’t have to send a force here to protect us. Our intelligence provides important information to the Americans and their allies. We are the second-most important technological center in the world. Our cyber capabilities are outstanding and so are our weapons systems.

That’s why I say that in the 21st century, Israel, not Germany, not Canada, not the United Kingdom and not Australia, is the United States’ most important ally. The same goes for other countries in the world—in Africa, Asia and Latin America, where Israel’s status has grown. It didn’t happen because they became Zionists; it happened because we grew stronger.

The thing that will hurt our relationship with the United States is if we are weak and we display weakness. With [the 1993] Oslo [Accords] and the [2005] disengagement [from the Gaza Strip], people thought that if we withdrew the world would support us. We got a short round of applause, but we paid a very heavy price. When we moved to defend ourselves, support for us disappeared very quickly.

That’s the reason why it’s very important to increase our might. The more our [value] grows in the eyes of the Americans, the greater the chances that they will be on our side. If in the future we find ourselves in a situation where a president wants to re-evaluate ties with Israel and the head of the CIA tells them that a rift with Israel would endanger the national security of the United States because it would [cost America] critical intelligence, and the president hears the same from the national cyber and artificial intelligence director, and others, we will know that we have succeeded.

Q: When an American president makes demands, don’t we need to comply?

A: I believe that whatever an American president says is very important, more important than anything any other person in America says. But the president isn’t a king. I believe that in order to maintain Israel’s interests we have to know how to operate vis-à-vis all the players on the chessboard—Congress, public opinion, the gubernatorial levels—and to understand how and where decisions are taken. If the approach of the new [Israeli] government is that disputes should only be discussed behind closed doors, they are making a big mistake. That kind of approach will make it difficult for us to navigate, and in the end, we will become vassals.

You have to play on the whole court, all the time. Netanyahu knew how to play the game. You have to be able to go into closed rooms and present your position there, but you also have to know how to reach public opinion, which is the key to driving moves in the United States. Netanyahu has been speaking to the American public for the past 40 years, and he is better known [in the United States] than any Israeli leader before him. Of all the leaders in the world, he is the one that understands “Rome” best.

What’s more, leaders from all over the world came to Netanyahu, and to me, with requests for us to help them navigate around “Rome.” That’s why I call him Gulliver in Lilliput.

There are a lot of smart, dedicated and patriotic people in Israel. I don’t underestimate anyone—but we have no one else like Netanyahu, who knows the international arena, and in particular America, so well. That’s a real asset for the country.

Q: No one in the Foreign Ministry, in the Defense Ministry, in the Shin Bet or the Mossad understands how the system works? Only Benjamin Netanyahu and Ron Dermer?

A: I didn’t say that. There are a lot of people who understand it and who were with us. I don’t want to name names so as not to harm them.

The Iranian threat

For most of the world, containment of Iran’s nuclear program is sufficient, said Dermer.

“They don’t see it as an existential threat for them, or they aren’t willing to pay the price of conflict. Our policy was to prevent Iranian nuclear capabilities, but the policy of Obama, Biden and the Europeans is containment. The bottom line is they aren’t willing to take military action. So if we don’t do everything we can to prevent Iran from obtaining nuclear weapons, the world won’t take care of it,” he said.

He added that lamentably, there are senior figures in the Israeli establishment who fail to grasp this.

Q: Trump also didn’t want military action against Iran.

A: That’s what the Iranians believed as well—until Trump took out head of the [Islamic] Revolutionary Guards, Qassem Soleimani. So no, I wouldn’t say that.

Q: Are the reports true that during Trump’s final weeks in the White House, Netanyahu urged him to take military action against Iran?

A: No.

Q: What persuaded Trump to withdraw from the nuclear agreement?

A: He promised to do so during his presidential campaign. In September 2017, in an address to the United Nations, he called the agreement “an embarrassment to the United States” and “one of the worst transactions the U.S. has ever entered into.” I said to Netanyahu at the time that there was no chance Trump would ratify a document that he had labelled an embarrassment.

Back then all his people opposed withdrawing from the agreement. His national security adviser, secretary of state, secretary of defense—they all tried to persuade him to stay [part of the accord] and scared him about the consequences. He was really angry with his advisers and in January 2018 he wrote to them: “This is the last time. I will never do that again and your excuses won’t work.” That was how in May 2018 it was decided that the US would withdraw from the agreement.

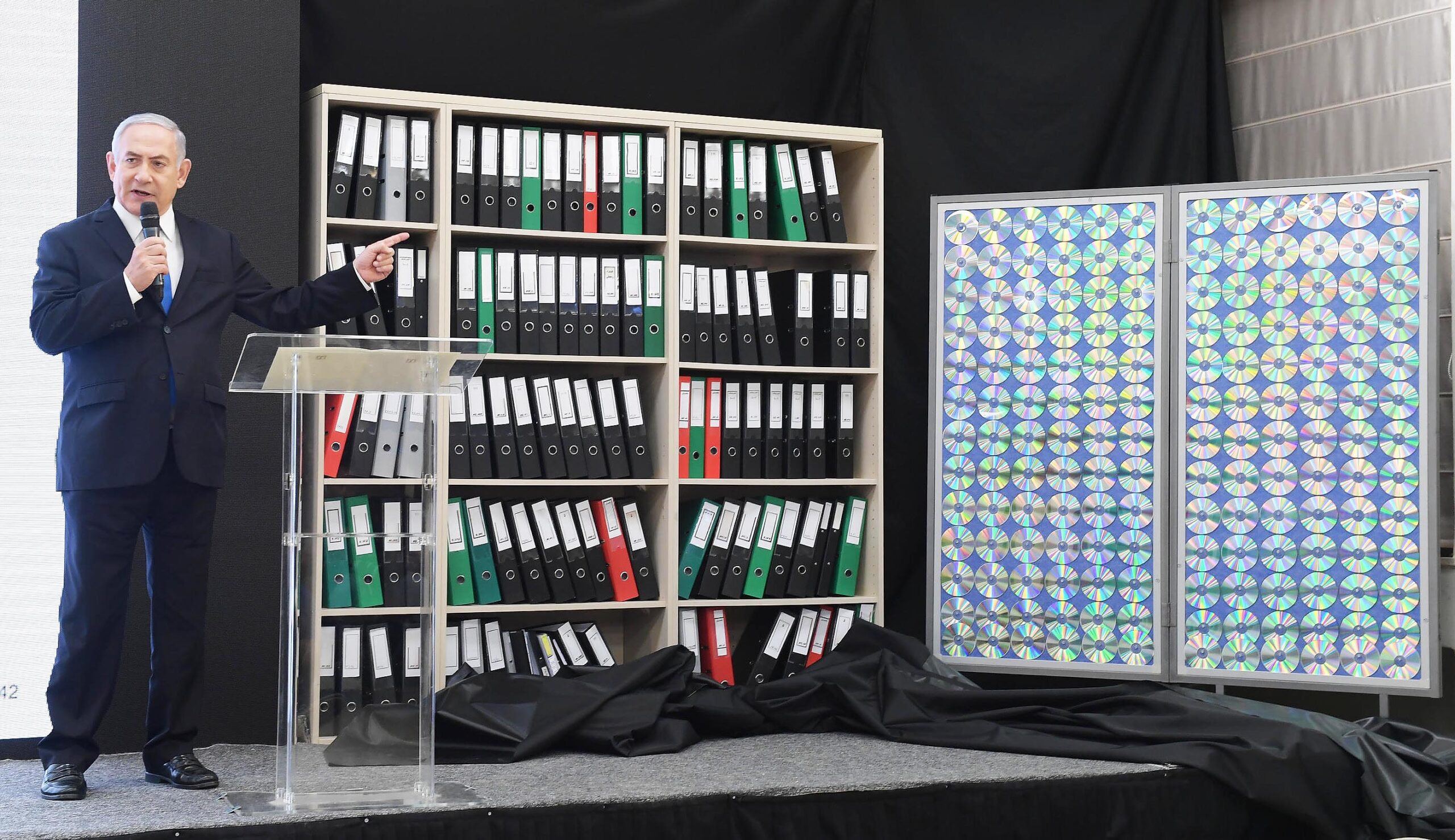

Q: So it wasn’t the material Mossad retrieved from the Iranian nuclear archives that led Trump to withdraw from the agreement?

A. No—but it certainly gave him a tailwind for the decision vis-à-vis his opponents. I don’t know anyone who changed their opinion of the agreements because of what was discovered there. Those who supported the agreement previously continued to support it, and those who opposed it continued to oppose it. But the data brought from Iran closed a lot of gaps in our understanding, and that of the rest of the world, with regard to the nuclear program. We found a lot of new sites to which the Iranians hadn’t allowed access.

Q: What was the point of fighting against the agreement? Today, three years since the U.S. pulled out of it, Iran is closer than ever to the bomb.

A: That’s not true. Most of the operations that the Iranians are currently carrying out illegally, such as [uranium] enrichment with advanced centrifuges, could have been done legitimately within a few years, according to the agreement. We are currently in the sixth year [of the agreement]. In four years’ time, [under the terms of the deal] they could have built their advanced centrifuges with permission, and they could have kept their entire [stockpile] of enriched uranium. Even Obama admitted that 12 years after the agreement, Iran’s breakout time would be zero.

Q: We would have had five or six years of quiet. We would have bought time.

A: That’s not true. First of all, quiet on the nuclear issue is misleading. You give them what they want, which is the time to complete the military program to develop an intercontinental missile that can carry a nuclear warhead—something they don’t possess at the moment. The agreement gave them the time, and the option to reach that goal in 2030.

Secondly, in the non-nuclear arena, there is no quiet at all. All the sanctions that are paralyzing their [Iran’s] economy were removed because of the agreement, which channeled billions to the Iranians and their terrorist proxies. I prefer a weak Iranian regime with a [headwind], rather than a strong Iranian regime with a tailwind.

Like I said, the world won’t stop them. After the Iranians comply with the agreement, does anybody think that the international community will stand up to them? By the way, why do you think the United States hasn’t taken any action against North Korea after it violated an agreement and developed a nuclear bomb? After all, they have the military capabilities to do so.

The reason is the price South Korea would pay in the event of a conflict. If the United States attacks North Korea’s nuclear program, it [Pyongyang] would destroy Seoul, and perhaps Tokyo, too. It won’t necessarily use nuclear weapons … but that’s the threat, that’s the risk.

You don’t want to pay that price. You don’t want to find yourself in that trap. But that’s exactly what the Iranians want—to turn Israel into South Korea and Tel Aviv into Seoul. They want to create a balance of terror so that anytime someone shoots a rocket from Gaza, we will think twice [about] whether to respond. They want to surround us with a ring of precision conventional weapons.

In the 15th year of the nuclear agreement, when you expect the international community to prevent them from getting nuclear weapons, they will have the kind of conventional might that leads people to say, “It’s too late to stop them now, they will destroy Tel Aviv.” So anyone that says that when the agreement elapses we will have all the options we do now is wrong. We won’t have options.

Q: The late Mossad director Meir Dagan said that we should only take military action when the sword is placed at our neck.

A: When the sword is placed on our neck we won’t have the option to act, because the price will be too heavy. In the [1973] Yom Kippur War, when it was already clear that war was about to erupt, Israel refrained from taking action due to diplomatic considerations, and many people paid with their lives.

In Iran’s case, we are talking about an existential threat. You cannot take that kind of risk and wait until the sword is on our necks. Iran is already becoming a regional power despite the sanctions. Think of what will happen if the sanctions are lifted and hundreds of billions of dollars are funneled into Iran’s coffers over the next decade.

We know what they are doing in Yemen, in Iraq, in Syria, in Lebanon and in Gaza. Look at the capabilities that Hamas and Hezbollah have acquired. Who will act against the Iranians in the 15th year of the agreement when they will be a lot stronger, militarily and economically?

Q: Did Dagan and then-IDF Chief of Staff Gabi Ashkenazi work against Netanyahu’s policy, especially on the Iranian issue?

A: I don’t want to name names, but there were individuals who interfered with the prime minister’s work defending Israel’s interests. That was the case between 2009 and 2012, when people worked against the military option, and between 2013-2015 in the battle against the agreement.

The American administration used senior elements within the military and intelligence establishment against the political echelon, and in particular against Netanyahu. They said, “It’s true that the prime minister believes this is a bad agreement, but there are other elements within the Israeli establishment that see this as a good agreement.” The truth is that most people within the political establishment saw the agreement as a bad one, but they weren’t willing to stand up against America. Netanyahu had the guts to do so.

Netanyahu’s appeal to the U.S. Congress

The dangers that Israel identified in the 2015 nuclear accord led Netanyahu to take extraordinary actions to block it in the United States. Dermer stood at the center of this campaign, a major element of which was Netanyahu’s address to Congress in March 2015.

The idea of addressing U.S. lawmakers was raised the previous summer by a number of congressmen, and the final decision to invite the Israeli prime minister was made by then-Speaker of the House John Boehner.

“Boehner told me that it was his responsibility to update the White House, but apparently he did so only at the very last minute,” said Dermer.

Obama and his people were furious, and Netanyahu and Dermer were portrayed as having caused a rift between Israel and the United States. Articles in The New York Times and Haaretz even called for Dermer to be declared persona non grata.

“I was proud of Netanyahu’s speech. For me it was the highlight of my term. It was a moment of ‘Who knoweth whether thou art come to the kingdom for such a time as this’ [Esther 4:14], where Netanyahu entered the king’s palace and pointed to the existential threat to his people. That is the job of an Israeli leader when he identifies an existential threat.

Q: What did the address to Congress achieve? What did your talks with senators achieve?

A: The speech helped the senators to better understand the issue. Let me remind you that in the House of Representatives there was a majority against the agreement, including 24 Democrats who opposed it. There were also 58 against it in the Senate, including Democratic senators. So in both houses there was a majority against the agreement. That majority imposed a compromise on the administration, forcing the president to ratify the agreement once every few months.

It’s true that in order to legally block the agreement we would have required 67 [votes] and we didn’t have that. But because of the atmosphere that the speech created, all the Republican candidates for the presidency, including Trump, adopted a position against the accords.

Q: One of the claims made against you and Netanyahu was that you ruined Israel’s relations with the Democratic Party.

A: Nonsense. Support for Israel grew among Democratic voters during the Obama presidency. Those are the facts. A year after the speech, support among the Democrats had increased from 48 percent to 53 percent, so the speech certainly didn’t weaken Israel’s standing among Democratic supporters. I didn’t come up with those figures, Gallup did. They have been asking the American public the same questions about support for Israel for decades.

In general, historically, there is no correlation between Israeli policy actions and the support of the American public for Israel. Support is a derivative of completely different things. For example, after the first Gulf War [1990-91], there was a peak in support for Israel, which then dropped a year later.

It’s true that there is a big gap in the measure of support for us between Republicans and Democrats. That gap derives primarily from an increase in Republican support—not from a decline in support among Democrats. It’s true that we face a challenge on the radical end of the Democratic Party, but that is the result of processes occurring within the parties, to which we are irrelevant.

People think that if we were to change our policy that would solve the problem with the progressive Democrats. That is a complete misunderstanding of what’s going on. Just as the Labour Party in the United Kingdom didn’t choose an anti-Semitic leader like Jeremy Corbyn because of us, attitudes toward Israel in the Democratic Party are not the result of things that we are doing or have done. You have to have a deep understanding of what is going on there, and not to think that the world revolves around us.

Q: That crisis didn’t harm relations between Israel and the United States?

A: No. Perhaps the best proof for that is that a year later, the administration, which was angry about the address, closed a deal with us that gave Israel a military aid package worth a record $38 billion over 10 years. Because, once again, it isn’t about emotions, it’s about interests.

Q: Prime Minister Naftali Bennett claims Netanyahu neglected to properly deal with the Iranian threat. That Netanyahu was all talk with little action.

A: This claim has no basis in reality. I saw over a period of 20 years, four of them in the Prime Minister’s Office and another seven years at the embassy in Washington, how Netanyahu brought the world on board to create international pressure on Iran. He was the one who managed to persuade many people in the international arena … because they understood that he was willing to act, and that created greater pressure. He was the most active factor in the Israeli and international arenas on this issue. There are a lot of things that are still [not publicly known]. He thought he needed to do everything [he could], and that’s how he acted.

Q: What lessons do you take away from the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan?

A: I was present at a meeting a few years ago between Netanyahu and then-Secretary of State John Kerry. Kerry tried to persuade him that Israel had no need to keep its forces in Judea and Samaria because the Palestinian Authority forces would fight terrorism efficiently. He proposed to the prime minister that he travel with him to Afghanistan to see with his own eyes “the great work the Americans were doing training Afghan soldiers.”

The implications of events in Afghanistan will continue to impact us for many years. They will impact the way the enemy perceives U.S. power and the way it perceives our power as an ally of the United States. These enemies will grow stronger and the United States will very quickly have to use force to change these perceptions, otherwise the problem will just get worse. Afghanistan also could become a country that gives shelter to Sunni terrorism from around the world.

The Trump peace plan

Dermer was also very involved with crafting the Trump administration’s proposal for peace in the Middle East, dubbed the “deal of the century.”

“Until that plan, conventional wisdom in the international arena was that the parameters for peace between Israel and the Palestinians are known, and … include the 1967 borders with territorial swaps, uprooting of communities, the division of Jerusalem and so on.

The prime minister and I sought to break that paradigm and to show that it was possible to present a different plan, one that both the Israelis and the Arab states would not reject. A plan that, in any future arrangement, would ensure Israel has defensible borders and full security control, without the return of [Palestinian] refugees and uprooting of communities. The idea behind sovereignty was to erase the old paradigm and to establish something new, that Israel could live with.

Q: Is there any chance that this peace plan could return to the diplomatic agenda?

A: If Trump is re-elected, yes. If not, perhaps it will be used as a foundation. Even this plan isn’t 100 percent. Netanyahu said he is willing to accept it as a basis for negotiation; he never said he accepts it as-is. In any event, in the foreseeable future an arrangement with the Palestinians is not feasible. Perhaps in 50 years someone will use the plan and reach an agreement.

What’s important is that we, in Israel, no matter who the prime minister is, know how to stand up for these principles. Because Oslo happened not because of external pressure, but because our leaders decided that was what needed to be done. It’s true that there are external pressures, but usually there is an internal anchor, here in Israel, to claim that withdrawal and uprooting of communities is an Israeli interest.

You can’t get elected in Israel today if those are your positions. But if tomorrow the Palestinians were to present someone who sees us as a partner, you’ll quickly see a revival of these ideas.

Q: Why wasn’t sovereignty extended to Judea and Samaria?

A: Netanyahu said from the beginning that the condition for the move was backing from the United States. In the end, we didn’t have that, even though we had been promised it. Later it was dropped from the agenda because of the emergence of the Abraham Accords.

Q: Did opposition to the plan among elements on the right contribute to the failure to enact sovereignty?

A: Look, in Jewish history, zealotry has never been successful. Even when there are principles and ideologies, you have to know how to navigate and compromise to mark achievements. When you have principles, sometimes maneuvering is difficult.

Q: Are you satisfied with the Abraham Accords?

A: A lot of things that are not true have been written about the Abraham Accords. I can tell you that under the circumstances at the time, Netanyahu, by agreeing to the proposal, turned lemons into lemonade. Sovereignty wasn’t canceled, it was suspended, and that is an important difference that we insisted on.

The main thing is that the whole world saw that four Arab countries reached normalization agreements with Israel before the Palestinian issue was resolved. That is a substantial paradigm shift. I think we improved our standing in the region, and we have only just started.

The countries that normalized ties with us in the Abraham Accords didn’t do so because of good will, but because of interests. They saw Israel’s prowess, especially in view of the United States withdrawal from the region. If America had stayed, we would be less important to them. The American withdrawal increased Israel’s equity.

And they had other problems as well. The instability in the region that bred the revolutions in Arab countries; the rise of radical Islam, both ISIS [Islamic State] and Iran; and reduced American dependence on oil. On the other hand, Israel’s growing power, including its technological strength, gave them another reason to move closer. After all, for them to boycott Israel’s high-tech industry would be like half of America boycotting Silicon Valley. It doesn’t make sense.

Another thing that contributed to the Arab countries moving closer, and I have to admit it was something I had not foreseen, was Netanyahu’s speech against the Iran nuclear accords. They really appreciated his stand against Iran.

Q: Did Israel agree to the U.S. sale of F-35 fighter jets to the UAE in exchange for the peace agreement?

A: Absolutely not. The UAE was interested in various weapons systems for years, and we knew that they would request them after the agreement. But all along we told the Americans that if Israel’s qualitative edge was undermined, we would actively oppose the sale of such systems. The administration committed that there would be no violation of our qualitative edge.

After the Abraham Accords were signed there was indeed a request from the Emirates for weapons systems. Only then did our defense establishment sit with the relevant officials on the American side. Once agreements were reached on weapons systems, we said we would not oppose them, but only then, and not a second before. The claims that we agreed to the sale of the aircraft early on are quite simply libelous.

Q: You played a major role in the release of Jonathan Pollard from jail and his ability to make aliyah.

A: I visited him in jail shortly after taking office. I didn’t publicize it, so as to maintain his trust, and that helped. I was the only Israeli official in contact with him during those years. He felt that Israeli representatives had used him for political reasons.

During the Trump presidency, when Pollard was living in New York, we wanted him to be allowed to make aliyah to Israel. Every few months we approached them about it. Netanyahu wrote letters to the president, each time noting that this would bring an end to an affair that had clouded relations between the two countries for so many years. Trump was close to taking the decision, but then reports appeared in the American media that Israel had installed listening devices near the White House—something that of course wasn’t true.

It was clear to me that these reports were aimed at holding up his release. In the end, right at the very last moment, I realized that it would be better to wait until November 2020, the date when Pollard was due to complete five years [of parole] in New York, and then simply to once again ask them not to interfere or take any action.

The people who really helped were Trump’s chief of staff, Mark Meadows, and the late Sheldon Adelson and his wife Miriam, who spoke about the issue personally with the president. Right up to the last moment we didn’t know if it would really happen. But in the end, it worked out. A lot of things happened with Pollard; there’s enough there to fill a book.

Q: You have also been linked to the support Israel receives from Jews and evangelists in the United States. You have been quoted as saying that evangelists and Orthodox Jews should be seen as Israel’s future allies, while the rest of the Jewish community is a lost cause.

A: That’s another case where I was misquoted and mistranslated. What I said, and what I think, is that we don’t invest enough in evangelists. They make up a quarter of the U.S. population, and their support for Israel is enthusiastic and unconditional.

As for the Jews, they make up about 2 percent of the general population. We are top of the agenda for some of them, but for a large section we don’t even make the top five or top 10.

It’s true that some Jews lend Israel their absolute support, but there are Jews who are Israel’s biggest critics. From a political point of view, the evangelists are the backbone of American public support for Israel. Whoever cannot see that is not looking at reality.

I don’t think these two publics are comparable. Obviously, the connection with the Jews is part of Israel’s DNA. We are connected to all the Jews in the world by an umbilical cord; they are our family and they are potential citizens, and that is how we should relate to them. It’s true that their political strength is small, but we have to listen to their voice, because their standing is different to that of non-Jews.

What I say to Jews in America, both to the leadership and the public, is if you support Israel 95 percent of the time, and you also have criticism, the Israeli public will listen to that criticism. But if you raise your voices just to criticize Israel, and your support for Israel isn’t heard, the Israeli public won’t listen to your criticism. That’s my view.

Q: So from your perspective, what does it mean to be “pro-Israel”?

A: The way I see it, the question is whether you want to believe the [best] about Israel or the worst about Israel. Being pro-Israel means wanting to believe the best about Israel, and demanding the burden of proof [to the contrary] from our enemies.

This is an edited version of an article that first appeared in Israel Hayom.