A substantial portion of the following story appeared in “Messages by Regular Folk on 1918 Pandemic” online in Postcard History on August 22, 2021. That publication’s editor gave permission to reprint it in the cause “that all learning should be shared.” San Diego Jewish World editor Donald H. Harrison encouraged any Jewish references, which appear immediately below.

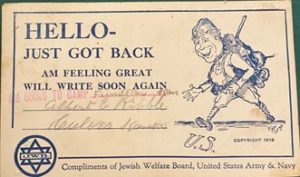

The Jewish Welfare Board was created on April 9, 1917, three days after the U.S. declared war on Germany. It wanted to provide services to Jewish troops similar to what Catholic servicemen received from the Knights of Columbus and Protestants from the YMCA. In 1919, after the war was over, the JWB printed tens of thousands of these reassuring cards depicting a grinning doughboy and distributed them to servicemen to send to family and friends.

The Armistice was signed on November 11, 1918. The guns were silent, but there lurked another unnamed killer. The cue is the expression, “AM FEELING GREAT.” As my grandfather a German surgeon in the Great War noted in his account of military medical care, more service people died of disease than battle wounds, and in the closing months of the war the enemy was the influenza. The American presence in Europe ended on January 3, 1920.

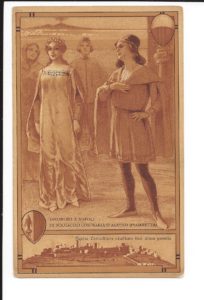

Giovanni Boccaccio began to write his Black Death novel The Decameron in the late 1340s. My reading in the late 1950s left a lifelong impression. COVID-19 refreshed my interest in pandemics. The adjoining 1913 Italian postcard celebrates the sixth centenary of Boccaccio’s birth in Certaldo, a village near Florence, Italy.

Giovanni Boccaccio began to write his Black Death novel The Decameron in the late 1340s. My reading in the late 1950s left a lifelong impression. COVID-19 refreshed my interest in pandemics. The adjoining 1913 Italian postcard celebrates the sixth centenary of Boccaccio’s birth in Certaldo, a village near Florence, Italy.

The three phases of the 1918 Influenza epidemic appeared at different times and different places between January 1918 and 1920. In the United States the devastating second wave, October-November 1918, occurred as the war was coming to an end.

The Delta variant of COVID 19 reminds us nature’s unpredictability and our vulnerability. The centenary of the catastrophic 1918 misnamed “Spanish Flu” revived interest in pandemics. Postcards provided a voice for ‘regular folk,’ a term borrowed from American Holiday Postcards, 1905-1915, Imagery and Context (2013) by Daniel Gifford. Senders with a postcard and two cents postage shared flu experiences with friends and relatives.

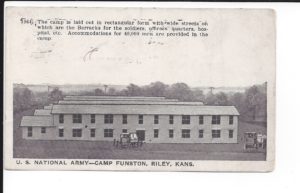

Country doctor Loring Miner reported influenza in January 1918 in Haskell County, Kansas. It is unclear whether the influenza started in Kansas, France or China, certainly not Spain. Public health officials initially downplayed the flu’s severity but soon called for masks, closing schools, churches, saloons, restricted travel, and enforced quarantine. Some egregious mask-slackers were prosecuted, fined or imprisoned. The flu filled newspapers with sad stories.

In early February ‘ill, sick, feeling bad, and flu’ started appearing on postcards. October-November reported the merciless second wave. December saw some tapering off.

On February 9 Frank wrote from Tacoma, Washington to Albany, Oregon, “Dear Auntie, how did you enjoy the flu. It is some flu ha.” They would not be laughing long.

Frederick N. Funston (1865-1917) Major General in the U.S. Army received the Medal of Honor for service in Spanish American and the Philippine-American War. His name adorned two military establishments, Fort Funston, Harbor Defense Installation in San Francisco in 1900, and Camp Funston in Fort Riley, Kansas, in 1917. Camp Funston may have been the early epidemic epicenter.

Mama wrote on this postcard postmarked, February 22, 1918 Junction City, Kansas, 13 miles from Funston, to Mrs. Helen Wherry in Danville, Illinois: “Hello How are you….Tod comes over to see me every day. He just left – say he is sure happy as a king to think he is getting well. Tell Josephine there is a sweet little girl here. She is sick. Now vaccination. Mama”

The epidemic reached it apex. During October 195,000 died.

Messages included “Dear Mother, Amusements closed because of the ‘Flu’.”

“Dear Friend Claude, I am having a fine time but cannot go south on account of the ‘Flu’.”

“Dear pappa and mamma, I am still in the hospital…”

“Dear Gladys, The flu has been very bad here, but is decreasing now.”

Will at Camp Dodge, Iowa wrote to Corp. Victor A. Read in the Army Expeditionary Forces in France on October 12 that he saw John who was laid up in the hospital with pneumonia. “Can’t tell how it may turn out yet. He is feeling better today. Mother is going to stay here for a week or so. The camp is quarantined. I’m not going to expect the worst anyway.”

Halloween is popular for wearing masks, dressing as goblins and witches, and carving scary pumpkins. On October 11, Edith in Waterford, Pennsylvania wrote on a Halloween card to Florence in Clay, New York, “Hope you have escaped this dreadful disease. The schools etc have been closed a week. We are both well now.”

Americans sent colorful Thanksgiving greetings. “Dear Cousin, Everybody is well now but Aunt Liz was sick when I came up.”

Americans sent colorful Thanksgiving greetings. “Dear Cousin, Everybody is well now but Aunt Liz was sick when I came up.”

A Third grader wrote in large letters “My dear friend, We are all well. Hope this will find you the same. We haven’t got the fleu [sic] yet.”

Alice in Bristol, Iowa wrote to Franklin, New Hampshire, November 27: “Dear Eva, The influenza about the same. Aunt Mamie was a little better yesterday but James and Gertrude also Donald have got it. Mr. Peasley and Healey and the Joudro family are the only ones up our way so far that have it.

On November 29, George Weber in Staten Island wrote in German to Ardie in the Bronx 38 miles away, Liebe Ardie – Habe gehort das du krank warst. Hoffe das du wieder gesund bist, George Weber. Translated – “Dear Ardie. Have heard that you were sick. Hope you are better.”

On November 29, George Weber in Staten Island wrote in German to Ardie in the Bronx 38 miles away, Liebe Ardie – Habe gehort das du krank warst. Hoffe das du wieder gesund bist, George Weber. Translated – “Dear Ardie. Have heard that you were sick. Hope you are better.”

President Wilson’s Thanksgiving Proclamation invoking God four times praised the righteous Allied Victory, but had not a word about influenza. The President would catch the flu in Paris.

Christmas greetings were subdued. “Dear Brother, I had been sick so I couldn’t ans your letter….wishing you a merry Xmas.”

“Dear Coz, We are all pretty well. Mother and I were planning to start for Mo last night and they have the flu down there so bad they wrote us not to come at present.”

“Dear Mother, My cold is no better but am still doctoring it.…one of the fellows of my company is almost dead with the ‘flu’.”

“Dear one all. We are all well but sorry to hear Ella had the flu. Hope she is better by this time.” Christmas Eve, Mother wrote “Dear Oscar, Hope this finds you well. I am just getting over the Flu. We have been sick for two weeks.”

Ushering in 1919 brought further greetings. Althea in Connoquesnessing, Pennsylvania wrote to Mrs. Milton Gray in Salem, Ohio, on December 29: “Dear Aunt, How I do wish you people could come and visit us….Sister Dale has been very sick but is some better.”

Ushering in 1919 brought further greetings. Althea in Connoquesnessing, Pennsylvania wrote to Mrs. Milton Gray in Salem, Ohio, on December 29: “Dear Aunt, How I do wish you people could come and visit us….Sister Dale has been very sick but is some better.”

J. E. Peck in Newton Center, Massachusetts wrote a New Year’s Eve greeting on December 31 to J.J. Young in Saco, Maine, Although I said I would be in New Year’ Day, I cannot resist the temptation to stay another day. Will report for duty Friday. All the schools are closed around here. “Flu”

Messages and images carrying flu missives reveal inconvenience, disruption, cessation of travel, closing of schools and worse. They were silent on the war’s progress, victory and Armistice. Despite chaos they remained cautious, optimistic, even joking, taking events in their stride.

The 1918-20 Influenza death toll was 50 to 100 million world -wide, Some 675,000 of America’s about 103,000,000 population died. The second decade of the 20th century had newspapers and the U.S. Postal system. A hundred years on our communication infrastructure has added radio, television, the internet, email, and expanding digital services. It is no consolation that we are approaching 675,000 against a population of about 331,000,000.

Republished from San Diego Jewish World