Avant-garde artists Lucy Schwob and Suzanne Malherbe advertised the fact that they were stepsisters, and hid the fact that they were lovers; their practice in deception useful in hiding their World War II roles as anti-occupation propagandists in Nazi-occupied Jersey.

Wealthy enough to own an art-filled, large Jersey manor with a view to the French side of the English Channel, Lucy and Suzanne — who the likes of Salvador Dali, Aldous Huxley and Jean Cocteau knew in pre-war Paris respectively as the artists Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore–thought they’d wait out the war on the quiet British-owned island within a few nautical miles of the French coast. But not long after German forces overwhelmed the Channel Islands, temporarily leaving the British home islands impotent and frustrated in any desire to liberate them, Schwob and Malherbe decided to become a two-woman resistance force.

They didn’t blow up bridges, or kill anyone with well-executed sniper attacks. Instead, they used their imaginative talents to produce creative pamphlets, leaflets, and loose leaf magazine inserts, ostensibly written by a “Soldier of No Name” calling on German enlisted personnel to disobey their superior officers, desert, and rejoin their exploited families back in Germany. They produced so many of these leaflets, which they ingeniously snuck into mail, bookstores, and cafes, that the Nazi occupation force came to believe there was an active cell of traitors among their soldiers. Written in German (which Malherbe spoke), initially the propaganda gave no cause for any suspicion against the quiet step-sisters who, as well-to-do inhabitants of the island, received unusual deference from the occupying force. One of their more daring early morning capers was mounting a banner in a church where many soldiers worshiped that proclaimed, “Jesus is Great — But Hitler is Greater. Because Jesus Died for People — But People Die for Hitler.”

It was a dangerous business they were engaged in, doubly so for Schwob, whose father in Nantes, France, was a well-known Jewish book seller. An independent spirit, Schwob followed neither her father’s Judaism nor her mother’s Christianity, although she was familiar with both.

The thin tissue paper which could be rolled multiple sheets at a time into a typewriter was what gave them away — the shopkeeper who sold them their supplies tipped off the authorities, resulting in their inevitable arrest.

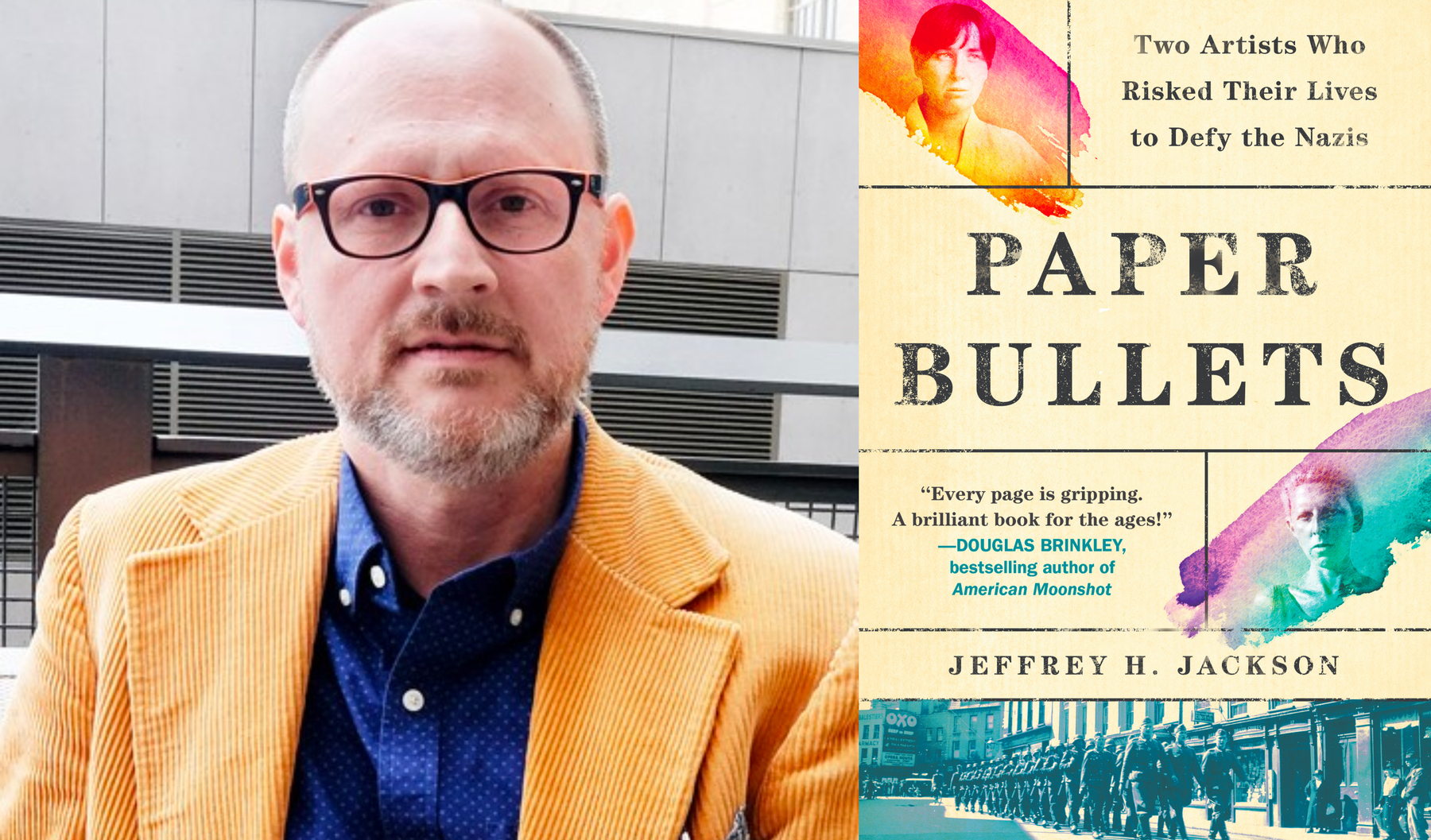

As one can see from the endnotes, author Jackson is a meticulous historical researcher, who combed numerous archives to piece together Schwob’s and Malherbe’s secretive career. Jackson also writes with the grace of a novelist, making the two lovers’ stories read like a suspense novel. He followed them into the prison where they were kept on Jersey, introduced us to their diverse jailers and cellblock mates, and provided us with seats in the courtroom where, near the end of the war, they were put on trial and initially sentenced to death.

Schwob and Malherbe freely admitted their acts of propaganda sabotage, refused to sign a confession typed up by their captors, and also rejected suggestions that they appeal for clemency. The occupiers were nervous about executing women — which hadn’t been done in centuries since “witch trials” were conducted on the island of Jersey — and feared creating a popular uprising after the Allied invasion of France on D-Day left Jersey cut off from the shrinking German control of the European continent. So, the authorities commuted their sentences to long years of imprisonment — which turned out to be moot after the Germans surrendered to the Allies, and in the process returned to Britain the Channel Islands.

Reading this historical account, you will marvel at the mental fortitude of the two stepsisters, who were kept apart in prison but who found ways to comfort each other. And you’ll appreciate the artistry of author Jackson for a historical tale, very well told indeed.

Republished from San Diego Jewish World