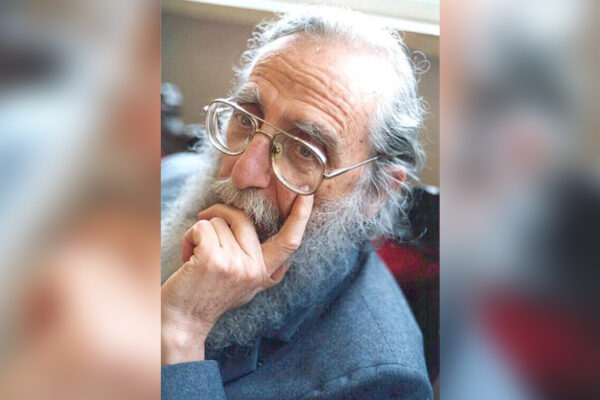

For Israeli Philosophy Professor Shalom Rosenberg, the world is divided into two kinds of people: those who had the privilege of meeting Monsieur Choucani and those who did not.

An enigmatic scholar, Choucani taught many distinguished students in Europe, Israel and South America after World War II. Besides Rosenberg, his disciples were French Jewish philosopher Emmanuel Levinas, Holocaust survivor and Nobel laureate Elie Wiesel, and more.

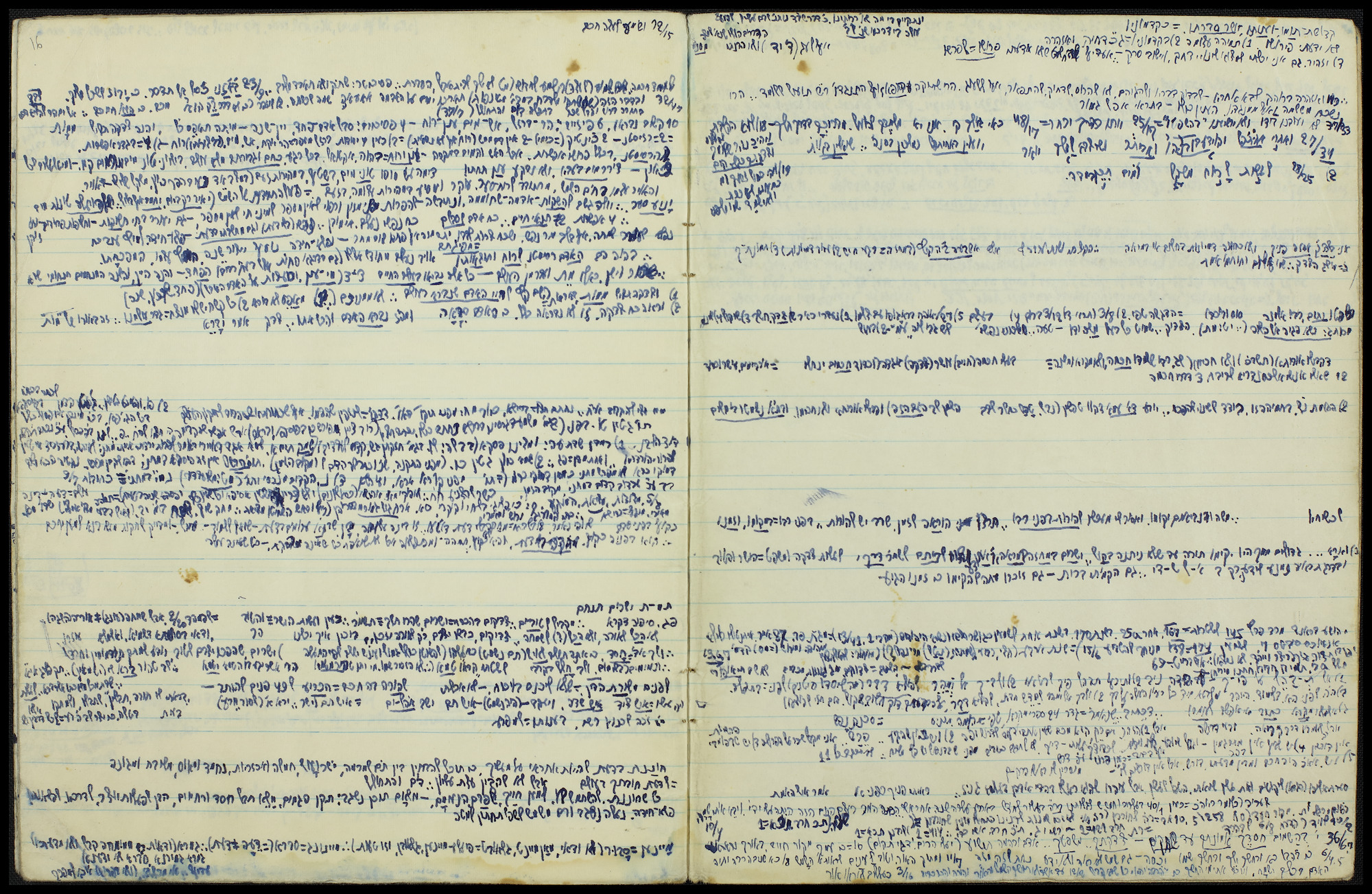

“Choucani’s notebooks are a gold mine,” said Yoel Finkelman, curator at the National Library. “His works are exceptionally challenging to decipher because he did not write orderly paragraphs. He put down parts of sentences, mathematical equations, and acronyms in which he encrypted his ideas,” added Finkelman.

According to Finkelman, the library worked on deciphering Choucani’s works in order to “understand what he knew, how he thought and how he formulated his religious and educational views.” He also said the library considered it “of paramount importance to bring to the public’s attention the story of one of the most mysterious and influential figures in twentieth-century Jewish thought.”

David Lang, an archivist at the National Library, said another aspect that made the process of deciphering Choucani’s notebooks complex was how diverse his knowledge was.

“The notebooks cover all subjects in Judaism—Torah, Talmud, Jewish law, rabbinic literature, philosophy, Kabbalah, ethics and Hassidism,” said Lang. “He also spent a great deal of time on mathematics and physics, and Choucani’s interest in the history of science is also evident,” he added.

According to Lang, Choucani had a photographic memory and was able to recall and cite the entire Bible, Talmud and various Jewish texts from memory, and had also mastered several languages.

Wiesel, who greatly admired his teacher, wrote that Choucani “mastered some thirty ancient and modern languages, including Hindi and Hungarian. His French was pure, his English perfect, and his Yiddish harmonized with the accent of whatever person he was speaking with. The Vedas and the Zohar he could recite by heart. A wandering Jew, he felt at home in every culture.”

For Rosenberg, who was born in Buenos Aires in 1935 and moved to Israel in 1963, meeting Choucani was a dream.

“Shalom spoke about Choucani all the time, and so in 1967, I surprised him with a gift—a trip to Montevideo, Uruguay, to meet him,” said his wife Rina. Despite the limited amount of time they spent together, Choucani left a tremendous impression on Rosenberg, as well as on the rest of his students.

Choucani arrived in Uruguay after spending several years in Israel, Algeria and France. While in Israel, he studied with renowned Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook, who was the first Ashkenazi chief rabbi of British Mandatory Palestine.

Kook called Choucani “one of the most excellent young people … sharp, knowledgeable, complete and multi-minded.”

His comprehensive knowledge even helped him escape the horrors of the Holocaust. When arrested by Nazi officers in France, he claimed he was a Muslim. Doubting whether that was true, officials summoned the chief mufti of France at the time, who, after a three-hour conversation with Choucani, declared he was “a holy Muslim.”

The Jewish scholar eventually made his way to Uruguay, where he died unexpectedly in 1968.

“He felt that Uruguay was so far away, the war would never spread to there,” said Rina Rosenberg. In 1968, she and her husband participated in a Jewish teachers’ seminary in the South American country, which Choucani also attended.

“He used to always sit in his room and teach,” she said. “He never came to the dining hall, but only ate in his room. He was charismatic and impressive. Shalom told me Chouchani told him he preferred to teach women because he said their heads had not been tainted by yeshivas.”

Choucani passed away during that same seminar.

“One Saturday night he suddenly fell ill,” Rosenberg recalled. “Shalom and a few others took him to a local hospital, where he died. Shalom was devastated. He thought Choucani could have been saved, but the hospital didn’t even have oxygen to give him.”

Rosenberg, who is the former chair of Jewish Thought at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, has spent many years deciphering Choucani’s work. He asserts that Choucani’s real name was most likely Hillel Perlman, and that he was born in the Belarusian town of Brisk.

A few years ago, he was joined by his student Hodaya Har-Shefi, who wrote a thesis on Choucani and is now writing a doctorate.

By studying Chouchani’s work, she learned that “he gave a lot of attention to the teacher-student relationship. It is also interesting to see his attitude towards the sages, how he criticized their work, but at the same time, deeply respected them.

According to the National Library, Choucani challenged his students with difficult questions and encouraged them to improve and progress, and especially to think in unexpected ways.

“Choucani did not want his works to be published in his lifetime,” Har-Shefi continued. “He also did not like students taking notes and summarizing his lessons. He had tremendous respect and caution for the written word.

“He wanted people to teach and learn the right way, and he tried to pass on these tools to his students to make sure Jewish tradition continues.”

Professor Hanoch Ben-Pazi, who walked Har-Shefi through her thesis work, says Choucani’s personal experience mirrored that of European Jewry who moved to the West in the first half of the 20th century.

“Choucani belongs to the same group of young people from Eastern Europe who came to the West and admired the Enlightenment and the vast knowledge that was now available to them,” he said. “The same thing happened to Rabbi [Joseph] Soloveitchik, Abraham Joshua Heschel and the Lubavitcher Rebbe [Menachem Mendel Schneerson.]”

Soloveitchik, Heschel and Schneerson were all born in Eastern Europe, but immigrated to the United States in their youth and went on to become the greatest Jewish leaders of the 20th century.

“They all tried to preserve the Torah world, but still wanted to be part of the enlightened world,” Ben-Pazi continued. “This is a complicated task. In the end, each of them had their own journey.”

Ben-Pazi has also spent a great deal of time deciphering Choucani’s works.

“It is clear that from a historical and biographical point of view that Chocani’s is a classic Jewish story,” he said. “On the other hand, seeing how his teachings affected his students and where it led them, we see that his influence on Western thought, albeit indirect, is much greater than one would assume.”

This article first appeared in Israel Hayom.