The last neighborhood Judaica store in Manhattan is ready for the High Holidays.

Long, twisted Kudu shofars—made from the horns of the African antelope—hang dramatically from the ceiling. But small rams’ horns are still the biggest sellers, says Shlomo Salczer, a buyer in the gifts department, pausing to give instructions for folding a kittel, the white garment traditionally worn during Yom Kippur services and during Passover seders.

A legacy business established in 1934, West Side Judaica & Bookstore is itself an endangered species. Prohibitive Manhattan rents and competition from the web have made a family store like it all but untenable, Salczer says. (His brother owned the shop for 40 years before selling it to his brother-in-law in 2017.)

“Business is not like it used to be. The rent’s going up, so I don’t know what’s going to happen,” he laments. Amazon and other online retailers knocked out its last competitor, J. Levine’s Judaica, in 2019, leaving only a couple of boutique galleries and gift shops.

Even as the Upper West Side transformed from an immigrant enclave to a gentrified playground for yuppies, the Salczers’ store has remained a fixture. “Religious, not religious, we cater to everybody,” he says.

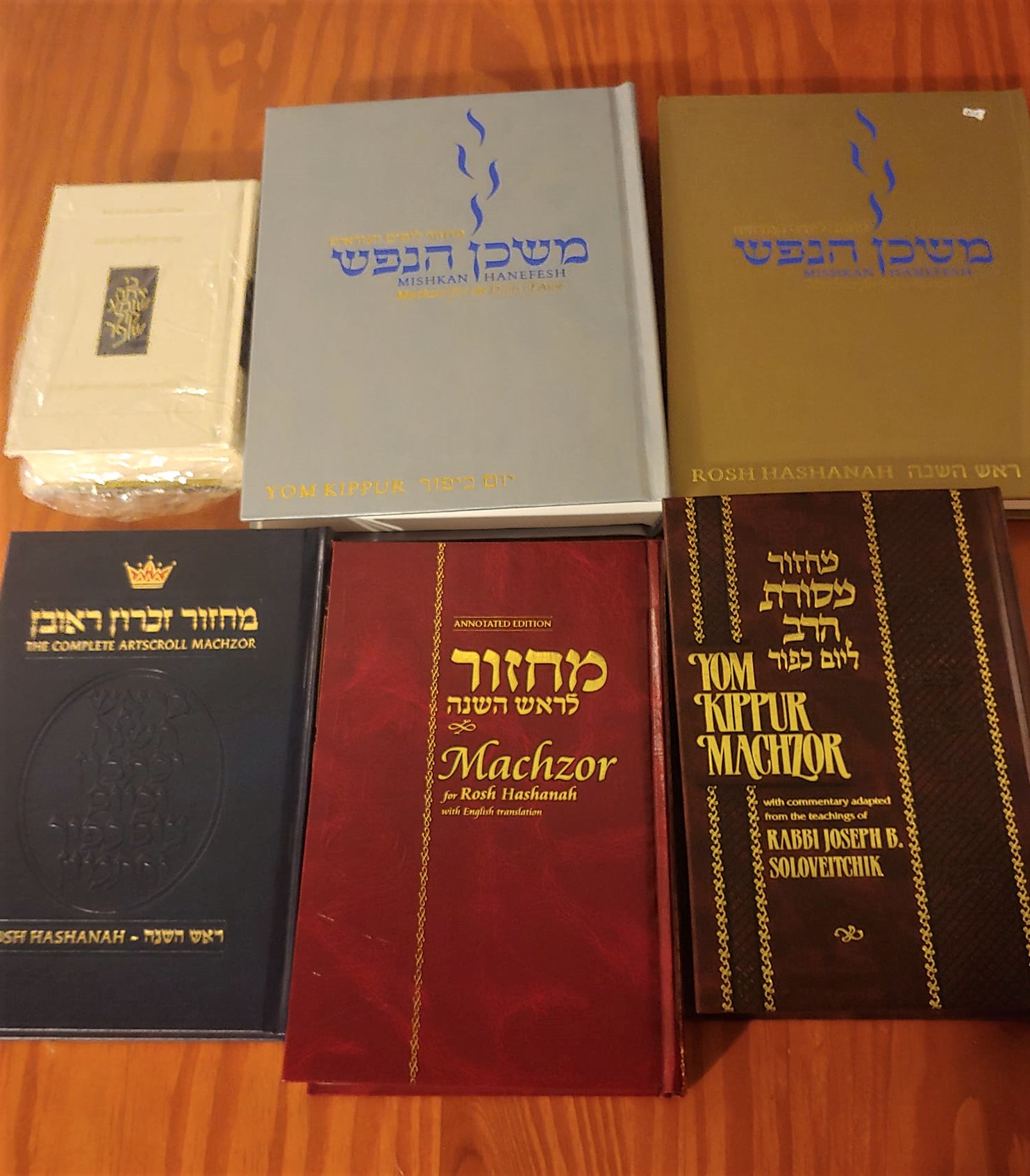

Large Judaica stores still flourish in Chassidic neighborhoods in Brooklyn, but those like West Side Judaica, which draw in a diverse clientele—stocking everything from biblical criticism to the traditional Artscroll Chumash—are struggling. Post-pandemic, the market has moved definitively online, where retailers offer convenience and prices that small stores struggling with large overhead costs can’t hope to match.

In the process, however, something is being lost, insists Salczer. In-person experiences with Judaica—and other Jews—that might not happen elsewhere: “Talking, shmoozing, trying on a tallit, seeing the [mezuzah] parchment, feeling it.”

The daily afternoon prayer service hosted in the store attracts strictly observant Jewish men who wear black hats, as well as those who only don a kippah for prayer. Both sorts are comfortable in the shop’s neutral environment, he notes.

That communal function keeps West Side Judaica’s doors open, even when turning a profit has become a distant dream.

“A Jewish neighborhood without a Judaica store is embarrassing,” says Salczer.

Selling scrolls in San Francisco

San Francisco isn’t known for its Chassidic neighborhoods, but it does have a Judaica store.

“In the Bay Area, we have a lot of non-affiliated people who are still culturally Jewish and want to put up mezuzahs,” says owner Hiroko Nogami-Rosen. “I often give them advice on how to put it up and what’s on the scroll.”

A Tokyo native, she opened her store, Dayenu, in 2004 when she couldn’t find bat mitzvah gifts for her daughter’s friends. Housed in the Jewish Community Center of San Francisco, Dayenu—like many shops in synagogues across the country—benefits from a sympathetic landlord. “They gave me a really good break,” she says. “That’s how I’ve been staying here.”

In Dayenu’s case, the store came first … and then the community. The fact that Nogami-Rosen wasn’t Jewish didn’t prevent her clientele from coming together when she was diagnosed with breast cancer shortly after she opened the shop. “The Jewish community was very, very supportive,” she recalls. “I made friends.” She said that she was so moved by the experience that she decided to convert.

But two decades later, Dayenu’s customer base has dwindled to senior citizens and parents from the JCC’s preschool. “I’m not making a living. It’s more like volunteering my time,” Nogami-Rosen says wryly.

The freshly baked challahs she sells on Fridays don’t move quickly anymore, and her favorite items—colorful, hand-woven tallitot—are getting harder to find. “In the last 10 years, most of the Judaica artists who supplied us closed up or retired,” she says. “Young artists just don’t come to us.”

Where young Judaica artists are going is no secret. Amy Kritzer Brecker, president of ModernTribe.com, reels off some of her more interesting suppliers: a company in South Africa making ethically sourced African menorahs, a young woman in Brooklyn who uses her degree in fashion design to create acrylic Jewish jewelry, a Reform rabbi who makes holiday-themed nail decals (who is also the inventor of Instagram-famous matzah pajamas, predictably followed by sleepwear for every holiday).

Even with the occasional in-person pop-up and an active Instagram account, Brecker, who also lives in San Francisco, acknowledges that ModernTribe can’t replace brick-and-mortar Judaica stores.

“I definitely agree there’s a lot of community around Judaica,” she says. But with or without community, ModernTribe is thriving—the store has grown every year since Brecker and her brother purchased it in 2016.

‘It’s a struggle’

There are times when a Judaica store is indispensable. In late October of 2018, Pinsker’s Judaica Center—the last independent Judaica store in Pittsburgh—was flooded with customers. Workers filled endless orders for memorial candles, while the store’s in-house cafe struggled to feed the throngs of mourners who descended on the city in the aftermath of the shooting that month of 11 Jewish worshippers at the Tree of Life*Or L’Simcha Synagogue.

“We felt it in a big way,” recalls co-owner Baila Cohen. “It’s a small enough city so that people really do have contact with one another.”

Five years later, however, Pinsker’s is facing the same challenges as other Judaica stores around the country. “We’re still working to stabilize and continue,” she says. “In terms of the bottom line, it’s a struggle.”

On New York’s Upper West Side, the struggle has often seemed to be approaching the end. In 2017, West Side Judaica announced that it was closing permanently. The news generated an outpouring of love and support for the store—so much support, in fact, that the owners decided not to close after all. The 100-plus comments posted on the 2017 closing announcement read like a love letter to in-person Judaica shopping.

“I love speaking with the salespeople and even other customers,” one reads. “Every time I walk into WSJ, I feel like I’m getting a tune-up on my Jewishness.”