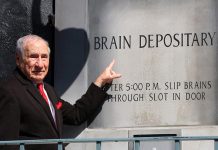

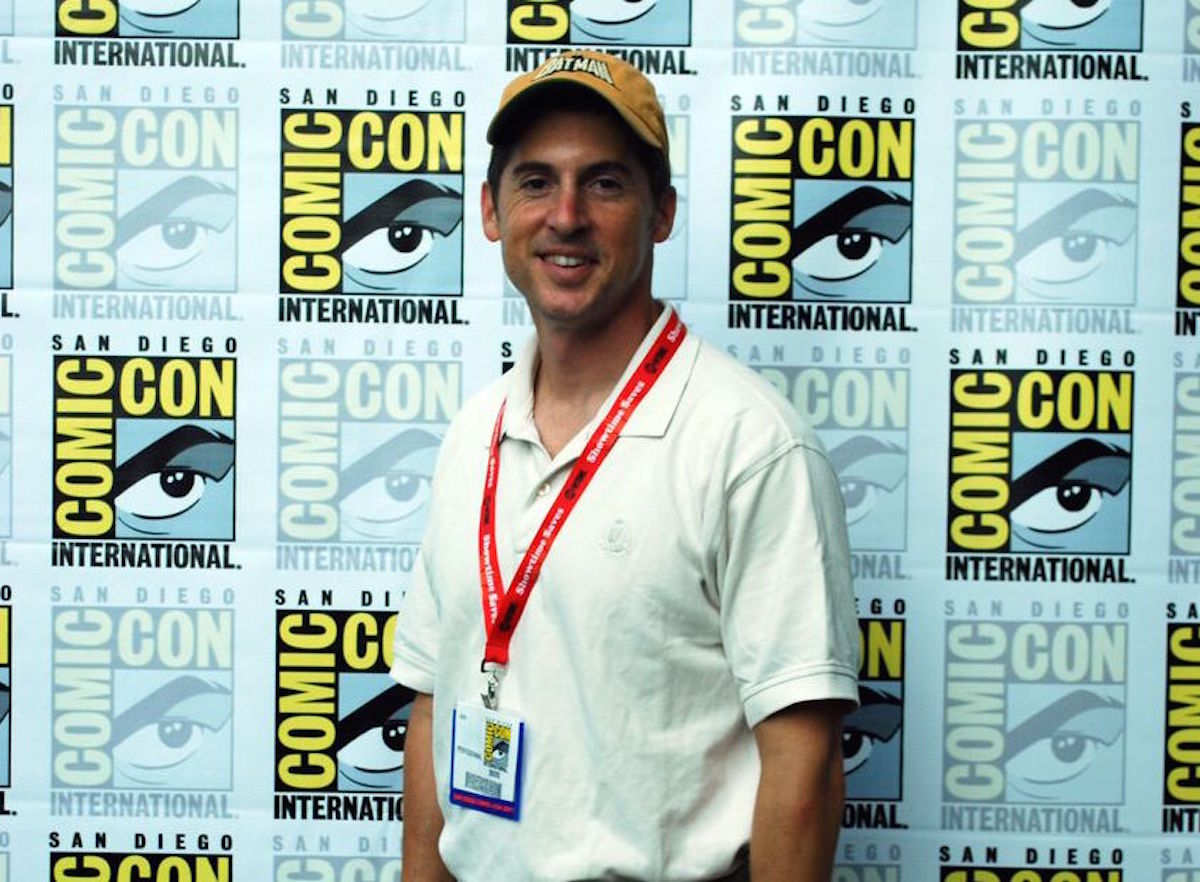

Superhero comics have been influenced greatly by Jewish life in the United States and by Torah learning, according to Jordan Gorfinkel, 51, the entertainment entrepreneur who managed the Batman franchise for a decade before creating his own Avalanche Comics Entertainment company.

In the sanctuary of Tifereth Israel Synagogue on Wednesday night, April 10, Gorfinkel likened the Superman character created in the 1930s by Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster to the concept that children have about the heroes in the Torah: “They are heroic and flawless. Abraham and Sarah are wise and all powerful. They find the first true God. They begin monotheism. … They seem invulnerable.”

However, as people grow older and their knowledge deepens, they discover that “the Torah does not hold back about these historical figures. The Torah shows them warts and all,” Gorfinkel said. “So, for example, you have the story of Abraham and Sarah debating what are we going to do about Ishmael, and Sarah says send him away, and Abraham doesn’t want to. That is a really powerful story. … Is that all that much different from the types of dilemmas that characters like Spiderman, The Hulk, and Captain America, and so forth, have?” Those characters were created by Stan Lee during the 1940s through the 1960s.

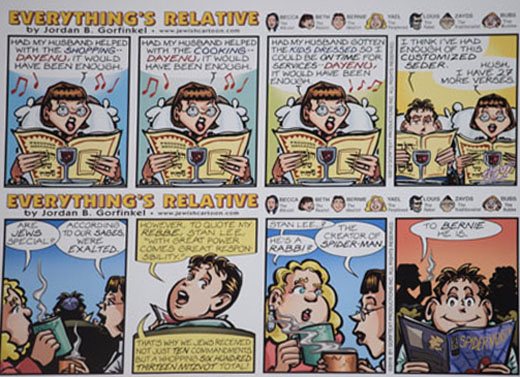

Gorfinkel, a Shomer Shabbos Jew who also draws a weekly “Everything’s Relative” column about Jewish life, delved into the careers of Shuster and Siegel and that of Lee to explain how the American Jewish experience was an important factor in the evolution of comic books and graphic novels.

With Passover approaching, and Gorfinkel’s own Passover Haggadah Graphic Novel now on sale for $20, the cartoonist and story teller began his lecture with a comparison between the stories of Moses and Superman. He said both tales involve “a doomed society. That society had a couple of parents who wanted to save a remnant of their family, so they took their beloved child and sent that child away just as their civilization was on the brink of apocalypse. That child traveled a long distance and was adopted by kindly people who raised this child without any knowledge of who this child was until this child grew up and realized the incredible power within him and physically, so that he would become the champion of his people and the savior, indeed the beacon of light, for humanity for all time.”

That Shuster and Siegel would draw upon such a theme was not surprising, given the times and circumstances in which they were living, Gorfinkel said. “Siegel and Shuster were two teenagers living in the Glenville section of Cleveland, Ohio. They were going to public school. They were the children of immigrants and they wanted more than anything to fulfill the same aspirations that all kids want, and that is, of course, to be like everyone else, basically to assimilate.”

However, there were obstacles. Their parents spoke with accents. The girl on whom they had a crush – and upon whom the character of Lois Lane was modeled – failed to appreciate them. “They posited that if only Lois could see what the stooped mild-mannered teenagers who were intellectual but not necessarily very athletically inclined were really like – that if they stand tall and pull open their shirt and underneath the tzitzit is a big S, and they are in fact a Superman, they would be accepted.”

However, that was after the Superman idea evolved. As initially conceptualized, the villain in their comic strip was going to be a character called Ubermensch (German for Superman). It was 1935, World War II was approaching, and Siegel (the writer) and Shuster (the illustrator) were familiar with nazism, fascism, and totalitarianism. “They knew about the evil that was being foisted, not only upon their own people but upon the world at large, and it never would have occurred to them that the Ubermensch could be anything other than a villain because that was the ideal of the Nazis and that was the thing that they (Shuster and Siegel) would like to vanquish.” However, an editor for DC comics, suggested that the comic would be more successful if they turned the villain into a hero, “and like good talmidim, Siegel and Shuster, listened to their rebbe and they changed the Ubermensch into Superman.”

The United States government in a sense adopted Superman, distributing millions of the comic books during World War II to boost the morale of GIs at home and overseas. As one might imagine, the U.S. government wanted stories that were patriotic and that made Superman all-powerful and God-like, with his enemies portrayed as evil incarnate.

After the war, Stanley Lieber adopted the pen name Stan Lee (or his “nom-de-comic,” according to Gorfinkel) because he wanted to save his real name for the great American novel that he never got to write. Stan Lee was a bit like Rabbi Akiva, in Gorfinkel’s estimate, because he began anew at age 40 when he transformed Timely Comics, his wife’s cousin’s company, into Marvel Comics. Rabbi Akiva only began to study Torah at the same age.

In contrast to Siegel and Shuster, Lee was raised not as the child of immigrants, but on the upper West Side of Manhattan in the mainstream of the American experience. “It is fascinating to me that he developed a more finely tuned sense of how to apply Judaism to the medium of comics and graphic novels,” Gorfinkel said. “He posited that the adventure and physical fisticuffs were important, but the real center of the stories would be inner conflict. ‘Oh my gosh what have I done?’ ‘What am I?’ or ‘If only I had stopped that bad guy earlier, my Uncle Ben might be alive today’ or … ‘Mary Jane is heads and shoulder above me; how am I going to make her my girlfriend?’ That is the stuff the drew us.”

Gorfinkel said that as an editor for the Batman franchise he worked on more than 2,000 stories about the character (also known as “The Dark Knight”) featured in comics,graphic novels, TV shows, movies, games, T-shirts, and rides. He said he always kept Shabbat, leaving work early on Friday afternoons in order to be home before nightfall, and that no one at DC Comics ever complained. Perhaps that was because his ideas over the years helped to earn the parent company, Warner Brothers, a fortune. “If you’ve seen The Dark Knight Rises, the third in the Christopher Nolan trilogy of movies, you see work that was inspired my ideas,” Gorfinkel said. Additionally, he said, his work inspired the latest season of Arrow on CW and the entire season of Gotham on Fox. Now, having his own company, he is working on a Transformer movie.

His Passover Haggadah Graphic Novel is another example in the cycle of Judaism influencing cartoonists and cartoonists influencing Judaism, Gorfinkel said. Unlike illuminated Haggadot in which there are illustrations, but which seem to be separate from the story, this Haggadah doesn’t narrate the Passover story, it shows the story unfolding.

Gorfinkel said the Passover Haggadah Graphic Novel was mostly illustrated by Israeli artist Erez Zadok, who because he lives in the historic homeland of the Jewish people is familiar with both the traditional Pesach stories and modern applications. Living and breathing the religious atmosphere, “it is in his kishkes,” Gorfinkel suggested. For this project, Gorfinkel resumed his role as a creator and editor, although he did offer a side set of cartoons involving a little goat guide. (Chad Gadya).

In a variant on the Four Questions asked by the Youngest Son at a Passover Seder, the cartoonist invited four youngsters to the front of the sanctuary and asked each of them about the creative process that a comic book goes through. Elijah and Levi Sklar, 10 and 7, and Ari and Jacob Oren-Winkler, 8 and 10, had attended a workshop earlier in the day that Gorfinkel had conducted for the synagogue’s Torah School students, so they were primed with answers. What is the first step? Write the script, said Elijah. Second? Draw the pictures with a blue pencil, said Levi. Third? Trace over the blue pencil drawing with ink, said Ari. (The blue pencil does not show up in the photographic process.) Fourth? Add the lettering, concluded Jacob.

“Yasher Koach!” applauded educator Yiftach Levy from the audience.

Republished from San Diego Jewish World