Although Ruth Goldschmiedova Sax of Chula Vista conceded that she didn’t grow up with comics, or even know about Superman, whom she subsequently came to admire, she was clearly the hit of a panel on art and the Holocaust that was held Thursday, July 19, at the Comic-Can convention. The reason, as some attendees expressed out loud even before the program began: “How often will we get to meet a Holocaust survivor in person?”

Sax, 90, survived internment in three Holocaust camps – Theresienstadt, Oederan, and Auschwitz – and according to her daughter and fellow panelist, Sandra Scheller, she was forced to stand naked before the Auschwitz doctor Josef Mengele six times as he decided whether she should continue to live or be sent to the gas chambers. “I’m sitting next to a super-hero without a cape,” Scheller declared to general applause from the audience. Scheller authored her mother’s memoir, Try to Remember, Never Forget.

Sax won the hearts of her audience when she reflected humorously about her life, saying in some ways it had changed dramatically, from Holocaust camp to Comic-Con, but in others it hadn’t changed at all. As a slide was projected of her as a one-year-old child, she quipped, “I was pushed in a baby carriage, and now I’m being pushed in a wheel chair.”

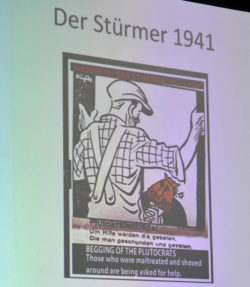

She said she recalled how shocked and scandalized she was, even at the age of 11, by Nazi art works that dehumanized Jews. As an example, a slide was projected of a cartoon that appeared in Der Sturmer, a Nazi publication, in which there was a vile caricature of a Jew begging a German whom he once used to bully to now give him help. She said that before she was sent to the Nazi camps she had thought that she might become an artist; perhaps even a fashion designer, but if she had drawn what she had seen in the camps and had been caught, she would have been put to death. In one of the camps where she was interned, Oederan, she was forced to make ammunition for the German war machine, a product she believes she helped sabotage by scratching the bullets with sand.

After the war, she married Kurt Sax, with whom she celebrated a 63rd wedding anniversary before his death. Kurt and Ruth moved to the United States, “the land of Superman,” Ruth said. “Maybe if I had known about Superman I might have had more faith that I would be free one day. It had taken longer than I thought.”

Before turning the microphone over to other panelists, Ruth Sax dispatched Adolf Hitler and the Nazis in this fashion: “God created such a beautiful world, only some people make it so miserable.” She also commented, “Some of the propaganda is difficult to see at times, but I am here now, in this country, and I can say, ‘This is part of my past.’”

Author Igor Goldkind, whose latest book, which touches on the Holocaust, is titled Is She Available, reminded the audience in the well-attended panel session that the Superman character had been created before World War II by two Jews from Cleveland, Jerry Siegel and Joe Schuster. Other superheroes like Captain America, as well as most of the Marvel universe of super heroes also were created by Jews, Stan Lee being notable among them.

Sandra Scheller reviewed other artists of the Holocaust, starting with her cousin Kitty Brunerova, whose drawing of butterflies at the Theresienstadt ghetto and concentration camp has been placed on commemorative stamp by Czechoslovakia. Her talent did not save her; she was sent from Theresienstadt (known as Terezin in the Czech language) to Auschwitz, where she was murdered. Another artist, who had been a teacher to Ruth Sax, was Otto Ungar, whose representations of Theresienstadt were so graphic that the Nazis cut off his fingers as punishment, then transported him to Auschwitz to be murdered. Another artist of the era was Dina Babbitt, who drew Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs on a back wall of the children’s barracks. Condemned with her mother to go to the gas chamber, she was saved when Mengele decided he needed someone to portray his work. Babbitt reportedly told Mengele that as long as her mother was in line for the gas chamber, they would die together. Instead, Mengele had both of them returned to their barracks.

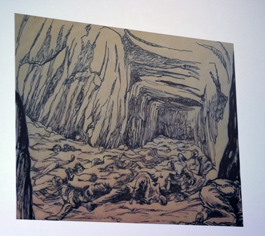

Scheller completed her presentation by screening some drawings that Allied soldiers made at the end of the war, of the scenes they encountered in a cave where the Nazis had taken 336 prisoners and, in retaliation for the killing of some German policemen, shot each one of them in the back of the head.

Esther Finder, founder of Generations of the Shoah – Nevada, an organization of children and grandchildren of Holocaust survivors, sketched the times in which Siegel and Schuster developed the Superman character. The Nazis believed in social Darwinism, in which the fittest human beings were destined to rule over those who were considered underhumans, among them Jews, Slavs and Africans. This idea in large part was built upon American eugenics studies. Anti-Semitism was present not only in Germany but also in the United States, where “American Jews were discriminated against and were painfully aware that in order to get ahead they had to change their names and hide their ethnicity.”

The American Superman character was the reverse of the Nazi Superman, while the Nazi superman was immoral and a bully, who would trample others; the American Superman “represented strength, morality, justice both legal and social, and the belief that everything would work out right,” according to Finder. In the 1950s Superman television series, that motto became “truth, justice and the American way.”

The Jewish origins of Superman can be seen by comparing his origin story to that of Moses in the Bible, Finder said. “Moses survived because his mother put him in a vessel and sent him down the river…set adrift in the hope that someone would find Moses and care for him.” In the Superman mythology, added Finder, a former psychology professor at Montgomery University in Maryland, Kal-El was imperiled, put in a vessel, sent to earth where it was hoped someone would find him and take care of him.” She noted that the “El” in “Kal-El” is one of the Hebrew names for God. He did godly work: “America’s Superman was moral, kind, sensitive… He could easily destroy but his powers were used for good…. He was mild-mannered except when he had to fight to save people.”

The final panelist, Robert Scott, the Jewish owner of ComicKaze book store, said it was no coincidence that people from struggling Jewish families gave the world its super heroes. “Joe Schuster’s parents couldn’t afford paper. He would go from store to store to get paper” and even drew on unused wall paper. Scott said comic books are a democratic medium; all anyone needs is “the ability to tell your story, unedited, unaltered, and put it out there for anyone else.”

I had an opportunity to pose a question to the panel, based on my interview the day before with comic book artist Miriam Libicki, whose Holocaust comic book, Ruchie’s Job, contains enough humor that she was worried some readers might be offended. Some people believe there was nothing funny about the Holocaust.

The panelists had reassuring words for Libicki. “Gallows humor is what people do, to try to make sense” of their situations, said Goldkind.

Scheller said in combatting the despair of the Holocaust, “we tried many medicines; The ones that worked the most were humor and hope.”

And Sax said that on Friday nights in the concentration camp, she and other girls of her age (about 15) used to climb up onto the third bunk, and pretend that they were back in their kitchens cooking. They’d laugh about their favorite meals, which in Sax’s case was sauerkraut and dumplings!

Republished from San Diego Jewish World