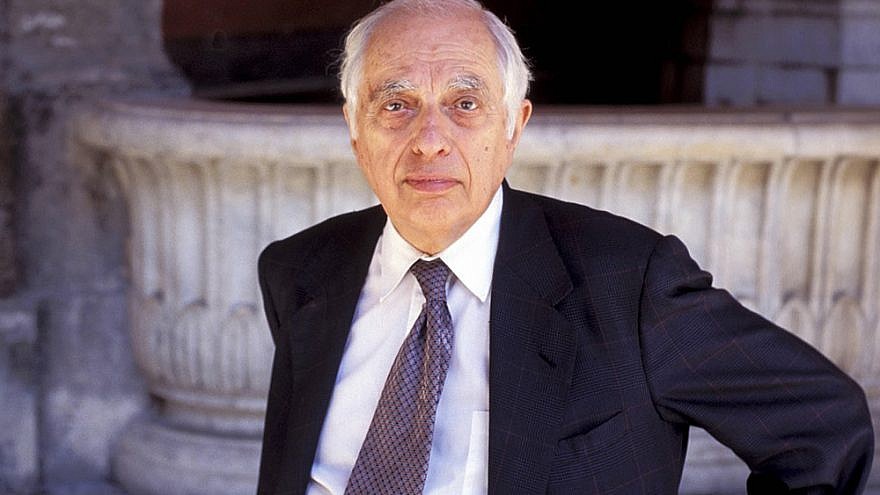

When the American monthly magazine Commentary published the Princeton University professor’s article titled “The Return of Islam” in January 1976, its readers were shocked: His essay foresaw—before the Islamic revolution and the reign of the ayatollahs began in Iran, and when Osama bin Laden was still just a young Sunni extremist—that Islam would soon overturn the tables. And it issued a warning. Author Bernard Lewis explained to us that which we still hadn’t come to grasp—namely, the totalitarian intentions of the Ayatollah Khomeini, who in those days was simply an exiled cleric in France while the Shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, firmly sat on the throne. With his characteristic English “understatement,” Lewis explained: “It was easy to understand what the ayatollah would do by reading his texts, but few knew Farsi.”

Lewis knew and spoke at least a dozen languages, including Arabic and Turkish, and was fully versed in their subtle nuances. It was an ability he used with an ironic elegance and a tinge of pride whenever he cited texts unknown by most, minimizing his accent that nevertheless remained British even after he became a naturalized citizen of the United States in 1982.

Was he, in fact, a “Westernist”? It can be said that he was a lover of historical analysis; he was very troubled by any forms of extremism, fettering it also among his friends. Even in his manners he was a master of style, as well as clever and witty. By my invitation, he came to Italy many times to explain an unknown universe. The world at its highest levels consulted him; I remember several limousines that came to the United States to take him to take him to the White House and its environs. He loved Israel, where he spent every year for at least a couple of months, and he deeply cared and worried about it.

He loved the West, particularly democracy, but gracefully, without publicly advocating or thinking that Muslim nations could adopt its system. Lewis was deeply convinced that the study of culture helps understand not only the past, but the future as well, and passed this idea to his closest students, among them to his friend and scholar (almost like a son) Harold Rhode.

From the time Lewis was drafted as an intelligence officer in the British army during the 1940s, he toured the Middle East working in MI6, becoming a young “Lawrence of Arabia” fascinated by the Islamic world. When, still a child, he prepared for his bar mitzvah in London, he learned to read his biblical portion in Hebrew, and from there ventured into the field of Semitic languages, which he passionately studied his entire life. He viewed the Middle East as a humanist; he talked about everything connected to it, including poetry, cities, dress, literature, arms, anti-Semitism, women, role models, leaders, etc. How fortunate were his students in the institutions and out of them, including myself, to meet him, to appreciate him, and to be enlightened by his incredible knowledge and charm.

I met him the first time in Bologna in 1991, when the Italian publishing house Il Mulino invited me to hear him read from his latest book. I immediately interviewed him. I must admit that at the time, I didn’t comprehend the depth of what he said, but nonetheless sensed its importance, and so kept reading his works. Later in Israel, I popped up uninvited at his hospital room when I learned that he had undergone an operation. Upon waking up, he found both me and Israeli military official Uri Lubrani, at the time charged with the Israel Defense Forces’ activities in Lebanon and himself a major expert on Muslim culture. Since then, I have had the great pleasure of listening to his stories and interpretations, asking him every possible question. He gifted me with his answers during long walks along Tel Aviv’s promenade, often in the company of his life partner and co-author, Buntzie Ellis Churchill.

Bernard Lewis is now gone, but he left a compact group that will at least try to keep his flag high. There is a group of people he has put together, thought with, visited at home, admitted at his table and at his studio. We all met 12 years ago for his 90th birthday at the Bellevue Stratford Hotel in Philadelphia (famous for hosting Tsar Nicholas II), convening to partake in a conference that notable leaders, scholars, journalists and activists attended. Among them were Sufi Muslim leader Muhammad Hisham Kabbani, former U.S. Vice President Dick Cheney, the late great Lebanese-American historian Fouad Ajami, the Somali-Dutch human-rights heroine Ayaan Hirsi Ali, former U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger . . . and us, his students, who received a T-shirt emblazoned with a photo of Bernard Lewis on the front.

There, we discussed the magnitude of a culture that has given strength and dignity to many millions of people, but that—and I quote Lewis here, “is a religion of power, and in the Muslim world view it is right and proper that power should be wielded by Muslims and Muslims alone. Others may receive the tolerance, even the benevolence, of the Muslim state, provided that they clearly recognize Muslim supremacy. That non-Muslims should rule over Muslims is an offense against the laws of God […] Islam is not conceived as a religion in the limited Western sense but as a community, a loyalty, and a way of life … ”

Recently, Bernard and I spoke via Skype with the help of our mutual friend, Harold Rhode; he wanted to know where I was, how I was, etc. His affectionate manner was on par with his culture, even if, at the end, his strength was waning.

He continued to speak to all those who wanted to understand the Middle East, and he will carry on doing so through his writings, and with his voice inscribed in our memory and, most of all, in our hearts.

Journalist Fiamma Nirenstein was a member of the Italian Parliament (2008-13), where she served as vice president of the Committee on Foreign Affairs in the Chamber of Deputies, served in the Council of Europe in Strasbourg, and established and chaired the Committee for the Inquiry Into Anti-Semitism. A founding member of the international Friends of Israel Initiative, she has written 13 books, including “Israel Is Us” (2009). Currently, she is a fellow at the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs.

Translation by Amy Rosenthal.