Growing up in a small English town that offered refuge for my parents in their flight from the Nazis, I was acutely aware of many differences between my own family and those of my friends.

The preoccupation with events on “the Continent”; the energy spent recreating a semblance of the Jewish life they had left behind; the effort to try and assimilate into British Jewry; the struggle to get rid of accents and the relief of falling back into German at home and with friends—all added up to that classic Jewish rootlessness and the feeling of being tossed about on the waves of history.

But none of these held as much significance as the one structural deficiency in our family—the absence of any grandparents.

There were few stories of my grandparents. All I knew of them were the large, sepia-brown 3-D photos of two dignified elderly people that took pride of place on the mantelpiece, until sometime in the early 1970s when, brittle with age, the photo of my paternal grandmother finally peeled away from its backing, leaving only a wooden silhouette of her form.

The fate of my father’s parents was sealed in the early years of the Shoah when the Nazis sent all the residents of the Jewish retirement home where they lived to be murdered at Auschwitz. From the last photo of them, my grandparents look to be in their late 60s or early 70s.

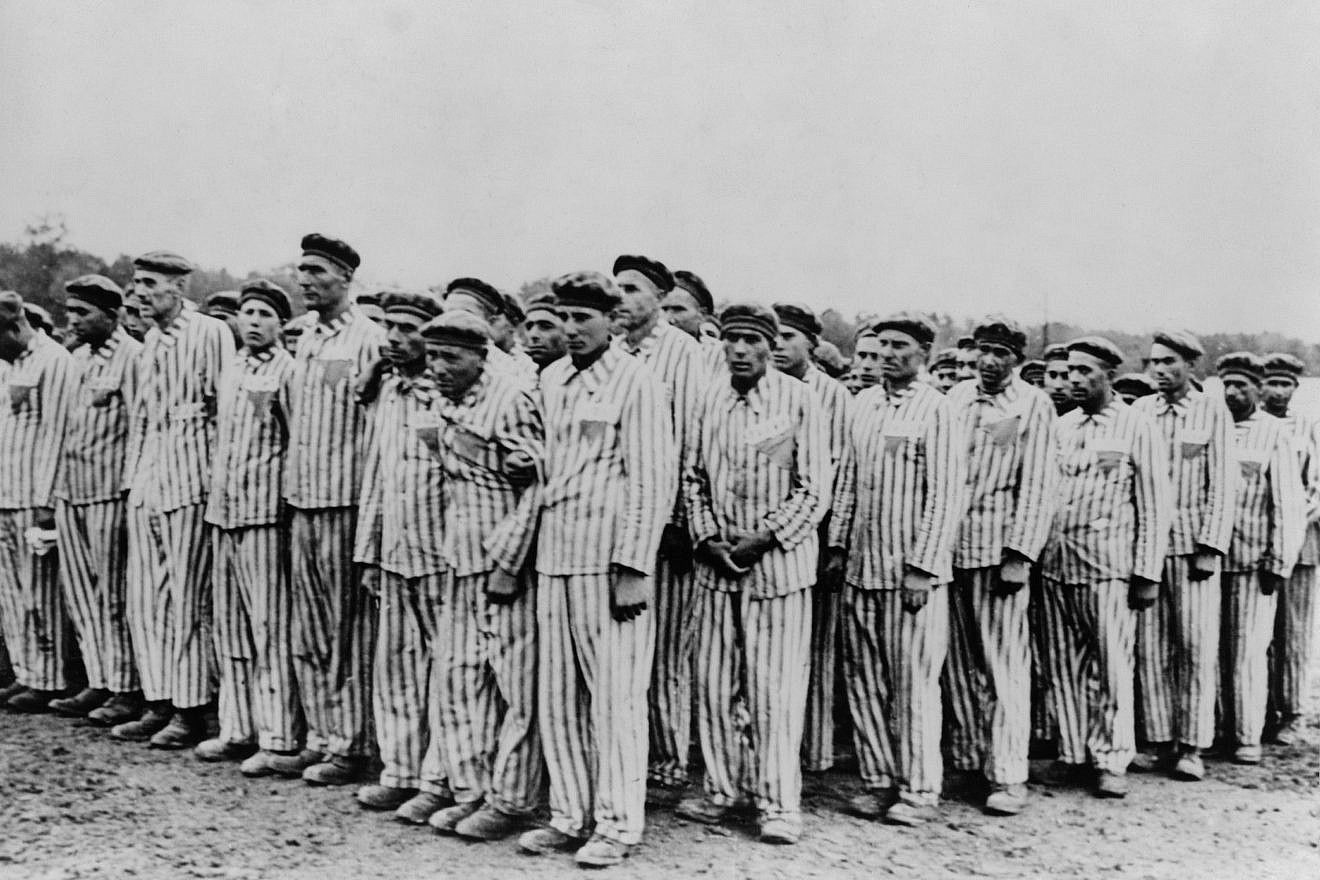

My mother and father each dealt in their own way with sharing pieces of information about their parents or their own experiences. When pressed to talk about the war, my father preferred to joke about his stint as a private in the British Home Guard rather than tell us much about his time in Buchenwald after his arrest on Kristallnacht in November 1938.

Since he knew with certainty what had befallen his parents and when, it was as if he could pinpoint that date and recount their past up to that time. I knew all about my grandfather’s kosher butcher shop. And my grandmother’s business acumen and her ability to mediate tensions among the extended family were legendary.

Tales of their life were usually recounted quite willingly by my father, often with humor. Perhaps it was because they had already reached a relatively old age when they were killed or maybe it was precisely to avenge the meaninglessness of their deaths that he forced himself to focus with joy on the minutiae of their pre-war lives.

My mother’s parents, Polish Jews who had lived in Leipzig as stateless persons since the early 1920s, were in their early 50s at the outbreak of the Second World War.

After my mother was able to arrange my father’s release from Buchenwald, a hurried Jewish wedding took place in Leipzig, and then, under separate steerage, my parents left to begin new lives in England in the spring of 1939.

My mother and her two sisters were able to enter England by agreeing to work as “domestics” or maids, and her two younger brothers were sent on the Kindertransport. My mother was lucky enough to be employed by a Jewish family in the north of England, but the only place my father could find a job was in London, so they spent their first year of married life apart.

The complete inability of Jews to obtain entry to any Western country meant enforced separation for many Jewish families, and for many of those fortunate or creative enough to get visas, it took years to shake off the guilt for those they left behind.

So it was that the depth of my mother’s sorrow became one of my earliest memories. On an otherwise unremarkable vacation to Amsterdam one summer in the early 1960s, my father decided that we should visit the Anne Frank House.

As my mother stepped across the threshold of the house that had sheltered the Frank family less than 20 years before, she became hysterical and broke down weeping. As l replay the incident in my mind, I hear her screaming the names of dead relatives and cursing the Germans, but after the lapse of more than five decades, I am no longer sure if it is a true memory or my imagining how she would have reacted.

At the time, from my child-like perspective, all the events of World War II and the Holocaust seemed to have happened in ancient history. Now, of course, I realize how raw it must have been for my parents. My brother was born just nine years after my parents saw their parents for the last time. My entry into the world came only seven years after my mother received the impersonal postcard from the International Red Cross informing her of the fact that her parents had “most likely” perished in Auschwitz after having fled to Belgium and France in front of the Nazis.

An affirmation of their existence

I made my first visit to Israel as a teenager in 1968. On several occasions before I made aliyah in the 1990s, I made a point of visiting the Hall of Names at Yad Vashem in Jerusalem. There, I perused the names of some of the more than 2 million victims of the Holocaust recorded at the time on an aging microfiche system.

Like any database, the Hall of Names is only as good as its input. Beginning shortly after Yad Vashem was created in the 1950s, a call went out via Jewish newspapers and landsmanschaften throughout the world for survivors to complete questionnaires with as much information as possible about their murdered relatives.

I remember watching my father filling out the questionnaire about his murdered relatives in the l960s. It was always reassuring in an odd kind of way to make the pilgrimage to the Hall of Names whenever I was in Israel, just to touch the pieces of paper that along with photographs, were the only tangible evidence of the fact that I had grandparents.

Just to pronounce their names out loud as I asked for the forms was somehow an affirmation of their existence.

The deprival of family continuity that has impacted three generations of survivors and their families is perhaps one of the most enduring crimes of the Nazis.

All of this comes to mind as we approach International Holocaust Remembrance Day, which marks the 79th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau on Jan. 27.

This year, the day will be marked on Friday, Jan. 26 at the U.N. General Assembly Hall in New York. U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres will join Holocaust survivors and Israeli officials at the ceremony. Yes, the same Guterres who stated that the Oct. 7 mass-murder rampage by Hamas terrorists in southern Israel “did not take place in a vacuum.”

The same Guterres whose agency took three months to send its emissary on sexual violence in conflict to Israel to investigate Hamas’s crimes of rape and bestiality.

The same United Nations whose subsidiary program, the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA), uses an educational curriculum that has indoctrinated children in Gaza with hatred against Israel for decades and employs teachers who applauded the Hamas attacks.

Israelis who have lived through the past months since Oct. 7 are bereft, grieving and incredulous that so many international bodies refuse to recognize the suffering brought on by Hamas.

No ceremony or pious words on International Holocaust Remembrance Day will wipe away that sense of betrayal.

This is one year that I won’t be marking that day of distant liberation from Nazi brutality. Instead, I’ll be waiting for the day when we can finally commemorate our liberation from Islamist terror.