A photo of the U.S. Ambassador to Israel David Friedman and U.S. envoy Jason Greenblatt on July 1 striking a thin, symbolic wall with a sledgehammer—a wall built to separate two parts of the ancient Pilgrimage Road—became the headline of the archaeological site’s inauguration ceremony.

The road is one of the most sensational archaeological discoveries to be made in Jerusalem since Israel’s establishment. On this road, which was remarkably preserved under the ashes of the Roman destruction, many thousands of Jews, according to the historical descriptions, walked to the Temple Mount in Second Temple times, after a ritual bath in the nearby Siloam Pool.

Friedman attended the dedication ceremony not only to express recognition of Israeli sovereignty over the City of David area, but also to admire a magnificent archaeological endeavor of the Israel Antiquities Authority, replete with discoveries. Although this site was dedicated by Israel on June 30, the project began more than a hundred years ago, at an excavation by non-Israeli archaeologists, at a time when the State of Israel did not exist and Jerusalem was under Muslim rule.

Archaeologists from the Israel Antiquities Authority, closely supervised by safety engineers (in line with the world’s strictest standards), have been searching for or excavating the Pilgrimage Road, mistakenly known as the Herodian Road, only since the beginning of the 2000s. But they and the Antiquities Authority are not the first to look for this road or excavate it.

They were preceded in the period of Jordanian rule by the British archaeologist Kathleen Kenyon, who uncovered the more northern parts of the Pilgrimage Road and also warned that the City of David should be excavated hastily, before the Jordanians paved a road there—which is indeed what they eventually did. Kenyon was preceded by an archaeological research delegation during the period of the British Mandate. And this delegation was preceded at the end of the nineteenth century, in the time of Ottoman rule, by the archaeologists Jones Bliss and Archibald Dickie.

Before discussing the many discoveries from the new excavation, we first need to disprove the allegation that it endangers the homes of the residents of the Arab neighborhood of Silwan.

Local Arabs took part in the digs … until they were threatened

Over the years, hundreds of Silwan residents took part in the archaeological digs of the Antiquities Authority funded by the NGO “Elad” (the name is a Hebrew acronym for “To the City of David”). More than once the digging was done below the houses of these same Arab workers. They would have kept working there to this very day had they not been threatened with violence by emissaries of Hamas and the Palestinian Authority in eastern Jerusalem.

Political opponents of the archaeological excavations in the City of David, which have been conducted for almost 50 years, try every few years to impede the work of the Antiquities Authority, often resorting to legal proceedings. Once or twice they have even gotten as far as the Supreme Court, whose justices are known to be particularly sensitive to claims of infringement of human rights. The petitioners claimed that the excavations endangered the residents of Silwan, and the court looked into their allegations and rejected them.

Former Supreme Court Justice Edna Arbel, responding to a petition submitted against the excavations in the Givati Parking Lot (part of the City of David) (High Court of Justice file 9252/080), stated that “many of the claims made by the petitioners were mere empty words, with no basis presented for these claims.” After Israeli professionals described to her a series of operations undertaken to ensure the stability of the residential dwellings in the area, she said, “The petitioners did not present any evidence that would substantiate a connection between the excavations and the damages that were allegedly caused to their homes.”

Justice Arbel continued:

“There appears to be no disagreement that the parking lot is within the territory of a national park and that the excavations conducted in it so far have yielded an impressive archaeological trove, which is of great scientific and historical importance that transcends Israel’s borders. … Israel’s rich historical past is enfolded layer by layer in its soil. The historical annals of the land, of the peoples who have lived in it, passed through it, and entered the pages of history. Over the years, these annals were buried in the land and became its secrets.”

“Israel,” the justice is quoted as saying in another court ruling, “is indeed a young country, but its roots are deep in human history, and its land is replete in its length and breadth with ancient relics of an ancient human civilization, which lived and created in this region for thousands of years. This is all the more so regarding the locale known as the City of David. The remains of the City of David tell the annals of Jerusalem for thousands of years, as one can still learn about them from the Hebrew Bible (see, for example, Samuel II, 4:8, 9:11; Chronicles I, 15:1; and the place itself is mentioned even earlier, of course, in the story of the binding of Isaac) and other sources.

“The importance of the secrets of the City of David, national and international, is not unique to the Jewish people, but rather is of importance to anyone who wants to delve into the history of this region, which is the cradle of the monotheistic religions. The importance of the archaeological research lies not only in understanding the past of the country and in the possibility of verifying the truth of the details known to us from other sources, but also in the fact that it sheds light on the development of human culture. As such, its importance transcends peoples and borders.”

“It had been made clear,” Arbel noted, “that the excavation work in the parking lot was being done under the supervision and accompaniment [of] professionals.”

Seals, palaces and a golden bell

And indeed, some years later the Givati Parking Lot provided a rich trove of instructive archaeological findings. The chief finding is an impressive structure from the end of the Second Temple period which, in the view of some archaeologists, served Queen Helena of the kingdom of Adiabene in Assyria about 2,000 years ago. Helena converted to Judaism and built magnificent palaces in the City of David. (The palaces of the kings of Adiabene are mentioned in the writings of Josephus, and they were reconstructed at the Israel Museum in the Jerusalem Model of the end of the Second Temple period.)

Also found in the Givati Parking Lot were relics of First Temple days: a six-meter-wide Byzantine road, of which 30 meters were uncovered; a structure of an estate owner from the Roman period with a courtyard, garden, and mikvah [Jewish ritual bath]; and remnants of the ancient Muslim period. An especially interesting find was a stamp seal on which, in ancient Hebrew script, can be seen the words: “For Natanmelech eved hamelech [‘slave of the king’].” The name Natanmelech appears in Kings II, and the researchers say the archaeological finding is dated from the same period as the biblical account—the second half of the seventh century BCE.

According to the researchers, the parking lot is apparently also the location of the ancient Acra fortress, which was built by King Antiochus Epiphanes in 167 BCE during the period of Seleucid rule in the Land of Israel. The fortress remained a stronghold of the Seleucids and their Hellenized supporters during the Maccabean Revolt.

Another ruling by Arbel dealt with the Herodian drainage tunnel located right under the route of the Pilgrimage Road (also known as the “Herodian Street”). The drainage tunnel was discovered a few years ago by archaeologists Ronny Reich and Eli Shukrun, and today one can walk through it from the vicinity of the Siloam Pool to the foundations of the Western Wall (in the vicinity of the Davidson Center).

Exciting findings were made in this drainage tunnel, such as cooking pots and kitchenware with which the rebels ate their last meals before the Romans discovered them and killed about 2,000 of them (according to Josephus). Also found in the drainage tunnel was a sword that belonged to a Roman legionnaire, still in its leather scabbard, and a picture of the Temple menorah that was scratched on the back of a broken potsherd by an anonymous individual who, apparently, had seen the real menorah with his own eyes.

In addition, an intriguing, one-of-a-kind artifact was found in the drainage tunnel: a gold bell with a loop at its edge. This bell had been sewn onto the hem of a garment of a distinguished man of Jerusalem, possibly even the High Priest himself. (Exodus 39:24-26.)

Found on the floor of the drainage tunnel was the cover of a cistern from First Temple days. The cistern is located half under the drainage tunnel and half (this part is blocked and inaccessible) on the Temple Mount. Here, too, some kitchenware was found, and Jewish rebels against the Romans may have spent their last moments hiding in this cistern as well.

‘The infringement of the property rights, to the extent it exists, is minor’

It was also claimed to the Supreme Court (file 1308/08) regarding the drainage tunnel that the work performed in it endangered the Silwan residents just above it. Here, too, in an additional and separate ruling, Justice Arbel declared:

“First, notwithstanding the claims of the petitioners, it was explained that the work is being done under professional engineering supervision and as part of an approved construction plan. And not only that, as is clear from the statements of the respondents, most of the operations that the Antiquities Authority is carrying out in the drainage canal are not actual excavation work but involve clearing out garbage that has accumulated in the canal for about two thousand years.”

The justice mentioned the reinforcement work being done to prevent damage and added:

“One may say, therefore, that the work is performed with the accompaniment and supervision of professionals, not as the petitioners claim, and it is clear that these professionals are not only concerned about the completion of the work in the drainage channel, but also are aware of their obligation to make sure the work is done in a way that will not harm the petitioners, their family members, or their property.”

As for the petitioners’ right to ownership of the ground beneath their homes, the justice stated:

“To the extent that such an infringement indeed exists, it is minor. … Against the infringement stands a significant public interest in carrying out the work. Indeed, the unveiling of the secrets of the past, which lay for hundreds and thousands of years in the bowels of the earth, is a central aspect of archaeological research. The performance of this research is a many-faceted public interest, whether because of the contribution it makes to understanding the history of the country and the history of the Jewish people, or because of the contribution it makes to understanding historical events that are of importance not solely to the Jewish people and to their history.”

The Givati Parking Lot and the drainage tunnel are only two examples of sites in the City of David that in recent years have disclosed secrets to us. There are other important examples: In 2005, archaeologist Dr. Eilat Mazar discovered remnants of a large stone structure which she is inclined to identify as the palace of King David.

In the 1970s and 1980s, archaeologist Dr. Yigal Shiloh discovered the Bullae House and the Ahiel House within the area of excavations in the City of David called Area G. On the bullae found in the excavation area, names such as Shiftiyahu Ben Tsafen or Beniyahu Ben Hoshiyo had survived, as well as the names Yirmeyahu Ben Shafan (a royal scribe) and Azaryahu Ben Hilkiyahu (a priest from First Temple Days). Forty-five bullae out of the 51 found in the Bullae House bore inscriptions in ancient Hebrew writing and included the name of the owner of the seal along with the name of his father.

As the 2000s were approaching, fortifications were discovered in the City of David for a spring and a Canaanite pool. A large pool, quarried in the natural rock, it was a mainstay of the water system from which the Canaanites drew their water. This pool was quarried in the eighteenth century BCE but went out of use completely in the eighth century BCE, possibly because of the excavation of the famous Hezekiah Aqueduct.

The Pilgrimage Road

And now the Pilgrimage Road has been discovered. Only about 350 of the 700-meter road have been uncovered so far. Although the prevailing opinion was that Herod built the road, it turns out it was built in the time of the Roman governors who came after him, specifically in the days of the Roman governor Pontius Pilate.

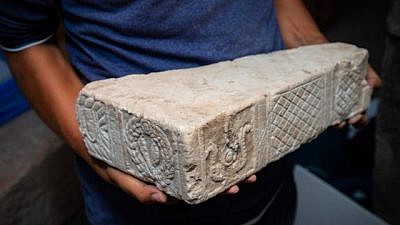

The archaeologists who have been excavating the Pilgrimage Road over the past five years—Dr. Joe Uziel, Ari Levi, Nachshon Zenton and Moran Hajibi—have also shattered another assumption: It was not the poor who lived along the Pilgrimage Road in the area of the “Lower City,” but in fact a wealthy population. Among the ravages of destruction that have been uncovered along the road, luxury items have been found, including inlaid stone tables, jewelry of various kinds, and perfume bottles.

Along with these are many other findings: coins, cooking pots, complete stone and clay tools, rare glass items, a magnificent dais (for public announcements) and parts of arrows and catapults—testimony to the last battle in the “Eastern Hill” during the Great Revolt of the Jews against the Romans, which concluded with the destruction of the Second Temple.

From Warren to Kenyon: The archaeologists who excavated the City of David

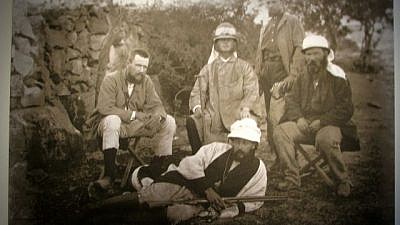

The many discoveries in the City of David during the period of Israeli rule join dozens of excavations and excavators who have dug in the City of David, the most archaeologically excavated and researched site in Jerusalem during the years of modern research. Here, for those who speak of Israel conducting a “political excavation,” is a list of the excavators of the City of David whose work preceded the State of Israel:

In the period of Ottoman rule, Charles Warren of the Palestine Exploration Fund excavated extensively in Jerusalem and discovered the water system known as Warren’s Shaft (1867).

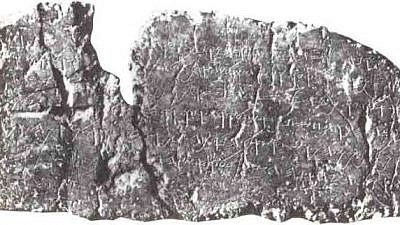

In 1880, two teenage boys alerted the German architect Conrad Schick to the existence of an ancient inscription engraved beside the southern outlet of the water tunnel in the City of David. This discovery of the Siloam inscription was among the most important at the site. (The original hangs today in a Turkish museum.)

In 1881, the German archaeologist Hermann Gutte discovered the Byzantine Siloam Pool as segments of walls from different periods. As noted, more than a hundred years ago Bliss and Dickie discovered parts of the Pilgrimage Road. And Father Louis-Hugues Vincent contributed several of his own discoveries to the understanding of the City of David.

Under British rule after World War I, an international project was conducted to investigate the hill of the City of David, under the sponsorship of the Antiquities Department of the British Mandate government. R.A.S. Macalister excavated at the site for the British Palestine Exploration Fund, and R. Weill on behalf of the French. Under Jordanian rule, as noted, only one excavation was conducted in the City of David, under the leadership of the archaeologist Kathleen Kenyon, who received personal permission from King Hussein to dig there.

Conclusion

When Palestinian media cry out that Silwan is in danger, they lie twice: once, because the Israeli excavators and authorities do not move in the City of David without the authorization of safety engineers, and comply with the strictest standards; and a second time, because the City of David, which covers about 15 acres, constitutes about six percent of the territory of Silwan.

When Palestinian leaders and clerics cry out that the excavations in the City of David endanger the Al-Aqsa mosque, they are deliberately lying. The excavations do not extend beyond the wall of the Temple Mount compound. For years, Israel has made sure to excavate around the Mount and not under it. That was the case regarding the Western Wall and along the Southern Wall of the Temple Mount, and the same is true regarding the City of David. Even when the excavation comes close to the wall of the Mount from the south, it never goes beyond it. The visitors who walk on the Pilgrimage Road, or through the “Herodian drainage tunnel,” ascend to the Davidson Center, which is at the foot of the walls of the Mount and not within it.

Hence it appears that, as in the case of the Temple Mount compound, the acrimony and slander concerning the City of David stem in part from the inability of the inciters to deal with the Jewish past of the site, which is adjacent to the heart of Jerusalem—the Temple Mount.

At a time when Palestinians are rewriting the history of Jerusalem—both the Jewish and the Muslim history—and trying to prove that they were in the city before the Jews (despite what modern research tells us), the City of David is for them another item in their large tapestry of denial of Jewish ties to Jerusalem, its sites and its holy places.

Nadav Shragai is a veteran Israeli journalist.

This article first appeared on the website of the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs.