Relations between Israel and the Vatican have become tense in recent weeks.

In the immediate aftermath of the Oct. 7 Hamas massacre, the Patriarchs and Heads of the Churches in Jerusalem, an ecumenical group of Christian leaders that includes the Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem, Cardinal Pierbattista Pizzaballa, issued a joint statement in which they made no explicit mention of the Hamas atrocities. They included only a vague condemnation of any act that targets civilians.

The Israeli embassy to the Holy See criticized the statement’s “immoral linguistic ambiguity,” which failed to be clear about “what happened, who were the aggressors and who the victims. … It is especially unbelievable that such a sterile document was signed by people of faith.”

This controversy is only the latest in the fraught history of Israel-Vatican relations, which were officially established in Dec. 1993. Besides the Catholic Church’s historical antisemitism, the Vatican was long reluctant to formally recognize Israel for several reasons: Israel did not have internationally recognized borders, the status of Jerusalem and access to its holy sites had not been internationally guaranteed, and Catholics and their institutions were, the Church claimed, not adequately protected under Israeli law.

In addition, the Vatican had concerns about the treatment of Palestinians in the disputed territories and feared that relations with Israel could have negative repercussions for Catholics in Arab countries.

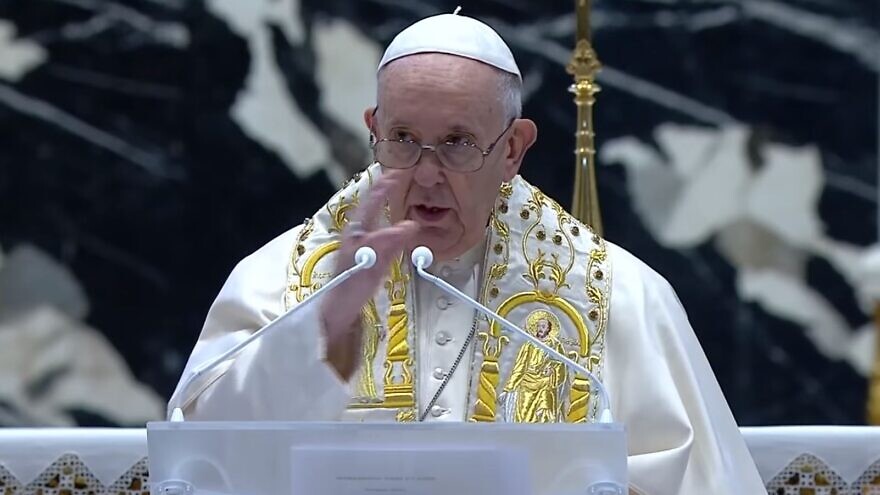

This may explain why, to date, Pope Francis has not labelled Hamas a terrorist organization and has not met with families of Israeli hostages. The latter has not gone unnoticed, especially because the families were received by many leading national figures, including Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni.

According to the Catholic news site Cruxnow, the pontiff’s behavior can be explained as “positioning the Vatican potentially to play a mediating and peace-making role.” In addition, “The bulk of the Christian population in the Holy Land is Arab and Palestinian, so Middle Eastern bishops and clergy tend to be strong supporters of the Palestinian cause.”

Moreover, Cruxnow sees a historic shift underway in terms of the Vatican’s interfaith priorities: “Since the Second Vatican Council in the mid-1960s, Judaism has been the Church’s primordial relationship, unquestionably the highest priority in inter-religious dialogue. Under history’s first pope from the developing world, that’s no longer necessarily the case, as other relationships, especially the dialogue with Islam, have become at least an equally compelling perceived priority.”

Given this, it is not surprising that, since war broke out, Pope Francis has spoken with numerous world leaders, including U.S. President Joe Biden, but there are no reports that Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has been among them.

The larger Catholic world has shown equal ambivalence towards the war. Among Eastern Catholic leaders, the Latin Catholic and Eastern churches in communion with Rome have issued what Israel deems a lukewarm and insufficient condemnations of Hamas. Their first communiqué, issued on Oct. 8, contained a generic statement “against any acts that target civilians, regardless of their nationality.” The next, on Oct. 13, decried the humanitarian situation in Gaza and called for de-escalation. It singled out only Israel in connection with humanitarian issues.

Putting geopolitics aside, Pope Francis’s refusal to firmly condemn Hamas as a terrorist group is a moral failure. If he did so, it would demonstrate a serious commitment to combat antisemitism by action rather than vague ritual condemnations.

This is part of a larger problem. For example, the Vatican has yet to adopt the IHRA definition of antisemitism, which is opposed by many antisemites for including antisemitic tropes targeting Israel. In an interview with the Italian newspaper La Stampa this past May, the American Jewish Committee’s Representative in Italy and Liaison to the Holy See, Lisa Palmieri-Billig, asked Archbishop Paul Richard Gallagher, the Holy See’s Secretary for Relations with States, if it might adopt the IHRA definition in the future. He responded, “The answer is no, there isn’t any possibility. We feel that what comes out of Nostra Aetate and the position of the Popes for many decades now is very clear.”

Nostra Aetate famously condemned the Church’s historic antisemitism and rescinded the charge of deicide. This was commendable, but fossilizing the relationship between Jews and Catholics in a document that is now almost 60 years old does not help further that relationship.

Moreover, the current wave of antisemitic hatred involves tropes rooted in centuries of Catholic antisemitism. As an Italian Jew living in a predominantly Catholic country, I have seen this firsthand, such as images of a crucified Jesus used as a metaphor for the supposed plight of the Palestinians and Hamas. Together with statements like Gallagher’s, this puts the future of Catholic-Jewish dialogue in question.

On Oct. 27, Pope Francis issued a prayer for peace that also failed to condemn Hamas and its atrocities. As Chief Rabbi of Rome Riccardo Di Segni rightly stated in the Italian newspaper La Repubblica on the same day, “Prayer is a weapon even if it does not shoot and its morality depends on its content. It is good to see multitudes gathering to ask for peace, looking beyond the terms of conflicts, wanting an end to suffering, but one must consider whether looking beyond does not mean flattening differences and making everyone equal; in every conflict there are not all the good guys on one side and all the bad guys on the other, but certainly there are those who are better and those who are worse. Prayer can become an alibi for unburdening one’s conscience, for establishing inappropriate equidistance, for erasing moral evaluations.”

Despite Francis’s problematic conduct, however, there are some courageous Catholic voices that have unequivocally condemned Hamas and expressed solidarity with Israel.

For example, the Vatican’s Secretary of State Cardinal Pietro Parolin stated in the Vatican newspaper L’Osservatore Romano that Hamas’s attack was “inhuman” and “it is the right of those who are attacked to defend themselves.”

Similarly, on Oct. 11, Archbishop of Boston Sean O’Malley said, “This act of aggression requires a clear condemnation in human, moral and legal terms. Both the purpose of the attack and its barbaric methods are devoid of moral or legal justification. There is no room for moral ambiguity on this issue. Resisting such terrorism and aggression is the moral duty of states to be carried out within moral limits.”

The Vatican should listen carefully to O’Malley and Parolin, because not just its relationship with the Arab world and other political considerations are at stake. The Vatican’s reaction to the Oct. 7 massacre and its aftermath will play a decisive role in the future of Catholic-Jewish dialogue. If it continues to maintain its ambiguous position, the Holy See risks its entire relationship with Israel and world Jewry.

Sadly reminiscent of Pius 12th’s moral failings during WW2. Whilst I can understand that Francis is conflicted regarding his Arab Palestinian co-religionists, to not call out Hamas’s evil is unconscionable.