Israel and the United States remain at an impasse about American plans to reopen the U.S. consulate on Agron Road in downtown Jerusalem that was closed under former President Donald Trump.

The Biden administration and U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken have consistently touted their hopes of reviving America’s relationship with the Palestinian Authority, which as part of its demands is calling for the consulate’s reopening.

This week, both Israeli Prime Minister Naftali Bennett and Foreign Minister Yair Lapid said at a press conference that they were not willing to entertain the idea.

With the two allies having set out their positions, experts say a cautious game of chicken has ensued to see whose political situation will allow compromise.

‘Reluctant to jeopardize stability of Israeli government’

Experts who spoke to JNS said it would be difficult for the United States to try to unilaterally reopen the consulate without Israel’s permission.

According to Eugene Kontorovich, professor of law and director of the Center for Middle East and International Law at the Antonin Scalia Law School at George Mason University, opening a consulate without the permission of the host government is not consistent with international law.

“By locating a diplomatic mission to Palestinians in Jerusalem, [the United States] is quite clearly doing this to ratify Palestinian claims to Jerusalem,” he said. “So they shouldn’t be surprised that Israel can’t do that.”

Both the Biden administration and the Bennett government have an interest in keeping Israel’s coalition government in power and avoiding any public spats, concerned that the improper handling of the situation can break up the government and bring back former Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to power.

A poll of Israelis released in August indicated more than 70 percent of Israelis were opposed to the consulate reopening.

In the U.S., Republicans have supported the Israeli position and have called on the Biden administration to uphold the Jerusalem Embassy Act. Earlier this month, a letter from 200 Republican members of Congress urging the U.S. State Department to change course appears to have fallen on deaf ears within the administration.

Shira Efron, Israel Policy Forum policy advisor, RAND Corporation’s special adviser on Israel, told JNS that there are some experts in the United States advising the State Department to explore ways to open the consulate unilaterally despite Israeli opposition as a way of creating its “own facts on the ground,” with Israel then reluctantly offering visas and security but not “rolling out the red carpet,” and so avoiding getting into a public dispute with Washington.

“But I think they are reluctant to do that and jeopardize the stability of Israeli government and therefore are looking for ways to do it with consent, compensating Israel,” said Efron.

She said that there is no urgency in reopening the consulate, as the P.A. had previously held reopening the consulate as a prerequisite to restoring ties. But it appears to no longer be a prerequisite as American and P.A. officials now communicate regularly.

The United States has already shown patience on the issue, keeping relatively quiet until the new government was able to pass a budget last week and further stabilize its hold on power.

According to Efron, the United States cannot and does not want to reopen its consulate without Israeli consent, and as Israel is warning of dire consequences, the Biden administration will likely look at ways to reassure the Israelis to get the reopening approved.

A Jerusalem location for the consulate is a critical point of tension, as the P.A.—offended by Trump’s recognition of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital—will not accept any other location.

“The idea is to reverse some of the steps taken by the Trump administration and go back to traditional U.S. policy that the fate of Jerusalem would be decided in negotiations,” said Efron.

‘A place to confirm Abbas’s claims to Jerusalem’

Deputy Secretary of State for Management and Resources Matt McKeon confirmed in a hearing of the House Foreign Affairs Committee on Nov. 4 that the administration is, indeed, seeking to reopen the consulate in its original location.

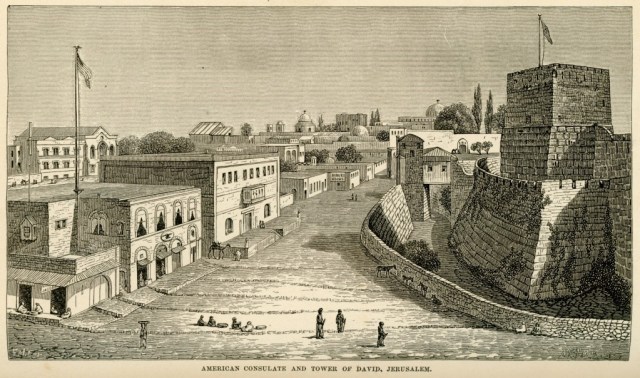

The location is the historic home of the U.S. consulate to Jerusalem, which first opened in 1844. At the time, the area was part of the Ottoman Empire and was grandfathered when Israel was created in 1948 without having to seek permission. Under Trump, the building’s consulate status was removed, and it was made into a Palestinian Affairs Unit under the purview of the new U.S. embassy to Israel in Jerusalem.

Kontorovich said the consulate would specifically be ratifying the P.A.’s claim to Jerusalem. “They’re not looking for a place to talk to [P.A. leader Mahmoud] Abbas; they’re looking for a place to confirm Abbas’s claims to Jerusalem,” he said.

In fact, the Palestinians have been quite open about why they are demanding that the consulate remain in Jerusalem.

“The message from this [Biden] administration is that Jerusalem isn’t one city and that the U.S. administration does not recognize the annexation of Arab Jerusalem by the Israeli side,” P.A. Prime Minister Mohammed Shtayyeh said on Sept. 14, adding that the P.A. viewed the consulate as “the seed of a U.S. embassy in the state of Palestine.”

Ghaith al-Omari, a former Palestinian negotiator and senior fellow at the Washington Institute, said there will have to be a political resolution to the disagreement since one nation can’t put a diplomatic office in another country’s sovereign territory without its permission, and the United States never agreed on the final borders of Jerusalem.

Even when Trump recognized Jerusalem as Israel’s capital in 2017 and moved the U.S. embassy to Jerusalem from Tel Aviv in May 2018, it did not recognize Israel’s definition of Jerusalem’s borders.

The recognition of Jerusalem by Trump’s administration left the borders of Jerusalem as an issue to be decided on through negotiations. That administration’s Mideast peace plan also outlined that the Palestinians would have a capital in eastern Jerusalem, though apportioned only parts of the suburbs, which al-Omari said would not be acceptable for the Palestinians.

“So the principal has been consistent in U.S. positions even under Trump that the Palestinians could have a capital somewhere in East Jerusalem, the question is where,” said Al-Omari.

“There’s a game of chicken, as I see it. To me, it boils down to, does Israel want to make this into a crisis?” posed al-Omari. “What I’m picking up from Israel these days is that they are really trying to kind of take a step back. The Bennett government has been trying as much as it can to avoid public disagreements with the United States. So my sense—what I’m taking from Israel these days—is that they’re trying to look for a creative solution. What that would look like I don’t know, but this is the mindset these days.”

While McKeon did not offer in his testimony that the United States was looking at any other locations besides the Agron Road building, al-Omari believes that they could change tack and find a location in eastern Jerusalem that can be acceptable to both Israelis and Palestinians, but especially the Israelis.

“They have to weigh their own domestic politics—meaning, is this going to be the issue that the coalition would splinter over? The domestic political price versus the kind of diplomatic price of getting into a major crisis with the United States,” said al-Omari. “I think the main weapon, as it were, is the fact that the current Israeli government has really been going out of its way to avoid public disagreements with this administration. This is one of the ways that Bennett is distinguishing himself from Netanyahu—trying to regain the bipartisan support in the U.S. which suffered during Obama and certainly during Trump.”