Five hundred rivets—that was Oskar Jakob’s goal. Failure to meet the quota in a 12-hour shift meant severe punishment.

“If I didn’t make the minimum, I got beaten,” he said.

Jakob, 94, is a Jewish resident of St. Louis and a Holocaust survivor. In 1945, he was a prisoner at the Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp. He was 14 years old and forced to work in a German munitions plant, making rivets used to build the V-1 flying bomb.

Jakob has shared his story previously, but on Thursday, May 16, he will sit alongside the granddaughter of one of the designers of the V-1 bomb and discuss their shared history. The event at the St. Louis Kaplan Feldman Holocaust Museum is a rare conversation between a Holocaust survivor and a descendant of a Nazi scientist. It’s also an opportunity for forgiveness, understanding and hope.

The ‘Doodle Bug’

The V-1 (Vengeance Weapon One) was the world’s first cruise missile. It was powered by a single, noisy jet engine. Allied forces nicknamed it the “Doodle Bug.” From June 1944 to March 1945, Germany launched 20,000 V-1s at British targets.

Robert Lusser was one of the German engineers who helped design the V-1. In 1937, Lusser became a university professor. In return for the appointment, he had to join the Nazi Party. He was a brilliant aeronautical engineer. After World War II, he was brought to the United States, where he worked for the Navy and Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

Searching for answers

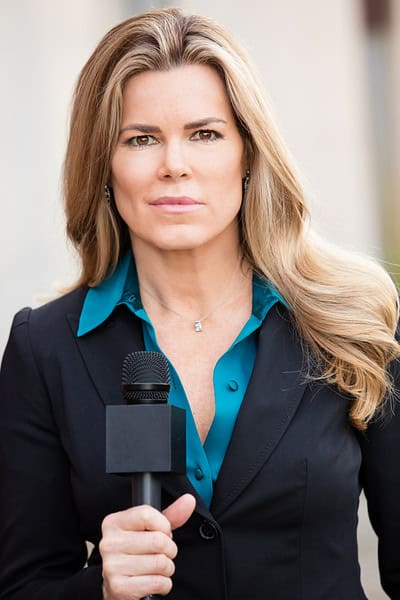

Suzanne Rico is an actress and journalist. On the HBO series “True Blood,” she played a fictionalized version of herself as a TV anchor. Offscreen, Rico is inquisitive and intent on finding answers. For years, she tried to learn more about Robert Lusser, but her mother would only volunteer that he “was a genius.” That didn’t satisfy her curiosity.

“As I got deeper, I discovered the connection to the Holocaust, which was that my grandfather’s bombs were made in this underground concentration camp at Mittelbau-Dora,” said Rico. “There was an incredible, painful realization of the cost, and the concentration camp prisoners who had died by the thousands making these bombs.

“I felt it was important to have a dialogue between me and someone who had been there,” she said. “Nobody wanted to put me—the granddaughter of the creator of the V1 flying bomb—together with a Holocaust survivor and somebody who had been at Mittelbau-Dora.”

The apology

After three years of searching, Rico learned of Oskar Jakob. A trip to St. Louis was arranged and they met face to face. At first, Jakob was dubious about her motives. When he was convinced she was sincere, he didn’t know how much intelligence he had to offer.

“I was trying to figure out why was she doing this because I really couldn’t give her as much information as she would have liked,” Jakob said. “In the tunnels where we were working, there was all kind of Nazi officers going back and forth and checking. It was a big, big tunnel complex. Nazis and SS officers were all over, and we were not even allowed to look in their faces. When they talked to us, we had to look down on the ground.”

Making rivets for the V-1 flying rocket was exhausting and tedious work. Jakob and the other slave labor workers weren’t fed and the little available water was contaminated. Eventually, he was moved to a concentration camp at Bergen-Belsen. That’s where he was imprisoned when British tanks arrived on April 15, 1945, announcing their liberation.

After learning of her grandfather’s past, Suzanne Rico felt the need to make amends. When she met Jakob, besides gathering information about Mittlebau-Dora, she also wanted to express her sentiments.

“The main thing is that she’s sincere in the things that she’s doing,” Jakob said. “No Germans have ever said, ‘I‘m sorry what happened to your family.’ But she did.”

Never forget

Suzanne Rico said she wants to help create awareness of the horrors of the Holocaust and help more people learn the dangers of hate. That’s why she was eager to participate in the “Conversation Builds Character” event in St. Louis.

“I think this is a way to bring the issues front and center again, and maybe actually make people think,” she said. “Everything that I can do to bring awareness up and get people to think is my way of redemption, right? I can’t redeem my grandfather because he’s dead, but maybe his redemption can be found in me.”

She hopes that the audience members who attend her conversation with Oskar Jakob will walk away with a deeper understanding of why it’s important to capture stories of Holocaust survivors. She also believes that her crossing paths with Jakob was meant to be.

“It almost felt like it was Divine, because the way that Oskar and I connected, the memories he shared and the memories I shared, it flowed, it felt right,” she said. “At the end of that conversation, what happened for me was that all of a sudden, the Holocaust was more than just a story in history to me. All of a sudden, it was personal. And Oskar did that for me, and it’s opened my eyes. What a gift that we can sit down and have a rational, emotional, connective conversation about this era in history that was probably the most destructive the world has ever seen.”

This story originally appeared in the St. Louis Jewish Light.